Isabelle Thuy Pelaud is an academic, a writer, a visual artist, and co-founder (with Viet Thanh Nguyen) of the Diasporic Vietnamese Artists Network (DVAN). Author of this is all i choose to tell: History and Hybridity in Vietnamese-American Literature, the first scholarly work to center Vietnamese American authors, Isabelle has, more often than not, been the one pushing forward the work of other writers and artists, tending and holding space for community, sharing, and networking, while continuing to advocate tirelessly for our diasporic stories to be heard and seen, on their own terms. DVAN’s last decade of activities—spanning numerous literary readings, art exhibits, film festivals, publications (including this blog), panels, community events, and more—were, in many instances, ideas seeded, planned, and orchestrated from around Isabelle’s kitchen table, by Isabelle and Viet and via the grace of many volunteers: a true grassroots, passion-fed, labor of love. As DVAN heads into its second decade—looking toward expansion and becoming more established (perhaps even moving from the kitchen table to an actual office…)—we thought it due time to give its founder, truly the heart and engine of this endeavor, some space to share some of her own stories.

In this intimate interview, Isabelle Thuy Pelaud talks to Vi Khi Nao about everything from poetry, to her childhood in France, to her fight for the lowercase ‘i’ as a form of subversive rebellion, to dreams, to wonderment, to the beauty of anti-theoretical living as learned from her dog Coco.

Isabelle is Executive Director of DVAN. You can learn more about DVAN’s current work and contribute here.

VI KHI NAO: You once wrote a poem printed in an anthology in Australia with the following line: “Our silence is our gift…” Do you feel connected to that vision or choice? And, outside of context, what do you think you meant by that phrase/stanza? If you wish to have a reference to yourself, I pulled that line from a poem you read on YouTube. I love the way you read this poem. It’s quiet, but like a bamboo tree so resilient in its effort to explain the impossibility of the personal fusion between isolation and the unknown.

ISABELLE THUY PELAUD: Yes, i remember. Those words refer to the past. Our silences were our gift…. It refers to my awareness of my Vietnamese mother’s silence as a gift to my French father, something she taught me and something he imposed. These words are meant to create a bridge between my mother and i, as opposed to emphasizing our differences (something i have done as a teenager). These words are also a gesture against the gaze of those around us who associated our silence with stupidity, passivity and weakness. Our silence was a choice. A very small choice, in the sense that speaking was not welcome; but it was a choice nonetheless. Finally these words allude to sacrifice…we were sacrificed to make someone else feel big and strong… and my mother sacrificed our mental health in order to have a roof over our heads and food to eat. The word “gift” has a double-edged meaning… it is a positive act because it is generous; but it is also negative because what is given harms the self. It is not something i advocate… but it was a tool of survival which i look back on with empathy and forgiveness.

You know, as i listen to this poem, i think i changed that last sentence when i read it. i think the written word is different…

VKN: Really? What did you change, Isabelle? What was the original sentence? And why do you think you changed it? Also, in the sentences of your previous paragraph, you typed your first-person singulars in lowercase, “i”—is that intentional? If so, how come?

ITP: i do not remember the written words, i would have to check. But i think i changed it so as to further anchor my desire to find my mother, to connect with her.

You have a good eye for detail. Yes, i have written my name in lowercase. lê thị diễm thúy does this too. It has something to do with resisting the position of authority. My name written in lower-case feels more right to me; at a personal, professional and artistic level. i tried to do this in the publishing arena, but it did not work.

VKN: Would you like to continue to write “i” in the lowercase? In some ways, because the “i” exists in its lowercaseness, it makes us notice its existence more, which I think is sexy. And, in continuation of the above reasoning, which authority or figurehead do you wish to resist?

