Guest contributor Matt Martin describes and analyzes the works of Phạm Thị Hoài, a Vietnamese writer, editor, and translator living in Germany. Hoài was born in Hải Dương in 1960. In her work, Martin writes, “Anything hinting at the transcendental is fleeting, unappreciated in the moment and mourned with hindsight.”

This post also features the illustrations of Jiny Ung. diaCRITICS is thrilled to have her work grace some of our posts. Jiny Ung specializes in mold-making and animation. She has done production and design work for short films in Southeast Asia. Current animation projects focus on themes of guilt, loss, and queer heroes in the form of fruit-robot-animal hybrids.

[before we begin: like diaCRITICS? why not subscribe? see the options to the right, via feedburner, email, and networked blogs]

__

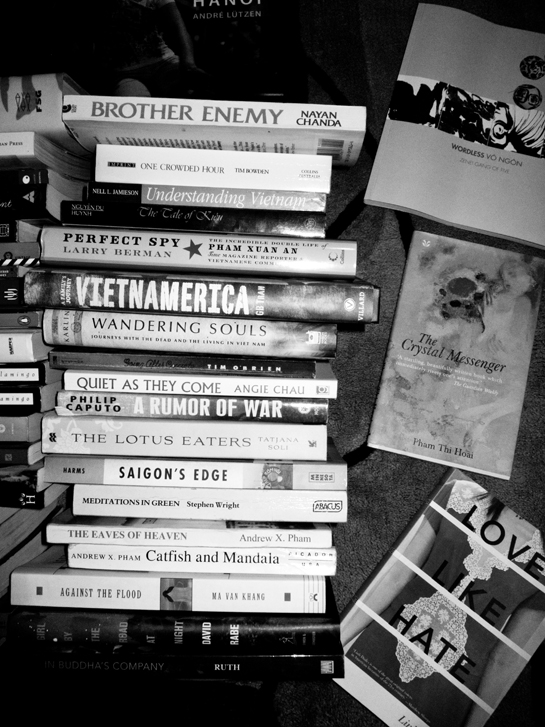

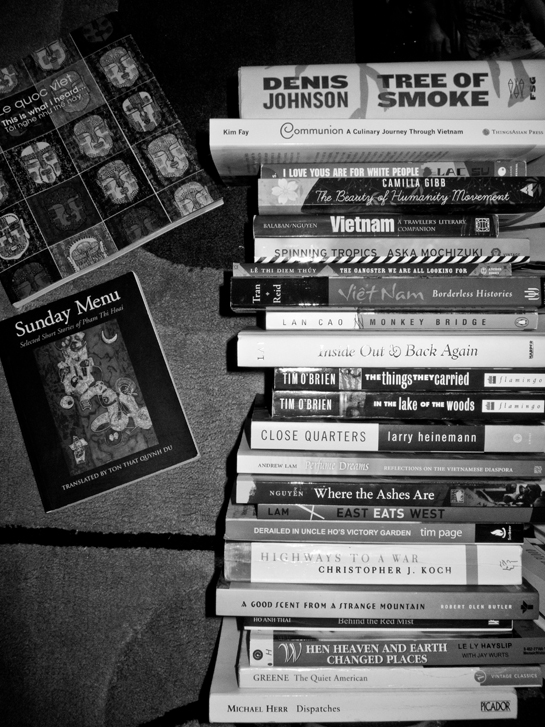

On my last day in Hanoi, at the end of three months travelling over the 2010 new year period, the Vietnamese friends I’d met who could tolerate frustratingly open questions were exploited. I became a recommendation beggar. Many were uncertain about the English translation availability of their favourite authors and poets. Some nominated books I’d already read. Nguyễn Quí Đức, owner of the now re-opened and relocated Tadioto, urged seeking out a collection of short stories by Phạm Thị Hoài.

