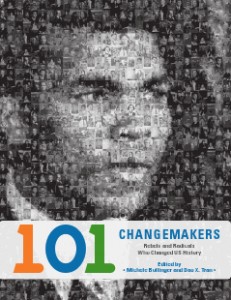

Guest writer Cara Van Le introduces diaCRITICS readers to 101 Changemakers: Rebels and Radicals Who Changed U.S. History. Edited by Dao X. Tran and Michele Bollinger, Changemakers is a handy and interesting take on history via brief profiles on major and, often, minor individuals. Here, Cara Van Le focuses on the profile of Lam Duong as the point of departure for her book review of Changemakers.

[Do you enjoy reading diaCRITICS? Then please consider subscribing! See the options to the above right, via email and RSS]

Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States turned the way we perceive U.S. history on its head by telling America’s past through the eyes of common people rather than by those in power. Could I have read that book as a child? My collection of Babysitter’s Club books tells me maybe not. That’s where 101 Changemakers: Rebels and Radicals Who Changed U.S. History, edited by Dao X. Tran and Michele Bollinger, comes in.

Changemakers acts as a sort of primer into Zinn’s approach to telling history—but for a middle school audience. The textbook gives students a glimpse of 101 people they may have heard about, like Thomas Paine and Frederick Douglass, along with alternative facts on those people. We learn that Rosa Parks, for example, was not an independent agent reacting against oppression after a long day at work, but rather she was an active organizer with the NAACP. We also learn about folks who are written out of mainstream history texts altogether, like slain journalist Lam Duong, who you may be familiar with from Tony Nguyen’s film, Enforcing the Silence (reviewed here in diaCRITICS). A Vietnamese American in a textbook on U.S. history? Yes. (Tony Nguyen, by the way, co-wrote the piece on Duong that appears in the book.)

People of color, LGBT folks, women, youth, and artists—people whose stories my middle school self would have devoured faster than Lunchables boxes because they were reflections of myself and of people I loved—these people are represented in Changemakers, accompanied by resources for further reading and age-appropriate questions that provoke the students, on the whole, to think about issues not discussed in regular, test-oriented curriculum, and to develop critical thinking skills to bring with them when reading other texts.

However, I’d like to go back to Lam Duong’s profile for just a moment. One of the questions at the end asks, “How was Lam different from many other Vietnamese in the United States?” The question seems to encourage students to form opinions of Vietnamese Americans in a communist/anticommunist dichotomy. How do we know that “many other Vietnamese in the United States” weren’t like him? After all, the reason why Changemakers exists in the first place is because these stories aren’t told in textbooks. Unless, of course, the answer to the question is that Lam, unlike many other Vietnamese in the U.S., came to the United States before 1975. But in conjunction with the last question on Duong’s profile—“Is freedom of speech the same in all communities?”—this seems doubtful. While middle school students are capable of applying first amendment issues to many aspects of this book, to answer this question in the context of Duong’s case requires much more nuanced contextualization—What community are we thinking of here? All Vietnamese Americans? All anticommunists? Or just the militant anticommunist group who claimed responsibility for Duong’s murder? Taken together, the questions seem to lead the students too much into thinking of the “rest of” the Vietnamese American community as a conservative group that opposes freedom of speech. While Duong’s story is important, it needs to be placed in a deeper context of Vietnamese American and U.S. history (and, I’ll argue, the role anticommunism plays in U.S. history beyond the War in Vietnam).

In the end, though, it’s unfair for me to hold this book responsible for contextualizing all of Vietnamese American history—and all of U.S. history, for that matter—in just two pages per changemaker. The reason this book tackles so much is because these stories haven’t been made accessible to middle school students. And, in our very flawed public education system, the materials to teach about these issues haven’t been made accessible to the teachers. It’s an excellent starting point for young people to think about and relate to social justice issues. I especially love the interactive ideas in the “More you can do” sections for each changemaker. Students can, for example, take a popular song and change the lyrics to make a protest song, in the style of Paul Robeson. That’s an activity I think even my adult ESL students would enjoy doing, and it would spark conversation about issues that are important to them.

All in all, the book is a good gateway into the social justice community. Changemakers does a great job engaging readers to relate issues of the past to current issues, and to begin to re-think history as it is normally taught. It offers an alternative view of history through the profiles of 101 folks who wanted to see change and found a way to make it happen. It does not represent the only changemakers in American history, but hopefully it will inspire some future ones.

Cara Van Le is an LA-based disorganized organizer of multiple community spaces, an Angry Asian Intern ™, and a food eater/lover/bff. She finished a chapbook not too long ago, with another one or two in the works. She spends her free time writing her ass off and thinks that both black coffee and your stories are amazing.

–

Please take the time to rate this post (above) and share it (below). Ratings for top posts are listed on the sidebar. Sharing (on email, Facebook, etc.) helps spread the word about diaCRITICS. And join the conversation and leave a comment! Who would you add to Changemakers?

I must heartily applaud people whose endeavor is to enlighten the minds of our young learners, particularly their noble attempt in opening the discussion on social justice and people/ethnic history with our Middle School (8th grade to be exact) Vietnamese-American students. I often wonder about those Vietnamese tweens, born and raised in the U.S. and having been fortified with American bovine growth hormones, antibiotics and genetic engineered foodstuffs, do they have the tranquil seriousness to explore the pitfall of such subjects as the killing of Dương Trọng Lâm? Or under the ideal circumstance, would the student regurgitate what s/he has heard from the teacher?

Suspended between bungee jumping and pubescent acne and zits, sometimes plaguing with raging hormones or even suicidal thought, the middle schoolers’ intellectual discussion of such subject usually die in Middle School a premature death.

Having been a long time public school teacher who happened to teach U.S. history in the Oakland Public Schools and SFUSD in the 11th grade, I’ve often felt like a derelict for nor being able to cover the Vietnam War by the end of the second semester, however obsequiously. [U.S. History is divided into 2 semesters, U.S. 1 (from early settlement/Revolutionary War to Civil War); and U.S. 2 (Rise of Industrialization/Capitalism to U.S. on the World stage (Cold War to the present). Any conscientious teacher would feel inadequate if s/he did not prepare his/her students for the History section in the Star test (which supersedes the CTBS), however much s/he likes to cover their pet project, in my case the VN War/American War. Even that, the VN War or diaspora politics, i.e. communist/anticommunist do not usually lend itself to the early college age let alone high school age or Junior high. I often find when discussing Vietnamese VN War or diasporic history that many students (teachers included) are afflicted with ‘a little learning is a dangerous thing’ syndrome.

So in the rush to exuberance and compare 101 Changemakers (by eds. Dao X. Tran and Michelle Bollinger) to Howard Zinn’s ‘A People History of the United States’, I’m curious to know how Cara Van Le makes a jump from her Babysitter’s Club books to such a textbook? Without the benefit of ‘101 Changemakers: Rebels and Radicals Who Changed U.S. History’ in hand, I too wonder how would the editors propose we use this book as a textbook for 8th graders?

101 Changemakers: A Book Review http://t.co/j5MrunCA #aapi #history