ITP: Yes. Thank you for noticing. At a personal level, i have a hard time with authority figures. This may be in large part because of my father who could be violent. It also has something to do with my place growing up as a minority. i remember the first time (when i was around 15) i heard someone talk about me with the word “she”. i was startled because i was referred to as a human being. You’ve got to understand, i was mute, invisible until 16 and too visible after 16; i grew up with violence at home and racist bullying at school. At 18, i stuttered. To speak in front of more than one person was so hard. The little “i” honors that young child and teenager who did not know she was a full-fledged human being, on par with the French.

At a professional and artistic level, i have a difficult time seeing myself as an authority for other reasons. Having stayed in school for such a long time, i realized that the more i learned, the more it was clear that i was only hardly touching surfaces and that all knowledge and understanding is constructed and constantly changing. Especially when i took classes in different disciplines… The lack of communication and intellectual engagement between them create large gaps in the production of knowledge.

And finally, it was very hard for me to become a so-called expert in Vietnamese American literature, because I do not speak Vietnamese, i am not a refugee, and i am mixed race. i also never thought i would become a professor, considering my class background. It took me a long time to finally decide to do the work that i do. But i saw a need for it. And although there were no jobs for this expertise at the time, i went ahead with it.

VKN: Perhaps your traumatic experience with stuttering gave you the impetus to create a network of voices for others so that although at times you couldn’t speak for yourself, you could speak for others, outsiders/minorities like yourself: refugees, Vietnamese, diasporic folks, immigrants, etc. Isabelle, was stuttering something you experienced more physically or was there a psychological component to it? If so, did your doctoral studies in Ethnic Studies help shape and hone your literary vocal cords so that you are able to find fluency within the other voice condition/genre itself? What do you think is your primary fluency? What is your opposite of stuttering? Violence not only impacts our verbal language, but I notice that it also impacts our grammatical structures. Whenever I get nervous or excited, my grammar falls apart and I lose my nouns and sometimes my verbs. The only things that seem to retain their stability and clear visibility are pronouns. Do you feel this way too, Isabelle?

ITP: i am very sorry you understand violence, Vi. Yes. My stuttering came from fear of authority figures who abused their power. Stuttering is awful. Thoughts come rushing in, and the words do not follow, which produces anxieties, if not sheer panic. Then nothing comes out right.

i no longer stutter, but i am still uncomfortable with public speaking or speaking to a group.

This week [at Djerassi], we are reflecting on food. Eating at the table with my father was scary. For a long time i could not speak around a table… this makes graduate seminars and department meetings complicated… If it was not for the internet, i could not have done what i have done with DVAN.

In France, in my family and in society, it was not my place to speak. i came to voice through another language with my Vietnamese family. They were warm to me and liked to laugh, and although they were poor, i felt safe with them. When i started to speak English at 19, it was with a Vietnamese accent, because i learned English from them.

My path does not follow a straight line… But it is correct, that i have found in Vietnamese-American literature, stories that i could relate to. And yes, it is much easier to speak and fight for others than myself.

The good part of all of this is that i take nothing for granted. i have grown in a way that i’ve never imagined i would. i am committed to growth regardless of how hard it is. i wonder sometimes if people can tell that speaking in a group is such an effort for me…

VKN: I do see it and it’s noticeable! Your courage and your determined endeavor in the public sphere. Also, your DVAN has opened so many doors for so many Vietnamese! It’s as if you have found a tree for us and we are able to branch out into many different, evanescent leaves, growing and expanding as we avoid lightning or electrical malfunctioning. Thank you so much, Isabelle, for co-creating DVAN! If you had a choice to erase a particular legacy from the diasporic impulse (in general, not just the Vietnamese-American Diaspora) that does not advance the literary, artistic, filmic, performative dimensions of one’s being in the modern world, what would that be?

ITP: Oh Vi. i am tearing up. Thank you.