Had never heard of her. Mostly due to my ignorance, but also because the categories of foreign literature that prove easier to market in English language publishing don’t fit her well. She’s found considerable success in Europe and now lives in Germany (where she’s inspired a film project that intrigues). Her novels and stories were blacklisted by the Vietnamese government but the “political activist” branding—of the Manichean, easily captured in press release kind that can make their industry champions dream of sales, acclaim, and awards—would need to be nailed in askew. She’s not silent on such matters. Not at all. While attempting to make this a little better informed, I was surprised by the quantity and proliferation of her more polemic writing. It just isn’t the defining feature of her fiction. Her purported literary crimes are closer to the ones Hanoi Ink explains led to the recent distribution suspension of illustrator Thành Phong’s Sát Thủ Đaù Mưng Mủ. Ms Hoài’s English translator Tôn-Thất Quỳnh-Du writes in his afterword:

Despite having been attacked in a public forum, Phạm Thị Hoài has never been accused of political dissent [in terms of her novels and short stories]. Instead, her detractors have charged her with holding an ‘excessively pessimistic view’ of Vietnam, of abusing the ‘sacred mission of the writer’, and even of ‘salacious writing’.

Makes for a pretty badass blurb, right? But you can kind of see why it’s Dương Thu Hương who gets the extended consideration from the likes of the New York Times. Those bold declaratives. ”The people have lost the power to react, to reflect, to think”; “a brutal and ignoble regime”; “I fight for democracy”. The laudatory profile of a defiant exile challenging a dictatorial state practically writes itself.

And that’s cool. I’ve finished a couple of her novels. They’re not my thing. I respect them for their role in expanding the audience for Vietnamese literature in translation, and perhaps encouraging the broader industry to take a few extra risks every now and then. Her statements against the Party are valid. It’s not Ms Hương herself who irritates. It’s the facile vision of the kinds of foreign novels deserving coverage, especially those about or involving non-democratic countries, and the lazy angle that coverage inevitably takes. Brendan O’Kane flays (with much more expertise) recent egregious examples relating to the Chinese presence at the London Book Fair.

Ms Hoài is mentioned in a 1994 fragment on the French legacy in Hanoi. Her tribulations are cited as emblematic of communist repression. The only reference to Ms Hoài’s work implies The Crystal Messenger (Thiên Sứ) is straightforward autobiography, presumably because its narrator is also named Hoài. Or maybe the writer thinks Ms Hoài actually did stop ovulating through force of will at age 14 (p. 19). It’s a short travel piece, and yes, I’m being unfair, but if you’re going to throw an author’s name around—an author who hasn’t reached cultural shorthand levels of fame—not including more about what they’ve authored, what the powers that be thought warranted the treatment you’re condemning, feels like a major elision.

Her renown in English isn’t helped by rarely explicitly writing about the French or American wars. In The Crystal Messenger the narrator’s eldest brother is a defector twice over. Her suitor sends her letters literally “from the front” addressed “to the girl at home”. Both nods reveal more about the respective characters than serve as propulsive plot points and otherwise the war is not mentioned. In the collection of short stories entitled Sunday Menu it has less of a presence. Ms Hoài was born in Hải Dương in 1960. She witnessed her share of that horror, as discussed in one of her essays linked to above. You can choose to see the aftermath of cataclysmic trauma in the fractured emotional lives of some of her protagonists, but it’s not nearly overt enough to slide neatly between the borders of enduring preconceptions. Getting a hold of Tôn-Thất Quỳnh-Du’s Thiên Sứ and Sunday Menu translations can be a bit of a bitch. Conversely, Bảo Ninh’s Sorrow of War is deservedly available everywhere, and look at the reception that greeted Karl Marlantes’ Matterhorn, or Denis Johnson’s immersive, sprawling, US National Book Award-winning Tree of Smoke. Contemporary Middle Eastern disasters and a hunger for historical analogies fuel the monomania while the literary Vietnam that isn’t all battles and jungles gets scant recognition outside the academy. And when it’s not wars, the 1.1 billion citizens of the old imperial nemesis to the north usually, and somewhat understandably, devour whatever remains of the English-speaking world’s limited interest.

If eyes did accidentally drift over onto recent Vietnamese publishing, rewards admittedly wouldn’t be guaranteed. Autocratic cultural bureaucracies tend to embrace Sturgeon’s Law like it’s part of their mandate to enforce. A rich untranslated backlog, boundary skirters and taboo benders, and those writing in Vietnamese who through choice or necessity labour on outside the anachronistic infrastructure of control, suffer unduly because of its tarnish. It helps to have someone discerning (no seriously, thanks Đức) to tell you where to look. Vietnam’s pace of change and the echoes of its tumultuous history create the kinds of clashes, contradictions, and dissonance that can be alchemised into gold.

