diaCRITIC Jade Hidle offers a powerful meditation on history, memory, and imagery, by centering some photos ‘saved’ from destruction in Viet Nam and then purchased, with some ambivalence, in the Pacific Northwest.

Over the holiday break I took a short trip to Portland, Oregon, to visit family and friends. It was the first time I had been to the city since I was a kid, and what little memory I have of that prior trip is limited to fuzzy images of the Rose Garden Arena where, I am told, my family and I saw Hulk Hogan perform his great and glorious wrestling feats. Beyond that, I was returning to the city with fairly fresh eyes. I had been hearing, though, that Portland was the up-and-coming metropole of the Pacific Northwest—touted for its diverse range of cuisine of the booming food cart craze; heralded for its progressive green, eco-friendly recycling and biking movements; and known (whether fondly or critically) as a mecca for twenty-something hipsters sporting skinny jeans, flannel shirts, and knitted beanies pushed back to the crown of their heads just so. Indeed, upon my arrival and subsequent exploration of the city, I found that its different neighborhoods were organized to suit just such a crowd. The main drag of each neighborhood featured a Powell’s satellite book shop, vintage record stores, trading posts for Tibetan arts and crafts, and movie theatres serving pizza and beer.

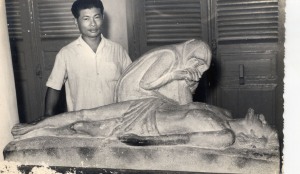

It was on one of these streets that I came across a tiny hole-in-the-wall of a shop that sold an amalgam of randomness culled from the past six or seven decades—from dainty doorknobs to records and books to mannequin heads and packs of Garbage Pail Kids stickers with the dusty, toothache-inducing stick of gum still inside. Among these odds and ends, what was most pertinent to me as a Diacritic was the contents of a little girl’s suitcase from the ‘50s or ‘60s, lined with frilly pink and polka-dotted fabric. It was propped open and from its flimsy gold buckle dangled a handmade starburst of cardboard that read, “Vietnam Photos. $1.00.” And below this, in the bed of the suitcase, two overflowing piles of black-and-white photographs from Viet Nam.

Arrested by the dissonant combination of these items, I stood for a moment or two just staring at this suitcase of Vietnamese photographs for sale. I didn’t expect to see a handwritten price tag combining “Vietnam” and “$1.00” as if the country were in the glass case of a butcher shop, let alone on such a cutesy suitcase better for carrying dolls and footsie pajamas—a valise that probably belonged to a little girl who didn’t even know where Viet Nam was. At least not then.

Curiosity shouldered aside my initial awe and I began to sift through the piles of photographs. Flipping through them, I discovered many scallop-edged studio portraits of women and, judging from the hairstyles, these photos were taken from the ‘40s through the ‘60s. Some looked professional, as though they were publicity shots for singers or actresses. The majority of these portraits, though, were in the style of Glamour Shots or of high school senior yearbook photos—the subjects gazing poetically off to the side or longingly into the sky. I was reminded of my albums of my mother’s school-aged portraits, all embossed with the names of Saigonese photography studios and in which she is never looking at the camera, but always at some deep thought hovering in the distance. When I exhumed this album from a dusty box in the garage and showed it to my mom, she dismissed them, shooing me away with a “kỳ quá!” I smiled at this memory and enjoyed seeing that it seemed so many other adolescents in Saigon had to undergo the primping and awkward posing requisite to these formal portraits.

Then, a pang of sadness hit me, as I wondered how many of these faces had been afforded the opportunity to come to the U.S. and have the luxury my mother had of replacing old Vietnamese photos of herself with American pictures of her, and her U.S.-born children, staring right into the camera with big smiles and the occasional goofy face.