Vietnamese-American writers do not need me nor Viet to write. Vietnamese-American writers are doing so well. Due to the scope, depth and quality of this body of texts, Vietnamese-American literature is taking a prominent place in Asian-American literature and American literature in general. It is exciting to see. My initial intent when creating DVAN was to create a safe space for writers across national boundaries to write on their/our own terms; i also believe that we are more heard as a group. In the late 90s, when i was writing my doctoral dissertation on Vietnamese American literature, it was clear that Vietnamese-American writers felt pressures to write the refugee experience in a certain way in order to be published in a mainstream press. As Monique Truong said, their stories were used to help a mainstream audience find a resolution about the outcome of the Vietnam War. i agreed with her. All my work has been geared toward denouncing this problem and fixing it in the small capacity that i have. So to answer your question, i would remove that pressure and raise the awareness of the general public about the power of their own gaze and wants in regard to what Vietnamese-American writers and minorities in general produce.

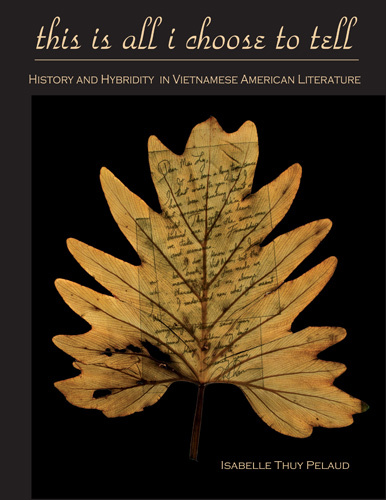

VKN: Thank you, Isabelle, for that thought-provoking response. Speaking about your work, how do you feel about the reception of your scholarly book, this is all i choose to tell: History and Hybridity in Vietnamese American Literature. Were you happy with the response? If not, what kind of responses did you desire from your readers, the publishing industry, and other academic institutions? Suppose you were to write another book with the opposite subject matter: what would you choose not to tell?

ITP: i like your questions. Thank you.

i did not think i could write and publish a book. That this work was published is amazing to me.

The publisher once told me that it was the most-sold book from that press in the Asian-American category. i am not sure if this is still the case. It is quoted by scholars in the field, because it is the first book that centers Vietnamese American literature. i am happy that it helped pave a way.

The title “this is all i choose to tell” comes from a poem from Truong Tran (i was able to fight for the lower case of the title!)…it refers to the expectations writers feel or at least felt a decade ago. It goes something like this: “If I cannot tell what I want to tell in my own terms, I will not tell all. Instead of being acted upon, my selection of what i say within the space i am allocated, is my choice”.

i will not write another academic book. i have done my part. And younger scholars are doing such excellent work.

It is very generous of the DVAN team to encourage me to write, and invite me to read sometimes as a writer. i feel blessed by this unintended turn. All i want to write now are stories and poetry (and grant proposals for DVAN). As i am writing a story inspired by my life, i am now grappling with what i can tell and not tell. What i choose not to tell is, by definition, mine to ponder upon 🙂

VKN: Congratulations, Isabelle, for your accomplishments and also your success in the battle for the lowercase! I am so thrilled for you! What a great game changer! I also love Truong Tran’s poetry very much. He writes as if words would eat each other if they could, one word capable of stepping on the toes of another word; and he makes it seem so beautiful to do so. Shifting away from your scholarly fruits (no puns intended) and onto the other things you wish to do: write your own story. In an interview you said you wanted to be a filmmaker but you didn’t know if you would find financial stability with it; and so you became a scholar before you pursued your artistic desires (poetry, fiction, sculptural installations). In the same interview you said that you felt like you could hide behind the camera. With literary analysis and inquiries which evoke a different kind of vulnerability structure, do you feel that you were able to hide yourself behind the intellectual walls of theoretical and institutional frameworks? Or were there times when your scholarly selves leaked towards the personal? And how did you feel about or cope with those exceptions/excretions?

ITP: Thank you Vi.

