Earlier this summer I took a sleeper bus from Nha Trang to Sài Gòn , reclining as best I could in those “bed” seats made for people 5’2” and shorter while watching miles of rice paddies, motorbike repair shops, and graveyards roll past. On this Sunday return trip from the beach, our bus hit late-afternoon city traffic, so our driver cranked up the volume on the radio to help make the last stretch of stop-and-go on a twelve-hour bus ride as bearable as possible. The DJs were counting down the week’s top forty requests, and, while a third of the hits were in the vein of traditional Vietnamese songs lamenting lost loves, the majority were American pop imports—Lady Gaga, Justin Bieber, Usher, Kesha, among others. I was struck by the polarity of the tunes and how the flagrantly stereotypical American values (casual sex at clubs, wooing a desired target with diamonds and champagne, etc.) embedded in the lyrics of the Gaga and friends were being imposed upon people who, as I could see through my window on the bus, ride four to a motorbike and wave to the bus that drives through their towns daily but which they will probably never be able to afford to ride themselves.

This is not a diatribe on the globalization of American culture, but just an observation that, on the bus, the older men would sing along with the traditional hits and the younger girls and kids would tap their feet or clap to the Western beats. As a Vietnamese-American traveling in Việt Nam , I wondered if there exists a happy medium stateside for my generation—those of us who grew up listening to the monk’s chants at temple during Tết and the longing croon of cải lủỏng singers, but also to battered cassette tapes of The Ramones, Oingo Boingo, and Run-DMC. So, when I got back to the U.S., still in the throes of love with my family’s home country but also eager to satiate my debilitating cravings for a sauce-laden burrito, I began my search for Vietnamese-American artists who are making music for those of us residing in between these two worlds, making our own. And I found Michael Nhat.

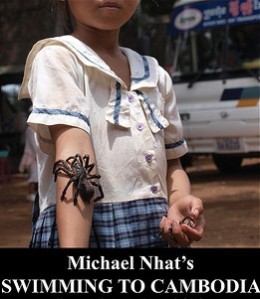

I first listened to Nhat’s self-titled first album while driving from San Diego to Los Angeles. I don’t remember this drive at all. The reason is because I spent that two-hour drive leaning into my steering wheel, an ear cocked to the nearest speaker, confused and fascinated by Nhat’s music, for which I’ve yet to find an appropriate analog in hip-hop, rock, or any other genre of music. His voice is a little raspy, deep, and often breathily urgent; the beats he samples range from cartoonish to dreamlike and lovely in “Ponds and Lakes,” and are punctuated with the inclusion of often humorous voicemails, interviews, or sound bites; his lyrics tackle race and being an outsider, rejection of mainstream hip-hop and club culture, unrequited love and sexual desire, and other things whose purpose or connection aren’t as immediately clear—after all, do you know why werewolves kill or which KKK member raped Bettie Page? Intrigued with Nhat as an artist, I decided to interview him via email on the eve of the release of his second full-length album, Swimming to Cambodia.

In a track titled “Burn Out Your Eyes” on Swimming to Cambodia, Nhat shares—interestingly, via the voice of a guest female singer—the story of his journey from Việt Nam to the United States: “Michael Nhat, originally named Van, was born on November 12th, 1974 in a village outside of Sài Gòn in Việt Nam . There is utterly nothing known about his mother, Minh Nhat, or his father. On April 30, 1975, Van and Minh were in an airplane crash from Việt Nam to San Diego, California. Van was sent to an orphanage in Sài Gòn and adopted by Frank and Beverly.” This autobiographical bit about Nhat’s origins is immediately followed by narration about the first musical recordings he completed. It is through this juxtaposition that it becomes clear Nhat is an artist creating music for generations of Vietnamese-Americans—or any individual, for that matter—who are not or do not want to be defined by the struggle for identity or overburdened by the past, because it is okay, if not important, to express who they are today.

