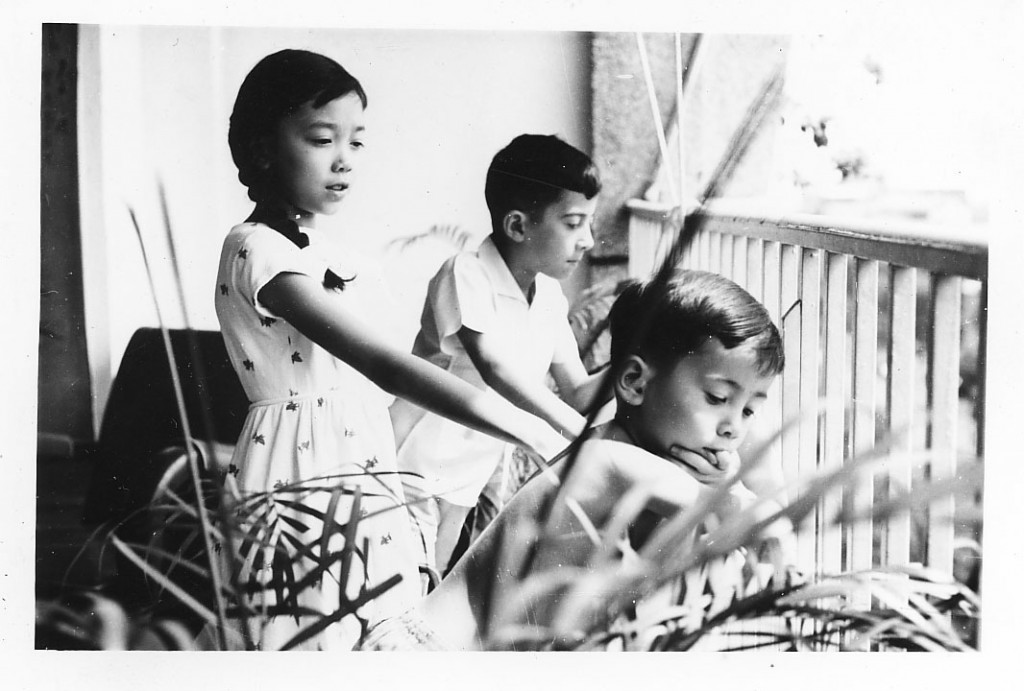

We have an outstanding Vietnamese-French graphic novelist, Marcelino Truong, in our midst. In 1957, Truong was born in the Philippines to a Vietnamese father and French mother. His father served as interpreter for President Ngô Đình Diệm’s English-speaking visitors, while his mother was a housewife who struggled with manic depression. Truong’s memories of his childhood in Viet Nam form the core of his groundbreaking and engrossing graphic novel Une Si Jolie

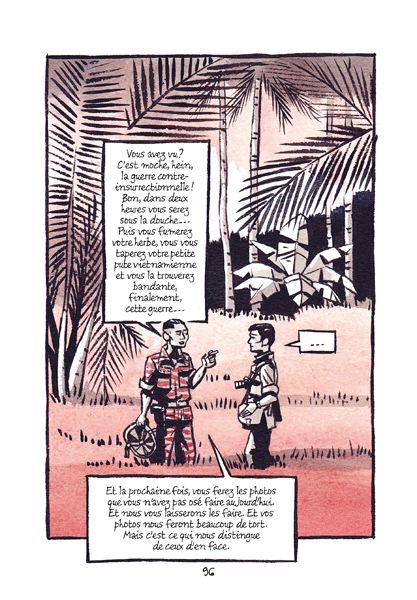

Petite Guerre (Such A Nice Little War), in which the Truong family’s stories are intertwined with the history of Viet Nam in the early 1960s, as twisted policies were implemented by a government motivated by a range of imperatives—nationalism, anticolonialism, and fascination with America. In this graphic novel, Truong focuses on life in Sài Gòn from 1961 to 1963.