Yes, i love Truong’s work for both its form and content. You write about his work beautifully.

i was a student of Trinh T-Minh Ha. i wanted to be a visual anthropologist and turn the gaze of anthropology toward itself, while also documenting people’s lives, denounce injustices, and travel the world, and yes, write stories too. i got accepted at USC, Stanford and Temple University. i did not attend any of these programs because my husband of the time did not want to move or go into debt. i tried to be a good wife, let go of my dreams, and went into a program that was local and free. i went into Ethnic Studies at UCB because the person who recruited me said i could make films there. When i was told i had to write a dissertation and teach, i cried for six hours. i was not afraid of the work, but i was terrified by the idea of talking in front of people.

And yes, Vi, you are thorough with your research; i wanted to collect stories behind a camera because i would not have to talk and i could tell without being seen. In academia, i discovered that i could hide too in a way. Much of the work is done alone in the library or at home behind a computer. The writing is impersonal. A literature professor at UCB told me once that literary criticism is about the one who writes it. This is the reason i wrote a little about my background in the introduction of the book, so that readers could understand that my questions, reasoning and selection of writers came from my particular subjectivity; and make it clear that it is not because the work is presented in the form of a book that it reflects the truth. i hope i made this clear. What is needed is a multitude of interpretations of these stories.

VKN: Yes, you did make it clear. That’s a lot of crying, Isabelle! That is a marathon! I hope it felt good! Now you are more secure financially, you have been preparing yourself for the conversion from analysis to creativity, shifting from academia to art, preparing yourself for luxury and courage: how do you define these two words now? Are you steeped, bathed fully in luxury and courage? If not, what is preventing you from a full immersion?

ITP: About five years ago, my husband came out. We divorced. i lost motivation for a while. This shift from academic to creative writing was made more abrupt due to this crisis. Everything became such an effort; i had a very hard time to get going. It was an opportunity to delve into old wounds. i started to write my story. It took me some time to find my creative voice and not sound like a teacher. To write about my life is not easy because i have to remember the past. i understand when my mother says it is best to forget. But i am committed to this project. i abide by the idea that art possesses healing qualities for the self and for those who receive it. i also feel that that it is what i am supposed to do. When i write creatively, time and space collapse and i experience something akin to a sense of purpose and fulfillment.

It is interesting that you use the word courage. i have been thinking about courage recently as a key ingredient to finding a path out of the narrative that keeps repeating in one’s head when one is traumatized.

As i am beginning to feel secure financially, i am concentrating on loving myself and others. To do this takes courage, yes, but also trust, gentleness, feeling what is felt and catching one’s reaction when faced with a perceived danger. My mother is also getting old. i am helping her financially and am preparing to take care of her when she will no longer be able to do so herself. For this, i have to be strong physically and emotionally. To think about what lies ahead helps me take good care of myself.

When i think of luxury and success, i think of community, travel and the state of wonder. i grew up as an outcast, away from people. This was not all negative. Alienation only came through contact with people. But alone in nature, i developed a sense of wonderment in relation to the beauty of the natural world: that has stayed with me. i feel rich to still have access to this. To feel safe, be part of a community and to be able to travel is a source of wonderment.

VKN: You said over an exciting kitchen in Djerassi that you dream more than you live. What is one of your favorite dreams, Isabelle? Will you re-narrate it for us, so that we readers and enthusiasts of your work can live in your dream too?

ITP: You are so sweet, Vi. Did i say this? What i meant to say is that my dream life is rich and i tend to it. At times the dreams synthesize in poetic form what i feel in my waking state. i strive for my inside life to coincide with my outside life as much as possible. Dreams help me do this. Some aspects of Carl Jung’s views on dreams guide me make sense of them. But ultimately, i lean on my intuition to guess what they mean or more specifically, what they mirror about my emotions. It is a good tool for someone who was taught to repress her emotions to make space for others.