This sadness, this tangling of familiarity and uncertainty, sharpened when I got to the candid photographs. A few capture the streets—fruit vendors on corners, men smoking cigarettes in doorways, and blurs of passing motorbikes. Occasionally, whoever’s camera(s) took these pictures manages to click right as someone smiles, but most of the photos bear stern faces, or the suspicious sideways glance that I think we Vietnamese have perfected to an art. Within this flimsy child’s suitcase, there were so many faces and none of the photographs bore names or dates.

The skin on my arms and neck goosebumped when I came across a photo of a funeral altar, complete with pictures of the dead and smoking incense. I felt a heavy sense of guilt, echoes of my mother’s warnings not to display photos of the dead, especially if you don’t know them. Doing so might inappropriately anchor the person’s soul or, worse, incur some kind of haunting akin to the ghost stories my family told me about their homeland stricken by so much death. I felt guilty just looking at the photo, and then regretting looking at all of the other photos because I assumed the majority of the people in them must be dead now too.

But I still thought they were beautiful. They felt familiar, like home.

I lingered. Debated.

And then, before I could waffle again, I shuffled out the four of the photos that struck me most, limited to only one for each dollar I had left on my shoestring graduate student travel budget. With her sculpted bob and a perfectly fitted jacket, the cashier began ringing me up. As she slipped the photos into a flat brown paper bag, I asked her how so many Vietnamese photographs had been acquired. She first delivered some pretentious spiel about how she usually couldn’t disclose to customers the shop owner’s sources (as if I’m a jewel thief in a Bond film or something), but then, as if a favor or some special treat, she leaned toward me slightly to explain the origins of this particular batch of photos. According to her, the store owner was travelling in Viet Nam on vacation and met a man in Saigon who had a shed full of photos he was going to trash or burn. The shop owner protested, spending hours going through and boxing up the photos that ended up in that pink frilly suitcase. “Isn’t that great?” the cashier asked me.

“Uh, yeah, I guess. It’s just strange,” I said. “See, I’m Vietnamese—” Here the cashier pulls back to her original posture behind the counter, but I continue as if I don’t notice, figuring that she, as do most people when they learn my ethnic background, is merely trying to reconcile the Norwegian features mixed in my Vietnamese face. I continued, “So many of those photos look like pictures of my family.” Now, unless the ceaseless Portland rain had rendered me more ornery than I’d realized, I didn’t say this with contempt or in accusation. Nevertheless, the cashier responded a bit defensively, conceding, “Oh, yes, well. I know. Once a woman came in,” and here she made a subtle, inexplicable gesture that indicated to me the woman in question must have been Vietnamese, “and got very upset that we were selling the pictures.”

“Oh, I’m not—”

The cashier interjected, however cautiously, diplomatically, “I think it’s great that the owner saved all of those pictures. If she hadn’t, they wouldn’t have survived, you know.”

Though I am slightly bothered that her evident guilt manifested in a defensiveness that made me seem volatile, I didn’t bother attempting to return to my explanation that I didn’t ask about the photos’ origins to cause trouble or criticize. I merely thanked her and walked out, tucking the bag of photos under my jacket to protect them from the falling rain.

It is this idea of saving, of rescuing what could have been lost, that feels to me such an American virtue yet simultaneous arrogance. This compulsion to save, and pride in saving, seems to be a conceit of entitlement to trespass not just into another country but into another people’s history. The cashier’s invocation of such terminology echoes for me some of the justifications for the U.S.’s involvement with the war in Viet Nam, not to mention other wars since. Having purchased these photos, I feel critical of such an impulse, yet complicit in it as well. Yet, should this ambivalence spur guilt? After all, my mother herself has used the word “saved” when she talks about coming to America, and the date of her arrival in the States is a somewhat magical number in our family’s history. And is my purchase a saving of a different sort? Will others buying these photos understand and treasure their weight?

So, my feelings vacillate.

