diaCRITIC Jade Hidle takes us on the road from Little Saigon and Southern California all across to DC and the Vietnamese American Eden Center. On a trip visiting famous monuments to the suburbs, Jade Hidle contemplates Vietnamese Americans elsewhere.

Have you subscribed to diaCRITICS yet? Subscribe and win prizes! Read more details.

For all my life, I’ve lived just a short drive from Little Saigon in Westminster, California, with access to the largest population of Vietnamese outside of Việt Nam. The area always felt self-contained, complete. I mean this in that my mom and I, without ever having to speak English, were able to conduct our day-to-day business: send money back to Việt Nam, grocery shop, buy jewelry, pray, buy medicine, and, of course, eat.

Even when I was in Việt Nam and anticipating the best Vietnamese food I would ever taste, I found myself comparing—and, subsequently, craving—Vietnamese food back home in California. Of course, my taste preference raises the issue of the quality of ingredients, which is a topical material reality to address in light of the infuriating recent news reports about the smuggling and selling of spoiled meats in Việt Nam . I wondered if the food was similar in Vietnamese communities across the U.S. Was Californian Viet food a culture within a culture? What were the variations of flavor and how would they hit my tastebuds differently?

Sure, when I was ten, I visited a Vietnamese American community in New Orleans for a family wedding, and gained exposure to communities of shrimpers and fishermen. All I remember is that my lips swelled from the spiciness of crawfish. I’d read about scatterings of Vietnamese across the east coast and Midwest via sponsorship and adoption. Once, while watching a Washington, D.C.-based episode of Anthony Bourdain’s No Reservations, the prolific host was reprimanded for filming in one of the restaurants. Certainly, they have their reasons to make such a request, but this only intrigued me further.

This July I had the opportunity to visit our nation’s capital. (Dear reader, I care about you. So listen up: Never visit D.C. in the summer. The sun boiled my internal organs, and, liquefied, they seeped out of my body in the form of tears.) The magnitude of the city’s history and the number of monuments, plaqued buildings, and Smithsonian’s army of museums is all terribly interesting and stimulating and, sometimes, infuriating in its manipulative elisions and artifices.

All of the information and sheer visual stimulation swirls whirlwind—at least when you’re trying to knock it out in two days.

The White House? Yeah, camera click on the building, then on the nuclear weapons protestors camped across the street.

Ford’s Theatre? Nod a quick pay of respect. (And note how differently Lincoln is historicized here–a hero–than in South Carolina–a duplicitous racist.) I often couldn’t decide whether taking pictures or refraining from taking pictures was the more respectful thing to do.

Washington Monument? Though a huge Egyptian-plagiarized penis and its reflection, it is a goosebump-raising site of gathering and protest.

Lincoln Memorial? Remember the great Dr. King at the top of that staircase and then smell people’s different scents of sweat at the top of the staircase. Won’t, and can’t, forget it.

In the National Gallery, all of those beautiful paintings by mostly non-American artists? Yes yes yes, soak in the strokes of color and the air conditioning.

Then, amidst all of this noise, color, and neck-craning height, the record scratch.

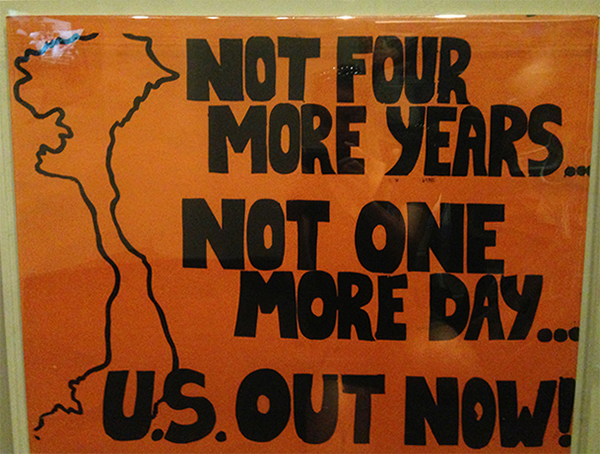

In the American History Museum, an exhibit on military history entitled “Price of Freedom” narrates, if not glorifies, the major wars (and by “major” I mean publicly recognized) in which the U.S. has participated. The exhibit features a one-room display on the U.S.-Việt Nam War.

The exhibit primarily focuses on the presidents involved in the war, and the Vietnamese are largely underrepresented here, their visibility limited to the iconic Nick Ut and Eddie Adams photos for the Associated Press. Also, the beginning of the exhibit presents an Army of the Republic of Viet Nam (ARVN), or South Vietnamese Army (SVA), uniform, the placards for which point out the American-influenced style of one of the badges, and a Việt Cong uniform at the end of the exhibit. The display case of the latter uniform also includes some small homemade weapons and torture devices. Within the space of this exhibit, these uniforms are marginal, flanking the Huey helicopter in the center of the room.