Today Truong is a self-taught illustrator, painter, and graphic novelist whose awards include the prestigious Bologna Ragazzi prize. He currently lives and works in Paris. Une Si Jolie Petite Guerre (Such A Nice Little War) was published in October 2012 by Editions Denoël and, for the moment, is only available in French. It can be purchased here, and it is currently under review with several US publishers.

The following is the second post of a two-part article by Ly Lan Dill, who was born in Viet Nam, grew up in the US, and is now a Paris-based translator. The first part ran recently.

[Do you enjoy reading diaCRITICS? Then please consider subscribing! See the options to the above right, via email and RSS]

I met Marcelino Truong in Belleville over a bowl of phở. The ubiquitous scene of phở with its exotic scent of cinnamon and ginger is the cultural marker of an “ethnic” Vietnamese work in the landscape of American literature on diasporas and refugees. A hallmark of Vietnamese-American autobiography, the bowl of soup is often the fulcrum between the personal story set inside and yet apart from the larger national story. The irony of interviewing one of the very few francophone authors of a Vietnamese autobiography over a bowl of phở was perceptible.

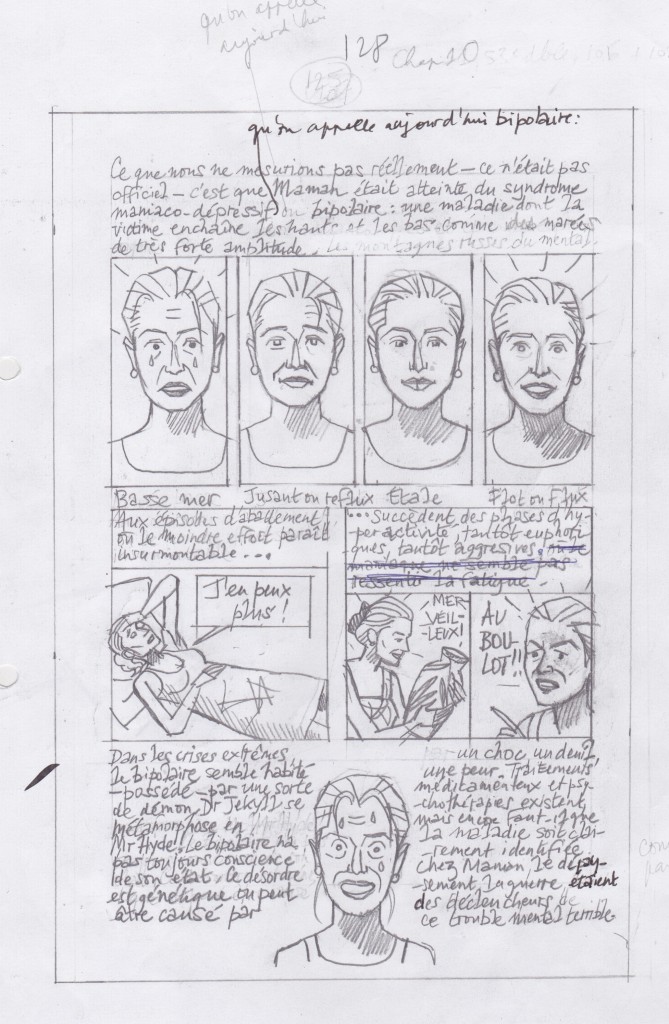

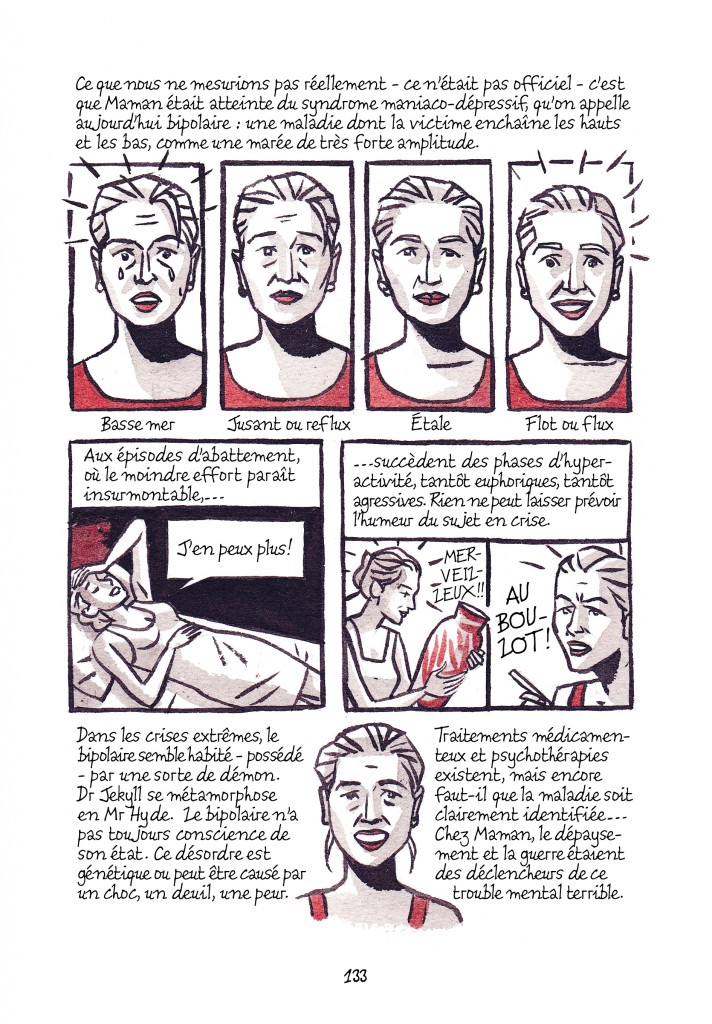

The bowls arrived as we talked of his trilingual childhood in D.C., Sài Gòn, London, of heads of state, diplomats, war, blood, and art. His conversation ranged from his personal work as an illustrator to the TPHCM based Dogma collection of Vietnamese communist war propaganda art. Marcelino talked about his family, his sisters and brother, his parents, his mother. “Some people have said that I was harsh with my mother. This was not my intention. When we were younger, we didn’t have a name for what was going on [her bipolar condition]. We tiptoed around and still things would get out of control. It’s better to say things straight, to call things by their name. It’s easier to bear a situation when you know there was a reason.”