The intra and interpersonal conflicts Ms Hoài chooses to explore mightn’t be typical martial epics but they’re no less compelling or ruthlessly fought. A precis doesn’t really do The Crystal Messenger justice. The portrait of a girl’s adolescence in the shadow of her older twin sister’s monopoly on beauty and tragedy ranges further than such a summary suggests. Sexual awakening, a disastrous teacher-student liaison, gambling duels between a lottery racketeer and Saigon’s ice distribution king, the ambitions of an ideologically punctilious dwarf, an excerpt of stream of consciousness poetry, Machiavellian vengeance, a prison showdown written as a script, voyeurism, literary criticism, diary entries inscribed on an OCD husband’s toilet paper stockpile. Underpinning it all, despite her protestations, is narrator Hoài’s continuing search for a sign lasting happiness can be found in relationships with others. Everything she observes of her parents, siblings, and society upsets her already depressingly unbalanced bifurcation of the Homosapiens-A, who are capable of love, and the Homosapiens-Z, who are not. In the novel’s first few pages Hoài relates her mother’s pointedly repeated regret at marrying her father, the flint and steel for larger domestic conflagrations:

I, the youngest child, the voluntary silent stenographer of the family history, even before learning to read and write, had started to collate these ‘why’ questions into double helixes resonant with the sounds of rain. They twisted around my neck like an uncut umbilical cord, strangling my pubescent dreams, dreams about a harmonious loving couple…

It’s not lugubrious. Much too absorbing and caustically funny for that. Fundamentally I guess the visions of life Ms Hoài presents are sad, but they read human, and very true. Maybe it’s because most characters don’t just sit there passively and take it. Struggle abounds in Ms Hoài’s fiction—the struggle to connect, to sever, to find meaning, to escape into oblivion, to reconcile, to revenge, to forget, to resist desire, to satisfy it, to just get by on the day to day.

The sense of place is strong enough to give a recent reread its share of childish kicks but doesn’t aim for the eidetic or all encompassing. It’s the worlds of the characters rather than some general “Hanoi” that’s vividly captured. I can’t see the “Xanh, Sạch, Đẹp” signs ornamenting bus stops and garbage trucks without thinking of Sunday Menu‘s ruinous “Keep the City Clean and Beautiful” campaign. In In The Rain, a pensive ageing radio jingle singer waits for a date optimistically young in a nondescript cafe she’s chosen and he’s puzzled by. He reflects on the city’s more “famous brown spots”, including “two adjacent cafes near the Thien Quang Lake where customers overflow onto the street…and if you venture in the space in between you would be literally torn to pieces by the rival touts pulling you in opposite directions.” Dismemberment mightn’t be as much of a risk but lakeside rivalries haven’t abated.

The Crystal Messenger is more firmly rooted in a specific era by narrator Hoài’s cutting asides about Soviet authors who never quite made it out of the bloc. Sunday Menu’s stories could be occurring now (absence of technology notwithstanding) or at any time over the last twenty years. Mr Quỳnh-Du highlights Ms Hoai’s refusal to shoulder Vietnamese literature’s traditional didactic responsibility as an unmistakably contemporary aspect of her work. You can’t come away from the stories believing in simple solutions, or relaxing into easy moralising. Certain archetypes that have a tendency to recur across the oeuvre of emigre authors with plenty of good reasons to hate those running things back home never make an appearance—guys like the Loathsome Official Who Encapsulates Everything Wrong With Society for example. In fact, the conceit of “A Traditional Short Story”, the last included in Sunday Menu, is Ms Hoài’s failed attempt at orchestrating “the arranged twists of fate that bring together so many characters, each a symbolic representation of something else.” The system might act as an enabler and an exacerbator but it’s not the fatal flaw vitiating what would be utopia. Ms Hoài’s characters are plenty capable of pettiness and cruelty all on their own.

