From Dao Strom (author of Grass Roof, Tin Roof and The Gentle Order of Girls and Boys):

Dear Friends of diaCRITICS,

I am familiar with the in-between spaces. Born at the tail end – in the wake, essentially – of our last, most famous war, I am one of the lucky population caught by that half-number moniker: the 1.5 generation. Not old enough to claim a valid, substantial stake in the sorrows of that era (“you do not know [this or that reality],” my mother could often say to me); but also not young enough to claim exemption and innocence from said history. I was born in Vietnam, raised in California, have lived in Iowa, Texas, Alaska, and Oregon since; in my work as an artist, too, I am familiar with the in-between spaces – being both a literary fiction writer and a songwriter. I am also a mother, a teacher, have at times been a single mother and struggling artist, together. As an artist, you are already choosing a life in the margins, witness of the world around you, reluctant participant at times; as a person between cultures, parts of you will always be divergent. The Vietnamese persona – as far as I can tell – has also been a hybrid one. But it is as well a fierce and passionate one, resistant and indignant of the many influences feeding into it, proclaiming its own independence and strength, and compartmentalizing, dividing, this or that ideology, time period, this or that group from the purity of this or another group. It is a persona full of contradiction, often un-admitting of its own complicated mythology of violence and (even) self-violence. So perhaps my statement, which is the title of this new work, also harbors some irony. And a hope – to look into and beyond the old mythology, to better harmonize our disparate parts for the future.

‘We Were Meant To Be A Gentle People (East EP)’ is a hybrid music-literary project, a 6-song EP album and a chapbook of prose, poems, and fragments on Viet Nam, as a late-century mythology, a war, a word, an inheritance.

[vimeo 42092057 w=600 h=338]

This project is mostly complete and will be released in 2012 sometime. The nature of the work is unconventional, though, so I am striking out on my own to self-publish and self-release it. In order to do this, I need some help to fund the printing/pressing of the books and CDs. I am using the crowd-funding site Indiegogo to do this – and am relying on this platform also to reach out and build community around the project. Contributors will receive “perks” for their support (including CD & chapbook, special editions, etc), and also my immense, ongoing gratitude.

The easiest way to describe the nature of this project, is simply to share pieces of it. Above is a video featuring music and images from the project, plus (below) links to a FREE SONG DOWNLOAD. An excerpt from the prose of ‘We Were Meant To Be A Gentle People’ follows below and is also downloadable. It is very easy to share, interact, and contribute to this project via Indiegogo or the links below – so please do so! Even if you can’t contribute funds, you can show support for this project by liking the Facebook link, sharing the links and samples, or spreading the word however else you see fit.

‘We Were Meant To Be A Gentle People’ on Indiegogo

FREE SONG DOWNLOAD & .PDF EXCERPT on www.theseaandthemother.com

Follow on Facebook – www.facebook.com/theseaandthemother

Although what I am doing here is largely personal and particular, it is inspired out of a collective experience that I believe can speak to others who tread the same or similar uncertainly-defined territories. If we go far enough into the particular, I believe we will eventually uncover the universal.

Thank you!!

~ dao

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

EXCERPT from ‘We Were Meant To Be A Gentle People’ by Dao Strom | The Sea and The Mother :

Maybe sometime in the near future, we’ll wake up.

There is a story my people don’t tell.

But, in truth, I think we were meant to be a gentle people.

This is the wound I came out of.

This is the wound we came out of.

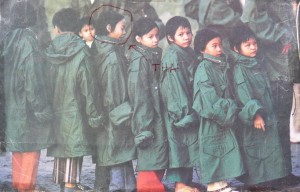

My brother is the boy in the middle of this photograph. It is from 1975, just after the Fall of Saigon, and the photo was taken at Camp Pendleton where we had landed. The photograph appeared in Time magazine, and my mother snipped it and kept it. My brother is the one caught in mid-expression, with his eyes partially closed and his mouth open, as if he were about to speak or yawn just at the moment the picture was snapped. Behind him, there are two boys looking away, looking backwards; we see only the backs of their heads, the oversized bulk of their borrowed green field jackets. The girl in front of my brother looks forward and seems fairly unperturbed, comfortable enough in the jacket that keeps her warm, and we might assume she is the kind who will do fine, she is saavy and adaptable enough, and also she is pretty; we are reassured she will be taken care of. But it is the one in front of her who is the one ((for me)) who begins to give the picture away. This child could be boy or girl with that androgynous long-ish short haircut. And he or she is the only one who appears to notice the camera and is actually looking, with brows slightly furrowed, in the direction of the picture’s shooter. Meanwhile a background of green coat fabric creates an appearance of the children standing in a forest, the foliage of which is made up of more of those same green jackets, but worn by the taller figures of men whose height exceeds the cameraperson’s framing of the shot. These men are very likely the GIs at Camp Pendleton whom my brother says we used to cling to the legs and dangle from the arms of, swinging and playing, like monkeys, in our first weeks and months of life in America.