i will share with you a good dream i had about six months after the separation with my husband:

i am skiing down a wide slope. i am feeling good. Soon there are a few rocks showing under the soft snow. i have to pay a little more attention to where i go. The slope slowly narrows. i am now surrounded by bushes up to my waist. The path becomes so narrow there is only room for one person. i have to focus on where i go, make quick turns. i am enjoying the challenge. After a while i arrive at the bank of a large river covered in ice. A friend of mine named Galina, who in my mind can do no wrong because of what i see to be her purity of soul and impeccable sense of ethics, is standing there, leading me to the right with her left arm extended and index finger. My skis turn into ice-skating shoes. i follow her direction and turn right onto the wide river, bordered by a forest. Here again, i skate with wide strokes with joy. My long hair is flowing behind me. The air is crisp and the sun is out. i am happy. Then, slowly, there are some ripples of ice under my feet. Once again, i have to watch where i am going, pay more attention. The ice under my feet is also a little harder, thinner, bumpier. i eventually stop by a small trail going back up to where i started. With shoes now back on my feet, i climb the trail and start the loop all over again. i do this three times. The same story repeats. But each time the ice is a little bumpier, a little thinner. i tell myself that i should stop, but i am having fun and take the risk to take one last ride. On the third time the ice cracks and i fall in the river. i am jolted, afraid at first. But then the water only comes up to my knees and it is not the end of the world. It is only shallow ice water. As i take the trail back to where i came from, i arrive at an intersection. To my right is the loop that i just went on, and to my left is a new trail that i had not seen before. i turn left. it is a dirt trail surrounded by fresh spring grass. The slope is gentle and the trail disappears on the horizon. i do not know where it leads to. i walk toward the unknown. But shortly after i start on this new path, i stop and look back. There is something i need to do first before i go. i walk back. There, standing at the intersection, is a huge bear erect on her back legs, looking straight at me. i walk toward her. Behind her is a cub. i fear for my life. Yet i continue to walk slowly toward her. As i stand in front of her, i think she will kill me. Instead of running away, i reach my arms toward her and give her a hug. To my surprise, she hugs me back. There is something rugged and soft to this embrace. In it, i forget myself. i feel protected, accepted and loved. My entire body relaxes. My breath slows down. i do not worry about the past nor the future. i am utterly present. After this extraordinary moment, i turn around and walk back onto that trail toward the unknown without looking back, carrying with me the memory of the hug of the mother bear. My heart is light. i have no fear of what is to come.

VKN: Yes, you did say it while you were washing a small red bowl. You are on the brink of fearlessness! I have never been hugged by a bear before, not in real life and nor in dream life. What an amazing, amazing dream you had! So corporeal, but also unworldly. I wish I were there to witness it! By the way, who is the bear in your life right now? Also on the animal topic, almost bearlike but not really, can you talk a little about your dog? And have you read theoretical works by Trinh Minh-Ha, or Judith Butler or Foucault, to your dog? Does your dog have a favorite philosopher?

ITP: Coco? i do not read to Coco. [laugh] Coco looks a little like a bear. She is a rescued dog. She was the wildest dog at the shelter: she did not know leash, did not know “come,” and did not know how to be social with other dogs. But after a year, with much patience and love, she has become the best dog in the world. She is with me all the time. She just is. In that way she has something to teach. At this point of my life, i am as interested in being and in awareness, as i am in thinking. Aspects of theorists that resonate with me, such as those you listed, i digested them and they occupy my entire being. That’s where their usefulness and power lie. DVAN is informed by theories. It is theories made into practice (i.e.: agency, self-determination, resistance, centering the margin, voice, decolonizing the mind, multiplicity, difference, third space, deconstruction, etc). The intellectual mind is useful to identify and analyze problems, but it is not our sole intelligence. I like the part in Taoism that says that we also have rational, emotional, ancestral, intuitive and corporeal intelligences. They work in tandem. I try to be aware of them so that one does not take over the others. Coco reminds me to stay in my body and sniff the beauty of the world everyday. [smile]

VKN: Thank you for telling us about gentle Coco, Isabelle, and her lack of theoretical drive. Were you surprised when your husband came out?