Purely stylistically, her writing reminds me most of Isaac Babel. George Saunders has remarked on Babel’s simultaneous minimalism and maximalism. Ms Hoài’s is a similar arresting mixture of adroit economy and almost fevered explosions of imagery, sometimes beautiful, sometimes grotesque. It can be intense. She jams a hell of a lot into the two slim volumes I’ve read. In the loneliness of her almost exclusively urban plethora, denizens still inevitably rub up against each other. Hard. The stains and scars of the dirty grind are spotlighted. Bodies creak, sweat, groan, smell, and sag. Sometimes they’re stunted or deformed. At worst they bloat and rot, feeding “a thick black rain of flies”, or are “cut into three sections…clothes a bloodstained dark red.” There are no elegant áo dàied maidens contemplating sunsets over rice paddy. No travel brochure exotica. Anything hinting at the transcendental is fleeting, unappreciated in the moment and mourned with hindsight.

The prominence of often harsh physical realities, or as Mr Quỳnh-Du terms it, “a relentless focus [on] biological needs”, is honest and unmerciful, and part of the reason her writing hasn’t garnered officialdom’s approval. Crowds are tinctured bestial. A weekly public bathing ritual The Crystal Messenger describes leaves narrator Hoài with “a terrifying impression about the fellow members of my species.” Neighbours prepare their “cleansing rite by splashing all the suppressed filth festering inside themselves on the heads of others.” Cyclo driver patrons of the food stall in the story Sunday Menu gorge like a flock of strange birds—”looking in from outside, all you saw was a crowd of people noisily chomping their food and a blur of chopsticks flying from their dipping sauce to their mouths and back again; dipping, licking, dipping.”

As with Babel there’s a relief valve of savage humour. Her satire scythes a wide arc. She offers no glib juxtaposition with the wise or enlightened individual. The most vicious barbs are rarely spoken. They boil away in interior monologues, concentrating the toxicity of future interactions. In Five Days, which charts the unfailingly polite death rattle of a marriage, a husband who hopes an incongruous night of passion could flower into eventual reconciliation awakens to the disappointment of his wife applying her make-up “in the same way sanitation workers spray disinfectants on plague-carrying dead rats.” The decidedly preoccupied narrator of The Toll of the Sea smirks when her leery companion massages her leg, all the while promising his intentions are honourable. She silently reasons “honourable intentions must be when a man touches a woman and the woman does not lose anything, especially her pain.”

Vũ Trọng Phụng’s 1936’s Dumb Luck launched itself at both the ossified traditional order and colonial Hanoi’s bumbling social ladder climbers. Its antihero Red-Haired Xuan exploits the pretensions of his time to rise meteorically and entirely without merit from crude, sex-obsessed tennis ball boy to respected pillar of the community. Ms Hoài’s Vision Impaired riffs a little off that model to skewer an arrogant, ostentatiously “alternative” man—a Vietnamese hipster—and his docile wife. It’s a lewd celebration of the cunning of the street, weighted scales and postprandial price gouging taken to a schadenfreudally righteous extreme. Artists and intellectuals, or at least those who desperately wish to be recognised as such, generally don’t fare well in Ms Hoài’s fiction at all. A playwright in The Toll of the Sea interrupts a pompous lecture on the merits of his latest hackneyed opus to take pervy photographs of the girls sunning themselves along Vung Tau beach. Another story’s narrator jokes “the question that preoccupies our famous artists…is how many wreaths there will be at their funeral.” The Crystal Messenger’s Hoài laughs as, ahead of his daughter’s wedding, her father changes the “criteria for prominence” in his bookshelf “from substance to thickness”.

Decontextualised excerpts like these can sound too pleased with themselves. But the immediate targets of the scorn are almost beside the point; it’s an attack aimed at an especially visible symptom of a more widespread banal evil. So much of the pain inflicted on (and self-inflicted by) Ms Hoài’s characters stems from an emphasis on face and appearances that’s metastasised into a dominating social force. Entire lives are organised according to the imagined expectations and opinions of peers. The ouroboros of rivalry and judgement makes art a cigarette-brand-like badge of status with no inherent meaning or worth, valuable only when flaunted, and ideally envied, pernicious consequences be damned. There’s an unwillingness to publicly call whoever deems themselves artists or writers on their bullshit because everyone else is invested in reputations too. Better to play along and echo consensus than risk incurring a philistine branding. You can always hypocritically snipe in private. As narrator Hoài attends the packed funeral of the city’s literary giant, she wryly notes “nobody of my generation read him, but everybody mentioned him in tones of reverence…his astrology chart was strongest in its ‘slavery sector’”. Her eldest brother Hac’s total devotion to hustling on the basis “numbers had fuck-all to do with culture” almost assumes the gleam of integrity.