Nhat, though, is certainly aware of the unavoidable struggles of being Asian in America: “Asians like me,” Nhat writes to me, “are the prototype for Asians in the future. We’re the ‘Niggers’ of the Asians, we’re the ‘Gooks’, we do not know how to speak our language, we do not practice or even know any of the culture’s traditions, we get viewed as inferior by Asians who were born into their heritage, e.g. ‘He’s not really Asian he’s white to us!’, and we only speak English. Stripped of our background like African slaves’ descendants, by default, we become ‘Americanized’ and as time goes by, we become more accepted in American Mainstream and begin to see lead parts for Asian males in big budget films that will give younger Asians something to feel proud of and not grow-up seeing themselves as something undesirable with an accent due to an absence of Asians, especially Asian males, in American Culture. We’re currently unmarketable they say.”

Because Nhat creates his art from this space outside of mainstream culture, he also relinquishes the obligation to conform to pre-packaged categories like “hip-hop artist.” In fact, lyrics from “Photos of a Klansman Raping Bettie Page” (yes, not exactly a track for your grade school kids) directly address a renunciation of popular hip-hop radio stations and the label of “rap” in general. When I ask him if his music is a direct response to the über-masculine, misogynist “toot it and boot it” tendencies in mainstream hip-hop, he writes, “I really don’t sit down and write my songs as a ‘Dear Hip-Hop’ letter. Once in [a] blue moon I will write something directly like ‘Don’t Forget to Water the Radio’, but, I think I just allow myself to be myself. A majority of mainstream rap is made by self-obsessed juveniles. I am an educated grown-up, so by default my music will be a far cry from the former. Ninety-nine percent of the time I never take into consideration what mainstream rap’s community will think of me, I don’t even expect them to know I exist and I am absolutely fine with that.”

Ironically, yet fittingly, it seems to be this flying under the radar of mainstream American and hip-hop culture that is granting Nhat a measure of freedom with his art. “No one cares about Michael Nhat right now,” he writes. “Swimming to Cambodia is my White Album. [The Beatles] recorded many pop song albums then did experimental pop and the change didn’t go well with everyone that followed them because of their expectations. I decided to put Swimming to Cambodia out now instead of 5 pop albums later to prove I like, I can and I will make stuff like this, so when I do years from now, fans won’t get upset and say, ‘I don’t like his new stuff it’s too depressing.’ I defeated that.” While Swimming to Cambodia is undeniably Nhat’s style, this sophomore release does feature tracks showing more range in terms of tone—from somber to dancey—and musical influence—the title track sounds inspired by Southeast Asian music, and the opening of “The Spider that Named Himself” is reminiscent of songs from performances of Vietnamese songs at Paris by Night variety shows, while “Throw” samples the 1960s pop hit “My Boyfriend’s Back” by The Angels.

When I ask Nhat if he has any overarching goals in using his experimental album to contribute to music as a whole, he responds, “I do not have a goal in changing music creatively. I have no interest to influence people to write or record anything differently or like me or start a scene which leads a bunch of watered down versions of me. In fact I’d be very upset if people started sounding like me.”

In line with Nhat’s refusal to use his music as a means to enlist listeners as consumers or clones, he says that he approaches the concept of audience openly: “I have noticed my audience ranges from intellectuals to American Apparel models to musicians I look up to like Noh Mercy and even 13 year old girls in Iowa. […] I think I make music for people who want to hear rap they can play it around their 4.0 GPA Art School Grad partner in the car, while shopping for easels and hi-bias blank cassette tapes to record onto on their 4track for their experimental band ‘Hi My Name is Church’ and not feel embarrassed or stupid. There’s a market for advanced thinkers who like ‘hip-hop’ music’s production but could do without the ultra-masculine, he-man, jock turned poet vocals that reigns. I think I am a part of that evolution or maybe not and that’s okay.”