On the one hand, I wish the photos had stayed in Viet Nam. If the man who owned them didn’t think much of them, then no one else should get to say that they’re a dollars worth of cute or exotic or quaint or humorous black-and-whiteness, as I imagine many who purchase them are hipsters who get a kick out of what they see as alien Asian faces and tacky hairdos and bad teeth. And a deeper emotional kneejerk reaction made me want the photos to still be in Viet Nam because they are Vietnamese. Like many other second-generation Vietnamese-Americans, I have been instilled with stories of how much has been taken from my mother’s home country and its people. Taking even a discarded old photograph makes me feel the rawness of that wound.

On the other hand, these photos harbor an important power. As an American, I know all too well how Viet Nam and Vietnamese have been visualized in the U.S. From the string of big budget Hollywood films about the war to Nick Ut’s infamous 1972 photograph of a naked nine-year-old Kim Phuc running—mouth agape, arms flailing—from the napalmed village of Trang Bang (her story was later detailed in Denise Chong’s 1999 The Girl in the Picture), Vietnamese have been visually depicted as victims. Marita Sturken, in her book Tangled Memories, presents an accessible and cogent discussion of how this victimology in photos widely disseminated to the American public has served to assuage national guilt about the war and move on, feeling absolved, from the country’s past errors and atrocities.

Beyond this victimology, Vietnamese people are still treated as perpetual foreigners or refugees. I see this when someone speaks to my mother slowly, as if just because she looks Vietnamese (or any kind of Asian, for that matter), she couldn’t possibly know English, as if she must have just gotten off the boat. These slow-talkers don’t consider that my mother, along with so many others in the Vietnamese communities across America, has been in the States coming up on thirty-six years now.

These photos that I found in Portland, then, show different faces of Vietnamese, set in everyday life. America is not a post-racial society, and these photos show that we Vietnamese are people too, as simple as that may sound to some.

How many other photographs are out there, ones that this suitcase could not, must not, contain? Much work, and rightly so, has been dedicated to recovering and restoring the genealogy of the descendants of African-American slaves (I love you, Dr. Henry Louis Gates!), and similar projects are warranted for Vietnamese-American communities. Our paper trail has been destroyed much more recently. Birthdays of survivors are often approximations, while countless faces, names, memories, and histories have been lost.

Now I have these photos, along with my lingering ambivalence about them.

Until I find a (more permanent) home for them, I share these photos and my story here in hopes that, in them, you will recognize the sweet sadness of meeting strangers so familiar.

~ diaCRITIC Jade Hidle is a doctoral student in the Department of Literature at UC San Diego

Did you like this post? Then please take the time to rate it (above) and share it (below). Ratings for top posts are listed on the sidebar. Sharing (on email, Facebook, etc.) helps spread the word about diaCRITICS. Thanks!

Dear Jade, thank you for sharing your thoughts and insights (as well as some of the photographs)!

I think you raise some fascinating and important points, and your text and the responses reveal layers of conflict that still exist in terms of remembrance and the traumas of war and relocation. Of course any act of removing something from one country and taking it to another country by .. a tourist…with the intention of resale… can be labelled cultural appropriation or colonial reflex.

But at the same time, the US as a country of migrants has its own special tradition of collecting and archiving the past (albeit selective) that I appreciate. The impression I have, from the extensive research my father conducted on our own family, is that genealogical research is much more developed here than in other older countries where histories go back so far they are taken for granted, or where the preservation of paper things were just not considered that important. Funnily, the more recently immigrated parts of our family tended not to have saved letters and photographs as did those who came in the 1800s.

Now in the digital age that will all change. It will be a lot harder for curious minds to discover random family photos and muse about their hints of intimacy when most sources are password protected…

– liesl

Wow, you are way too nice. 🙂

Anyway, what that shop owner was practicing is Cultural Appropriation. People try to shelve it off as ‘cultural mixing’ but it’s just profiteering off of other folk’s lives, histories, their pain. It happens a lot but that doesn’t mean it’s right. Thanks for the lovely write up. I loved Portland when I lived there but looking back, I’m glad I’m gone…I just miss my mountains <3

Julie, thank you for the comment on cultural appropriation. Indeed!