The bite and sting of abuse, the dark reflections, the bleak fates and the perpetual struggle—none of it would be such a pleasure to read were it not for the way Ms Hoài captures voice. It’s what makes her great. The Crystal Messenger and all but one of the short stories in Sunday Menu are written in the first person. Narrators range from precocious girls to fading old men without ever sounding forced or inauthentic. I revel in streams of vernacular acid, like that comprising the story Second Hand, because I’m a horrible person, but the eclectic choir also sings with affecting tenderness. Man Nuong is a paean to a love found in decrepitude, mundanity, and imperfection. The same “relentless focus” on biology and mortality that reportedly raises the ire of conservative commentators is harnessed to render a poignancy that’d bury any typical romantic fantasy. Universal Love hits even harder, again because of its pitch perfect tone. In a tiny room on the fifth floor her 16-year-old daughter describes as “a railway station where all the passengers are men”, a 36-year-old woman searches for something ill-defined in a succession of hopeless affairs. Ms Hoài’s precise channeling of that teenager, burned out before her time, innocence sacrificed to serve as the hidden picture to her mother’s emotional Dorian Gray, devastates. There’s no way I can comment on the fidelity of the translations. The day I’m able to study the originals and compare is the day I finish this post in Vietnamese for the sheer joy of showing off. A very, very distant goal. I’m at a level where I can process Hanoi Ink’s great commentary on translating a poem by Bùi Giáng and begin to comprehend how difficult this whole Vietnamese to English thing really is. It’s a reflection on the translator’s thankless task that despite loving both of Ms Hoài’s books, I never properly considered the collaboration that produced them. Writing that relies so much on idiosyncrasies of voice and yet reads so naturally credits Tôn-Thất Quỳnh-Du immensely.

One afternoon, with the family’s single room house to herself, The Crystal Messenger’s Hoài explores her father’s book collection and stumbles across Early Season Longans. The trashy war novel with plenty of violence and one memorably lurid sex scene blows her mind.

There are lucky people whose doors to knowledge are ornate, orthodox, and official, opening onto a shaft of light shining on proper icons. They only need to travel that well-lit path, stand beneath those icons, and they know for certain that somewhere, another door, also ornate, awaits them. My door reeked of dirty sweaty flesh; behind it was mysterious darkness, sinful but irresistible. I do not envy those other doors. I am forever grateful for that most important event in my life, regardless of its questionable worthiness.

I get the impression Phạm Thị Hoài wouldn’t mind dwelling in that mysterious darkness. It’s the domain of her fiction, the truly interesting stuff, the stuff that ends up determining so much of what we do, often mocking our loftier rationalisations. But her writings’ worthiness is without question. She deserves a nudge into brighter corridors. Selfishly, if nothing else, I’m desperate to read more.

__

Matt Martin is currently courting insanity in Hanoi, grappling with Vietnamese at Trường Đại Học Khoa Học Xã Hội và Nhân Văn. He blogs spasmodically at capheinated.wordpress.com and can be found on Twitter @caffeinatedmatt.

Do you enjoy reading diaCRITICS? Then please consider subscribing!

Please take the time to rate this post (above) and share it (below). Ratings for top posts are listed on the sidebar. Sharing (on email, Facebook, etc.) helps spread the word about diaCRITICS. And join the conversation and leave a comment! Have you read Phạm Thị Hoài’s work? What did you think?

Hi, Matthew, I was looking at past e-mails and re-read your comments.

Unfortunately I donot know the books of which you write but your thoughts make me curious and want to read the translations. You wrote a great critique!!

We’re glad to have the piece!

Uh oh. The diaCRITICS have started letting in the riffraff. http://t.co/qBtVZ3Lj