Likewise, when I inquire about whether or not the “you” in many of Swimming to Cambodia’s song titles refer to his audience, Nhat replies, “‘You’ is more often than not, a general setting I treat like we’re conversing on a distorted phone line on Mars while wearing white bed sheets and pretending we’re ghosts. ‘You’ is indeed my audience, my ex-girlfriends, my crush, my parents, my neighbors, my co-workers, my disliked, my oppressor, and my heroes. I can promise you the list goes on.”

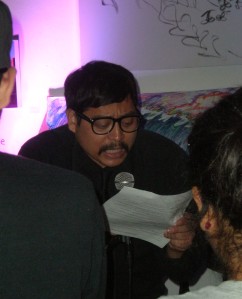

On Wednesday, September 8th, I was able to witness Nhat in action with his audience at his record release party held at Echo Curio in Los Angeles. Prior to his performance, Nhat says, “I do not get nervous before shows. I do not freestyle aka make up crap off the top of my head to prove anything to anyone or make fun of other musicians for sport aka battling. I take myself more seriously than that. I like to watch Joy Division, Little Richard, Jackson 5, Otis Redding, Mick Jagger, and Karen O, to name a few, perform in videos online or at locals shows with bands like Mae Shi, Mika Miko, Health. This inspires me as opposed to Lil Jon or Jay-Z wanna-be standing on stage grabbing their crotch and waving their arms around inarticulately, insincerely and ungracefully making it an uncomfortable bad joke to watch.” And, indeed, Nhat is all business on stage, powering through songs and, at the end of each, thanking the audience, who seems to have created a genuine sense of community (commendable in a world where many indie music events are tainted by a Zoolander-esque feeling of being at an absurdly competitive fashion show) and share an enthusiasm for Nhat. Notable, too, is Lis Bomb’s performance with Nhat. Her singing is clear and sweet, offering a nice complement to Nhat’s voice and indicating that Nhat definitely has a knack for drawing together differing voices and beats to create a sound all his own.

Lis Bomb’s beauty also graces the music videos featured on www.michaelnhat.com, which are simple, yet humorous and oftentimes visually lovely. When I ask Nhat what his level of involvement in this visual aspect of his work is, he writes, “I went to school for film. […] I am very influenced by cinema like Woody Allen, Eric Rohmer, Jean Luc Godard, Robert Bresson, Louis Malle, Pier Pasolini, Kurosawa, Park Chan Wook, and other ‘Boring’ filmmakers most people in Nebraska wouldn’t appreciate because it has subtitles, isn’t famous, or is too cerebral, original and creative for them to grasp, I did say the word ‘most’ not ‘all’, it’s a generalization based on my experience for anyone from there [sic] reading and is appalled by my prejudice. In fact, I take it back there [are] a lot of morons in LA, ever see footage of how these Los Angelinos act after the Lakers win or lose the NBA Finals?”

In regard to the role that Los Angeles—as a city, community, inspiration, etc.—plays in Nhat’s creative process, he makes a meaningful point about how space can stifle or nurture identity: “I was raised in the land of the mediocre and bland [referring to the Midwest], no matter how creative I was, there was nowhere to express it and if there was, I don’t think they would ‘get it’. Instead I’d get laughed at for my authenticity, my race, and non-conservative and non-traditional lifestyle. Los Angeles has inspired me to be myself and not be ashamed of who I am, what I desire and what the meaning of ‘Choosing’ means.”

Keep an eye (and an ear) out for Nhat’s third album, titled Just Plain Dying, to be released on December 21st as one hundred limited edition cassette tapes by I Had an Accident Records. He has also started recording his new album, Insomnia, to be released by Paramanu Recordings in 2011. Until then, you can learn more about Nhat, listen to his work, and view his music videos, at www.michaelnhat.com.

– Jade Hidle

~

Did you like this post? Then please take the time to rate it (above) and share it (below). Ratings for top posts are listed on the sidebar. Sharing (on email, Facebook, etc.) helps spread the word about diaCRITICS. Thanks!