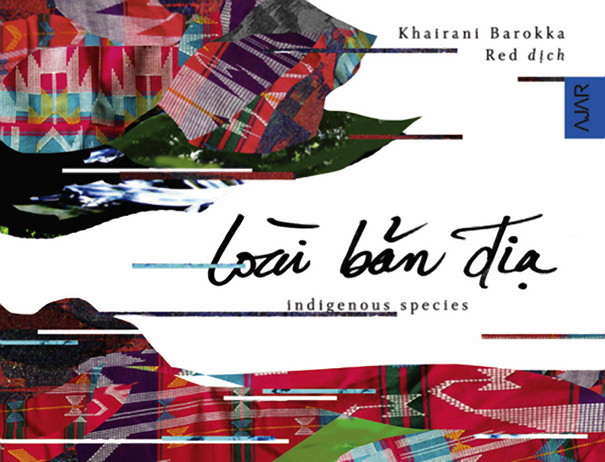

We are honored to publish an essay by Khairani Barokka, on the eve of the Vietnamese language edition release of her poetry + art book, LOÀI BẢN ĐỊA || INDIGENOUS SPECIES, published in Vietnamese by AJAR Press (English version published by Tilted Axis Press). The book will be celebrated in Hanoi on July 14th—look here for the party. And listen in this essay as Okka calls to attention traverses and trespasses of, to, upon bodies, both human/female and geographical/environmental, and draws precarious lines connecting points of toxicity and “unrest” in different nation-bodies (Indonesia, Vietnam) of Southeast Asia.

Our histories, as humans, are of mass migration and of negotiating our roles as ecosystem members, constantly, continuous. We are all offshoots of negotiations between humankind and landmass, sea swells and survival, dependent on life at large continuing robustly, as we change ourselves and each other. I am currently preparing for the July 14 Hanoi launch of Loài bản địa, the Vietnamese version of my book Indigenous Species (the original out with Tilted Axis Press), translated by Yen Hai (AJAR Press). In doing so, I am reminded that the launch will be, in a sense, a return to ancestral territory for the book’s Indonesian narrator, and thus a reunion. 30,000 years ago, after all, the third of four largest waves of human influx into what is now Indonesia originated from what we now call Vietnam.

It is an important, deeply-appreciated step for funding to go towards translation of an art book by an Indonesian author-illustrator, a book in English with smatterings of unitalicised, untranslated (until the glossary section) Indonesian and Baso Minang, into Vietnamese language. While growing up in Indonesia, we heard more about the Eiffel Tower than Angkor Wat, and more about Boston than Hanoi—the latter a city more than ten times as populous as the former—so translation projects such as these are an encouraging sign that regional interchange and dialogue matters. I sincerely hope Vietnamese readers will be able to feel for Loài bản địa’s heroine, an Indonesian girl kidnapped and placed on a boat on a rainforest river, that it will remind them of how similar we are, of the struggles we face together, that we are neighbours and not alone.

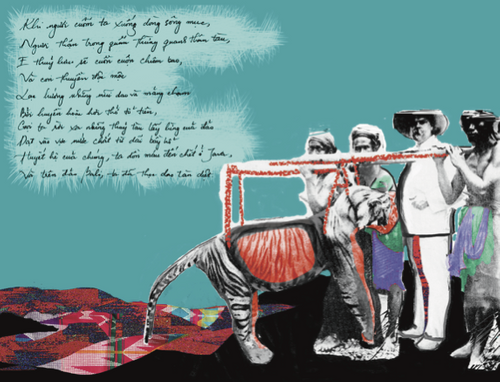

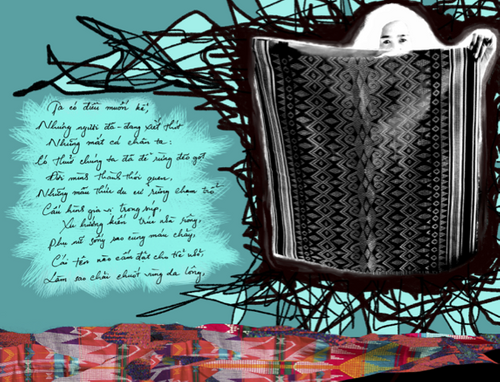

The unnamed heroine of the book is perceptive in her isolation. Her heart is ferocious as it is tender in understanding that the environmental destruction around her is violence against human, animal, and non-animal forms of sentience. As she rallies against social-ecological crisis and plots her escape, she is intensely aware of how far we are from universally caring for our own continuance as a species, of what we must do to entrust ourselves and following generations with liveable futures.