I had been trying to puzzle out why Marcelino Truong’s novel works. The majority of autobiographies situated during the American war in Vietnam have always seemed rather earnest. The balance leans either towards overwhelmingly didactic concerning the historical details of the war (or wars) or deeply personal when depicting family life. Was it the format of a graphic novel? Was it the conciseness due to the genre? Or to the details you can choose to notice in each panel?

As I listened to his stories, it struck me that the answer lay in this honesty, in his desire to say things straight, to find a reason for events that made no sense to a young boy growing up in the 1960s. He could have been talking about the mayhem of family life or about the senseless war. The stakes of losing a nation and the compromise of Agent Orange dovetails seamlessly into losing the appearance of a normal family and enabling the dysfunctions of a parent.

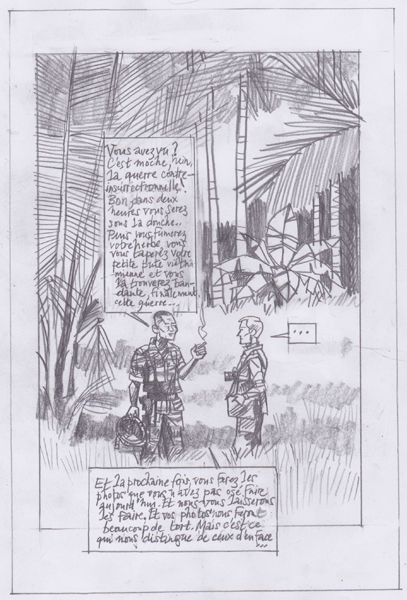

Throughout nearly 300 pages, Marcelino gives each side a fair reading, naming, excavating often awkward truths. His father sidesteps the issue of Agent Orange; but we are privy to his battle to remain a patriot to the end. The Americans are criticized for using obscene amounts of technology; but the choice is framed in an understandable effort to spare their troops. The NLF soldiers are shown as combat hardened enemies with a clear, inspiring goal of “sanctified martyrdom”. They fought for a purpose. Nonetheless, the VNCP errors committed after 1975 are not overlooked.