ITP: i was shocked by the news. i will not tell you more about this out of respect for him.

But i can tell you another dream i had the week he left, that reflects the impacts of this news. The images of my dreams say more about what happened than any of my reflections.

In this dream, i drive in the small white Citroen my parents had when i was a child, on the Bay Bridge from Berkeley to San Francisco. It is full of traffic. Cars do not move. Somehow, i am able to bypass the cars in front of me and arrive at the scene of the accident that caused the traffic jam. A car is in flames on the right side of the road. i come out of my car and walk towards the flames. It is like i am sleepwalking. Just as i get too dangerously close to the flames, a fireman stops me and tells me to move away from the scene. Startled, i see the fire in front of me, and turn left onto the empty sidewalk. i look over the ramp of the bridge, down at the water. There, i see the shape of the bridge underneath to infinity. But instead of being made of metal and pointed shapes like the bridge on the surface of the water, it is made of enormous ancient boulders the color of tropical fish, covered with light moss. They are yellow, blue, green…i am surprised and in total wonder. Distracted by the beauty of what is underneath me and my new vision of what a bridge looks like, i slowly walk away from the scene of the accident, walking the last third of the bridge alone. The noise of the traffic slowly fades. At the end of the bridge, i see a round building made of wood on my left. i enter it. It has the feel of a church as there are benches and an aisle going toward a stage. But there are no religious symbols in sight. i walk down the aisle with some hesitation. i am not sure i am supposed to be there. Toward the front, on the left, sits an older woman. She turns around, sees me, stands up and walks towards me. She wears an indigo blue shawl around her shoulder. From her emanates kindness and wisdom. As she approaches me, she extends her right hand and says with a knowing smile: “Finally, isabelle. Here you are! What took you so long?!”

i like this dream. It speaks for itself. What i love about it is its relationship with time and space. i see what is under the bridge as something very old, something that has to do with ancestors or past lives, an emotional legacy that i may carry. At a more literal level, it is me finally seeing my husband for who he is. What i thought was, isn’t. i like to think of the woman in the round building as my old self (from this life or the next). She is someone who sees me. Her stance encompasses a full acceptance of who i am. She embraces me with humor, while teasing me for all those turns and all the time that it took for me to see and arrive to myself. Who my husband is, looking back now, is quite clear. One only sees what one wants to see. The dream points to the spiritual as a place of arrival. It rings true to who i am. It is comforting. It evokes a sense of home.

The day after i had this dream, i replayed it in my head in order to remember it. When i arrived at the part where i walk alone on the bridge, i saw how utterly alone i was and will continue to be until the end of this journey. i broke down at this vision.

Five years later, i am no longer afraid to be alone. What i choose to look at now is that round structure i entered.

VKN: I understand, Isabelle. Speaking earlier of nuclear authoritative figures and mother tongue or non-mother tongue: what was your mother like, Isabelle? From the standpoint of anti-literature? Meaning, what was she like as a Vietnamese woman residing in France? What was her first name? She lived in Pierrevert, where you grew up, yes, no? What was it like for her? You’ve said it was isolating for you. It made you feel like an outsider. You were able to exile yourself from your isolated France, the France that once called you “chinetoque”—but where was your mother in the exilic spectrum? Did she find some kind of personal agency for herself? Was she artistic? How did she express herself in the French world? And what was it like to see her, in your youth, not being able to speak French fluently?

ITP: My relationship with my mother is changing and i can now speak about her with empathy. It took some time for me to do this because she was not able to protect me in the way i wanted her to, when i was a child and a teenager; but now i see that she protected me in her own way. We did not become homeless.