It is deeply meaningful to me to have this story translated into Vietnamese because, though set in Indonesia, it is also a tale familiar to Vietnam: of physical, sexual, emotional violence, particularly against young women, girls, and sexual minorities, compounded if we are also from other groups made vulnerable by structural, historical forces. Economically “lower class” and/or D/deaf and/or disabled and/or an ethnic minority and/or indigenous and/or queer, etc. Both Loài bản địa and Indigenous Species intentionally leave every left hand side of the book mostly blank, with the word “Braille” in Braille written to mark a translation of absence—to highlight how publishing continues to fail millions of blind and sight-impaired readers with inaccessibility. Inaccessibility, like misogyny, like disregard for the environment, is a manufactured product of human agendas. It is a tale of colonialism reaching its tentacles into the present and future, of wars, and, yes, environmental destruction, with D/deaf and/or disabled people much less able in our countries to assert our opinions and rights with regards to it.

Environmental movements in both Indonesia and Vietnam have always been the recipient of violence. Distinct from some white western characterisations of environmental movements as the preservation of a somehow pristine nature, distinct from local inhabitants, there have always been both Vietnamese and Indonesians who understand that with the destruction of the environment comes the oppression of humans. Oppression does not discriminate between old growth rainforest tree and young girl in its philosophy.

There was, as just one recent instance, the sentencing in January of Indonesian activist Heri Budiawan to 10 months’ jail for protesting a gold mine. There was, just as one recent instance, the sentencing in February of Vietnamese activist Hoang Duc Binh to 14 years’ jail, for livestreaming an important protest against Formosa Plastics Group over Facebook. In 2016, the Taiwanese-owned Formosa corporation spilled toxic substances along the Vietnamese coastline in 2016, and fishermen marched to protest the poisoned water, and to file a lawsuit against them. Hoang Duc Binh was sentenced for reporting the truth: these fishermen were stopped and beaten by police.

We are aswamp in toxicities of so many kinds, of legal systems with colonial legacies of compulsory heteronormativity and ablenormativity, that increasingly threaten the rights we have as Indonesians and Vietnamese to be treated with kindness, to have our waters not turned poisonous, to have our air not polluted. In the introduction to Loài bản địa/Indigenous Species, I write of how nearly 100,000 premature deaths were caused by smoke from forest fires in Indonesia in 2015. This smoke knew no national borders, killing adults and children across parts of Southeast Asia with no regard for humankind’s artificial markings of territory. We suffer from the same onslaughts—but just as with our kidnapped heroine in the book, there is a strange freedom in naming unrest, in being unrest, in unrest together.

Visit the AJAR press online store to order Loài Bản Địa || Indigenous Species.

Image credits: book cover and page spreads from Loài Bản Địa (Indigenous Species) by Khairani Barokka, published by AJAR Press, 2018. Poetry + artwork by Khairani Barokka, Vietnamese translation by Red, Vietnamese handwriting by Dan Ni. Used with permission.

CONTRIBUTOR BIO

Khairani Barokka is an Indonesian writer, poet, and artist in London, whose work has been presented extensively in twelve countries. Among her honours, she was an NYU Tisch Departmental Fellow, and is a UNFPA Indonesian Young Leader. Okka is creator of shows such as Eve and Mary Are Having Coffee, co-editor of HEAT: A Southeast Asian Urban Anthology and Stairs and Whispers: D/deaf and Disabled Poets Write Back, author-artist behind Indigenous Species, and author of Rope. Her most recent exhibition is Selected Annahs, on now at SALTS Basel. She is a Visual Cultures PhD Researcher at Goldsmiths.

Khairani Barokka is an Indonesian writer, poet, and artist in London, whose work has been presented extensively in twelve countries. Among her honours, she was an NYU Tisch Departmental Fellow, and is a UNFPA Indonesian Young Leader. Okka is creator of shows such as Eve and Mary Are Having Coffee, co-editor of HEAT: A Southeast Asian Urban Anthology and Stairs and Whispers: D/deaf and Disabled Poets Write Back, author-artist behind Indigenous Species, and author of Rope. Her most recent exhibition is Selected Annahs, on now at SALTS Basel. She is a Visual Cultures PhD Researcher at Goldsmiths.