And how apt it is, the face of my brother in this photograph. The middle boy in line, caught in mid-expression, almost comical, the most hapless-looking of them all. A goof-ball, maybe, we guess. He was a generally cheerful child, sensitive, kind, a boy accustomed to the dynamics of cousins and the care of aunts and grandmother; a boy, who at nine years old, had never known a father. The grandmother is the one he will truly miss, though maybe he doesn’t realize it yet, what with the bustle and chaos of flying and landing and being shuttled here and there and given army-issue jackets to wear and this brand-new ritual of standing in lines, for everything, from food to toilet paper to books he cannot read and clothing that does not fit. For my brother, the exodus struck him at the time as something like an adventure—big airplanes, hundreds of families in tents, American soldiers, treats and toys, games for the children, no school, nothing to do but run around and look for things to do, explore, fight and play with other kids. At Pendleton the boys were in awe of the GIs, comic books, chewing gum, English cuss words. They played pretend-war and cowboys-and-indians. They rolled down sand dunes in the California sunshine. I think the photograph captures my brother’s inhabitance of the moment. He is not questioning or worrying (as the one two heads in front of him seems to be); no, my brother is just caught in it, in the line, in the circumstances of that mid-decade event, in the sheer experience. His eyes are not even open. But his mouth is, almost as if he is gulping it in, life, this, or about to exclaim something about it. This makes you almost want to smile, looking at him, caught half-agape like that. He looks sweet, endearing, innocent. That’s it, I see now as I write it, that is what my brother exemplifies. Innocence. His openness, his haplessness, disarms the viewer. Such hope we have for those children in the photograph in Time magazine in the late spring of 1975. A line of children and each one wearing a different expression or looking off in a different direction. There are so many possibilities, so many ways it can go for each one of them, so much to hope they will receive, discover, accomplish, enjoy. And there is my brother in the middle of the line—in the middle of the composition (the photographer’s inadvertent subtle anchor)—in the middle of expression too, facing forward, mouth ajar, eyes closed. To both directions, eyes closed.

§ I am not in this photograph. But probably I am somewhere nearby, also wearing something green and too large, maybe in the arms of my mother, but also maybe not. (Probably not.) Families looked out for each other, so it’s just as likely some other parent or big sister was carrying me around.

§ I’ve been told, in fact, there were older girls in the camp who chased after me, wanting to hug or hold me. They ran after me calling out my name: Tiêu-Dao, Tiêu-Dao! to which (I am told) I would respond, running away: No Tiêu! No Dao!

§ Alive in me already even then, the wish ((I am all too familiar with by now)) for self-eradication.

§ I was two that year. It was my mother, me, my brother—the unit we traveled as, then.

§ With me: nothing from this period is remembered. I have no memory of the passage we made or the first home I was born to, no shadows or impressions, nothing whatsoever. Any inklings I may claim to have of this period are made up of witness and iconography and documentary and imagination and bias and hearsay and silence and inference.

§ All those memories I may belong to, do not belong to me.

[Pre-order this EP-CHAPBOOK by Dao Strom/support the project at: http://indiegogo.com/gentle-people-ep/]

Dao Strom is the Oregon-based author of the the novel Grass Roof, Tin Roof and the short story collection The Gentle Order of Girls and Boys. She is also a musician with two albums, Everything that Blooms Wrecks Me and Send Me Home. More info here.

–

Do you enjoy reading diaCRITICS? Then please consider subscribing!

Please take the time to rate this post (above) and share it (below). Ratings for top posts are listed on the sidebar. Sharing (on email, Facebook, etc.) helps spread the word about diaCRITICS. And join the conversation and leave a comment!

Quietly beautiful, Strom’s stories are hip without being ironic. Strom’s writing is stunning: powerful yet modulated, impressionistic yet substantial. Her clear ability, combined with the important stories she has to tell, mark her as a force to be reckoned with.