My mother was like a prisoner in France. She was thirty years younger than my father and had no formal education. Thanks to a relative of my father’s, she took classes for a few months after she first arrived there and obtained a certificate as an esthetician. She was not allowed the leave the house more than two hours at the time, and then only to buy groceries. My father looked at the watch intently as soon as she left the house. She was not allowed to work outside the house. She had no friends and had no family members living nearby. She had to serve lunch at exactly noon, dinner at exactly seven and go to bed at exactly ten o’clock. She was given a small amount of money once a month for groceries only. She never had money to shop for herself or for me. Our clothes came from donations (she is most resourceful). She lived in the constant fear of being late, of not keeping the house neat enough and of me not mimicking enough the child of his liking. The house was very quiet, hardly anyone came to visit. Music and television were forbidden. And every afternoon, no words could be uttered during his naptime.

And yet, within these constraints, she is the one who took the family out of poverty. Since she could not be outside of the confines of the house, she was able to convince my father to let her work at home. She picks her battles carefully, but once she does, she is relentless and never lets go. For a few years, she opened an esthetician business at home. Although my father eventually forced her to close it, she took the money she’d made to hire someone to break a few walls in the house. The rest of the remodeling she did herself. Thanks to her, each time she sold a house, she made money to buy a bigger house. But this meant that every five years or so, we had to move.

Her dream was to go to the U.S. to be reunited with her family. When i was about eleven years old, she decided that i would go the United States and sponsor her. There i would be successful and take care of her. i knew what my mission was, although she never said it in words. i thought that everything i did was my decision alone, but looking back, i see that everything she planned, happened.

And yes, she is an artist. After i left, she started to paint. She is a talented artist. She is also extremely smart and has a will and resilience of extraordinary dimensions.

+

CONTRIBUTOR BIOS

Vi Khi Nao is the author of Sheep Machine (Black Sun Lit, 2018), Umbilical Hospital (Press 1913, 2017), the short story collection A Brief Alphabet of Torture, which won FC2’s Ronald Sukenick Innovative Fiction Prize in 2016, the novel, Fish in Exile (Coffee House Press, 2016), and the poetry collection, The Old Philosopher, which won the Nightboat Books Prize for Poetry in 2014. Her work includes poetry, fiction, film and cross-genre collaboration. Her stories, poems, and drawings have appeared in NOON, Ploughshares, Black Warrior Review and BOMB, among others; her interviews with writers have appeared in many publications as well. She holds an MFA in fiction from Brown University, where she received the John Hawkes and Feldman Prizes in fiction and the Kim Ann Arstark Memorial Award in poetry. www.vikhinao.com

Isabelle Thuy Pelaud is Professor in Asian American Studies at SF State University. She is the author of this is all i choose to tell: History and Hybridity in Vietnamese American Literature (2010) and co-editor of Troubling Borders: An Anthology of Art and Literature by Southeast Asian Women in the Diaspora (2014). She is the co-founder and Executive Director of the Diasporic Vietnamese Artists Network (DVAN), an organization that promotes Vietnamese cultural productions in the diaspora. www.dvan.org

It was an auspicious/ very lucky day when I happened to hear Viet Thanh Nguyen with Ariel Dorfman on Democracy Now. I was intrigued by Viet Thanh Nguyen and read “The Sympathizer” and learnt about Diacritics which I consider probably the finest website I have encountered. So Isabelle Thuy Pelaud you have begun a helped in creating a site that is both thought provoking, searingly honest, and illuminating.

I try read it when I have a few hours to do so as it is neither glib nor a quick read!

I am from India and have lived in the US for over 45 years. I return to India each year, now with only one sister of 4 alive I go for 4 to 5 months. Each visit ( I am 70) though is marked with “precious friends hid in death’s dateless night”. Yet that is life, messy, full of twists and turns and essentially mysterious.

I loved the photo of your mother Kim Sen Dao and of you.

Thank you is too trite a word, am writing this to tell you how appreciated your work is. It is universal as well as specific and in that too is a mark of its excellence!