Thank you so much for all of your insightful, thought-provoking, honest, and supportive feedback. I believe that by having this dialogue we begin to enact processes of rememberance that the people in these photographs deserve. Thank you again for your time in reading and responding.

Great work. The photos are a springboard to some good meditations. However, as a person who frequents flea markets, I can say that old photographs are quite common. The going rate in those venues are 25 cents to a dollar…so in a retail establishment, a buck is what you might expect to pay. Paper is actually one of the things that you can pick up on the cheap at any estate sale…

My guess is that, if these images were being burned, this has more to do with the way paper is used in commemorative practice. Burning of paper money and sacral images is crucial to ancestor worship…so the actual violence comes in this act of “rescue” but this violence is both a function of the party who did not complete the burning and the owner of the shop who “saved” the images. Some images are not meant to be salvaged.

Jade,

First, thank you for writing and sharing this–I love how YOUR voice is so present in the mingling of what is both”creative” and”critical,” and how you really weave both together your article. You inspire/encourage me to get off my lazy ass and start writing creatively again, or at least be attuned to not letting my voice get lost in my critical work.

Thinking about “saving” and “home” and how the white patriarchal nationalistic history of the U.S. has shaped so many events to their choosing, literally and materially and psychologically altering the lives and histories of non-dominant or non-white subjects is so illustrated in your depiction of suitcase and of the interaction with the saleswoman (among so many other small moments, damn girl!). The “ambivalence” you describe really spoke to me. Just this ripping apart and sewing back together of (hi)stories where there isn’t a clear answer, but there is a new, another story, or another layer to the story that alters the whole framing of the lens, the decision on what to “save” in display…

I’m still thinking about it all–so thank you for that 🙂

My first reaction was bit angry because i felt that a part of my culture/ historical things were selling, and people made profits on this things, especially whoever bough these pictures across the country. I guess i have these feeling because I am Vietnamese woman. I just wanted to tell the owner ” please let these pictures were burned in Vietnam” but don’t sell like that. I feel a bit hurt because those pictures were similar like my mom pictures. A Vietnamese woman was in the traditional long dress. I was also in the traditional long dress in my high school years. I could not believe this things/ business that can happen in here, especially Oregon. Yes, We , our family, are refugees who denied the Communist government. I am lucky and am so thankful to be here. I appreciate that Americans accepted and gave us a home, but I still don’t like people selling our traditional values like that… I wonder what if someone is walking on the street and found out that his/her mom, dad and or sister’s portraits are selling only $1.00, what are their feeling? About the Vietnamese cashier , Gosh i wish why isn’t she die or burn in the hell … I wish one of her mom, grandma, great grandma in those pictures. I wonder how much the owner has made from selling Vietnamese photographs/ from selling us??? $100, yes! $1000 maybe ! $ 10, 000 I doubt of it… So Please stop selling us !

Those photos are excellent, and your description of Portland spot-on. As for the ambivalence, I imagine you are doomed/blessed to feel that way about most things in life as you come from two cultures. “Blessed” because your varied background allows you to hone in, focus, and consider the meeting of two cultures from a very intimate view. Shoot, ya shoulda been an anthropologist.

Outstanding article! Your use of imagery really helps me picture the conversation between you and the cashier. I feel curiosity as well, when I look at the pictures, wondering about the stories behind the people. Great job, once again.

Yep. Historically, white people (I am white) have made money off of the things they have brought “home” from lands south of the equator. This is often referred to as “preserving” cultural artifact, not as plundering. Intersect this then with hip, “shabby chic” culture that Portland pulls off well (I visit a couple of times a year) and what you’ll probably get a weird amalgam of guilt and privilege. And yep, you are probably right in interpreting the shopkeep’s behavior as defensiveness reflecting feelings of guilt. Justification, that’s the work I keep thinking of. Thanks for your candid reflections