Author and songwriter Dao Strom reviews Anguli Ma: A Gothic Tale by Chi Vu and finds the novella raises some troubling questions: is it possible for people who have experienced and perpetrated extreme violence to find peace? Why, in stories about Vietnam, are there so many women among those who cannot?

________________________________________________________________

before we begin: like diaCRITICS? why not subscribe?

see the options to the right, via feedburner, email, and networked blogs

________________________________________________________________

“His fingers are arranged into beautiful mudras… In the sunlight, he stares at his hands which faintly remember blood.”

The central characters in Chi Vu’s Anguli Ma: A Gothic Tale (Giromondo Publishing, 2012) wrestle with the dark emotions that underlie and ultimately beget violence—fear, bitterness, suspicion, alienation, displacement, desperation. While the traumas of their previous lifetimes of war and the exodus of 1975 only glint in the background of this short novel, it is a background that knowing readers will likely draw from in order to understand these characters: they are all still refugees, Vietnamese in a new-to-them Western world (1980s suburban Melbourne, Australia), vying at varying degrees of survival, adaptation, and a sense of security which is largely given to or taken from them (false or veritable as the measure may be) through the acquisition, hoarding, or loss of their money.

There is a very dark figure at the center of this tale: Anguli Ma, the mysterious boarder of Dao, an elderly landlady whose house is divided up and shared only by other women tenants, one young, one old—until the arrival of Anguli Ma, that is. Anguli Ma makes a fair enough first impression, then quickly reveals himself to be a shady entity. He carries home plastic bags of meat, leaves bowls of putrid offal (we don’t know exactly what it is) rotting in the garage, and neglects to pay his share of the rent, eventually robbing the landlady. There are also allusions of connection between Anguli Ma’s violent tendencies and the disappearance of the young woman tenant. Through the eyes of the elderly Dao, we cannot but view Anguli Ma as a malevolent, volatile, threatening figure. However, the larger framework of the narrative posits another question: whether or not a killer—a person with an egregious history of violence; a man who has made a necklace of his victims’ fingers—can become (due the guidance of an enigmatic “monk” he encounters in the park) an enlightened and ultimately peaceful, non-violent being.

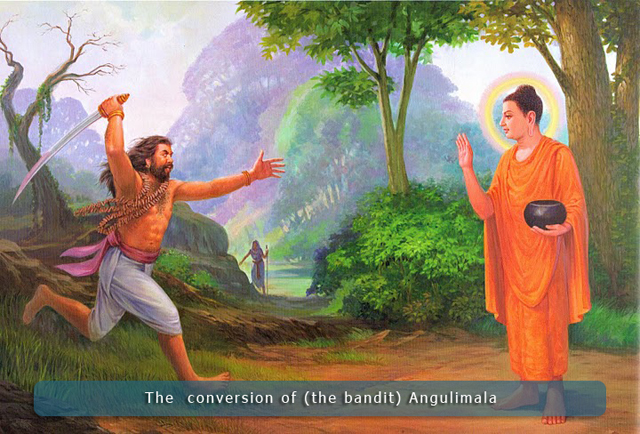

The book describes itself as a “translation” of a traditional Buddhist folktale—the story of Angulimala, a brutal killer who is transformed after encountering the Gautama Buddha in the forest and who then becomes a venerable monk, enlightened and non-violent, an example of the possibility that one can transcend the viciousness of one’s past self, however dark it was.

In Chi Vu’s Anguli Ma tale, the monk in question is an enigmatic figure threaded throughout the narrative, one who appears to hang out in a local park. He interacts with no other central characters in the story save for the “brown man” he encounters there and whom we eventually connect to the personage of Anguli Ma, the errant boarder.

The writing in Anguli Ma: A Gothic Tale is terse, graphic, at times beautifully compressed and charged with insight. The story never explains its themes, just presents its often macabre details in sharp, precise relief. The characters are likewise sharply drawn, never explained. We get to know them through their prejudices and suspicions and delusions, as well as through their plainly described yet still cryptic actions. The fragmented structure of the tale reveals itself by the end to be circular, the “monk” appearing as a potential evolution, or one and the same, as the “brown man”—the moniker used to refer to Anguli Ma’s cruder, more barbaric self.

The fact of, and the paradox inherent in, a people or population born of violence is what struck me most about this short tale. I think the question of whether (not to mention how) we can transmute and transform beyond that past, violent self is left still unanswered, to a large degree. Although Anguli Ma attains his enlightenment to arrive at a state in which his hands only “faintly remember blood” and his mind no longer houses anger, other characters in the story—namely the landlady Dao—appear to be still hanging in the balance by the book’s end.

I think there is much more that can be investigated in, said about, and read into tales such as these (Chi Vu’s is perhaps not the only one) that show us where the impetus for vengeance, the clinging to bitterness and insecurity, the grasping (often through material means) for security are harbored in the Vietnamese psyche. Often these traits are located in the matronly characters, in the matriarchs of our stories—those who have suffered loss, violence, the desperations of remaining. In Chi Vu’s short novel, it is Dao, the elderly landlady, who shows us these tendencies: she hoards useless items in her cluttered house (like the immigrant ever aware of the potential for imminent and sudden loss) and stashes bundles of cash in random hiding spots amid her hoardings; she is the one in the end who is left still eager and thirsting for vengeance against Anguli Ma for what he has taken from her, heedless of whatever transformation may’ve ensued in him through the influence of the monk.

There is a lot to ponder packed into this short, small offering of a book. A tale that exists on the fringes, that both obscures and elucidates the subject of what has been carried out of Vietnam post-1975, psychically and otherwise.

Dao Strom, a regular contributor to diaCRITICS, is the Oregon-based author of the the novel Grass Roof, Tin Roof and the short story collection The Gentle Order of Girls and Boys. She is also a musician with two albums, Everything that Blooms Wrecks Me and Send Me Home. More info here.

________________________________________________________________

Do you enjoy reading diaCRITICS? Then please consider subscribing!

Please take the time to rate this post (above) and share it (below). Ratings for top posts are listed on the sidebar. Sharing (on email, Facebook, etc.) helps spread the word about diaCRITICS. Join the conversation and leave a comment! How can we who have emerged from war and other kinds of violence leave those pasts behind? Is it harder for women than for men to do this?

________________________________________________________________

Dao, thank you for this review. The story is fascinating. You are right that this is more than a “Viet” story and has universal resonance. I’m going to try get it and will leave an update here about my thoughts. Do you know if it’s available on Kindle?

Thanks for reading, Audrey. I hope more will look for this book, obscure little stories like these seem to get lost too easily. I’m not finding Anguli Ma on Kindle, in fact, but there is a link on the publisher’s site about their e-books and it looks like the best thing to do is email the publisher and let them know you’re looking for it as an e-book… It looks like a very small publishing house in Australia, so it would probably help to let them know readers are looking for it…. http://www.giramondopublishing.com/giramondo-ebooks-available-now