The very graphic depictions of wartime violence, bombings, and death are defused when seen through the eyes of the Truong children. The horror of their chauffeur, chú Ba, selling his blood to earn money for his family is offset by little Marcelino’s quip that he too wants to sell his blood so he can buy a toy tank. The unimaginable juxtaposition of both worlds forces the reader to accept all sides to every event. The children carry the story forward, in a world of beige, ochre, and brick red. Their red tinged universe is insouciant in its incomprehension of the larger story; they consider both deadly bombings and cricket fights on equal footing.

Their innocence is tempered and framed within panels of steel gray and blue of adult views, film clips, newspaper stories. We are caught up in the unnamed fears of childhood, their helplessness even as our adult hindsight foretells their future against the backdrop of the well-known series of events: the rise of Diệm and his family, military blunders and unrest, Huế, the Buddhist monks, Agent Orange, the American pull-out, the fall of Sài Gòn….

When Marcelino began to talk about wanting to write a graphic novel about the Vietnam war years, both his father and a close uncle – a former undercover agent of the NLF) – shared a typically conservative, Vietnamese stance: “Who could still be interested in these stories?”

The interest lies in the telling of the story. Few fictional accounts have provided the emotional space required to grasp the political complexity and avoid the political cleavages that propelled Vietnam from “such a nice little war” into a war that would not be named. The irony of the title gives the measure of the distance needed to start identifying the chaos and begin to grasp the reasons behind it.

Une si jolie petite guerre—Saigon 1961-63 was published in October by Editions Denoël and, for the moment, is only available in French. However, it is currently under review with several US publishers. Let’s hope Marcelino Truong’s novel will soon be available in English. From his unique perspective as a French Vietnamese with close ties to the US, his reading of the war is one of the fairest, clearest, and most balanced I have read in a very long time.

—

Marcelino Truong was born in 1957 in the Philippines to a Vietnamese father and French mother. He grew up in Washington, D.C., Saigon, and London, where Marcelino attended the French Lycée. Marcelino moved to Paris for his studies and earned degrees in law at Sciences Po and English literature at the Sorbonne, before deciding to become an artist at the late age of 25. He has published in various print media, authored books for all ages, and exhibited his paintings in galleries throughout Europe. The majority of Marcelino’s work deals with Asia, especially Viet Nam.

Ly Lan Dill was born in Viet Nam, grew up in the US, and is now a Paris-based translator. She earned her undergraduate degree in French Literature (Northwestern) and her post-graduate degrees in Vietnamese diaspora literature (Charles V, Paris 8).

__

Please take the time to rate this post (above) and share it (below). Ratings for top posts are listed on the sidebar. Sharing (on email, Facebook, etc.) helps spread the word about diaCRITICS. And join the conversation and leave a comment! If you read French, have you read this? What did you think? If you can’t read French, are you excited to read Marcelino Truong’s graphic novel after it gets translated to English? What sorts of new possibilities are offered by the genre?

very glad to hear it, mbb!

Thanks for writing this 2-part review. I ended up buying a copy from Amazon France and really enjoyed reading this memoir. I hope the author will have an English translation published.

Great review – what about a more liberal translation of the title?

So instead of “Une Si Jolie Petite Guerre (Such A Nice Little War)”, what about “What a Lovely Little War” ?!

I.e. a nod towards the 1961 radio play, 1963 stage play, and 1969 Richard Attenborough movie “Oh! What a Lovely War”? See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oh!_What_a_Lovely_War