When I started writing this post, I wanted to show you what I described above. I think it is telling that, among the hundreds of pictures I took on the trip, I don’t have any photos of this exhibit. I was struck. All I have is this, from another exhibit on protest:

I started tearing up a little bit in the war room. Why? I still can’t pinpoint, or at least articulate, in any way that is both long and short enough. Maybe it was that the pictures and the uniforms polarized Vietnamese into victims and foreign combatants, respectively. Maybe it was the way children in the exhibit excitedly flocked to the helicopter, that emblem of the aerial nature of the U.S.-Việt Nam War, and feeling the overwhelming responsibility museums bear on younger generations’ understanding of history and militarism’s shaping of the optics with which they approach the future. Maybe it was the way a man shook his head as he peered into case containing the Việt Cong torture devices, as if they were the only ones committing inhumane acts during the war. And maybe it was the passing thought that someone might recognize the tattoo on my arm as the Vietnamese language and an alarm would sound, signaling the crowd to judge me for being the outsider I already felt like in viewing this exhibit’s portrayal of the war in a different way. Maybe it was all the things I couldn’t see.

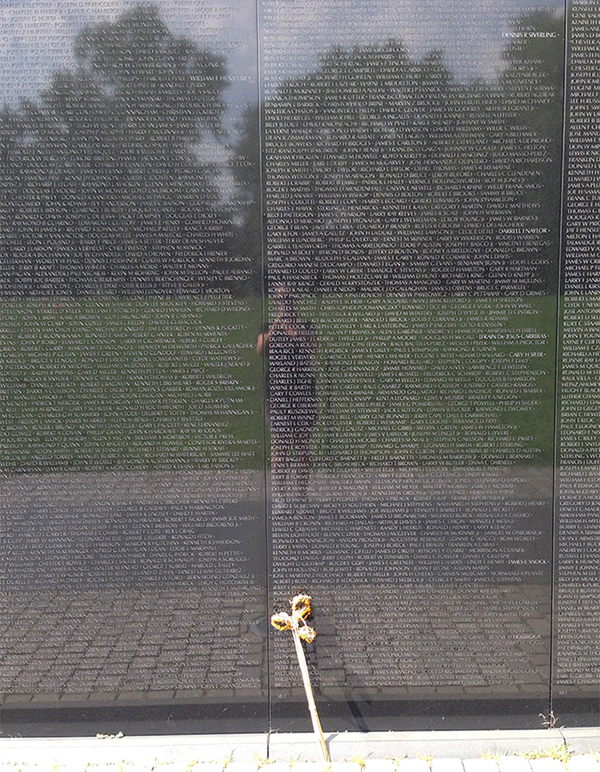

Maybe it was all of these things that at once numbed and overwhelmed me when, after the museum, I walked over to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. The number of names weakens the knees. So many names, so many young men and women lost. So many not named, and so many who became Americans because of what they had lost. My dad found the name of his cousin, which was emotional. This cause of this relative’s K.I.A. death merely reads, “Hostile,” followed by the caliber of bullet that killed him. Hostile. That word stood clear in waves of waves of heat. Catching my reflection in that iconic wall, I thought of my mother and how there is no place for her to go to find the names of those she lost.

I had read so much about the memorial before visiting it in person—its design, construction, and ensuing controversy over Maya Lin’s conception of the memorial as an irreparable wound, a descent; critics accused that it was too dark, even too vaginal. (Hold up! For anyone out there who has used any word for the vagina to insult anyone or anything for being weak, take a minute to think about strong a vagina is. Really. Your human head, along with its brain that would go on to misuse vaginal metaphors, came out of a vagina.)

This latter critique rings appropriate because, in my short stay in D.C.’s National Mall, I was left with the impression that “official” American memory desperately holds fast to a staff of righteousness (oh yes, the phallic metaphor is intended here, in the land of pillars, obelisks, and columns). My position to said “staff” is elastic, questioning, straying and exploratory. When it comes to matters of such complex histories and navigating my way through it, I feel like the line in The Pixies’ song “Velouria” that calls for us to trampoline to “somewhere near and far in time.” And that’s what I wanted to do in D.C. In all of city’s space filled by towering buildings that declare, “America, Fuck Yeah!” where is that place where the women cooks were badass enough to tell the rich and famous chef Anthony Bourdain to shut his. Located in Falls Church, Virginia, approximately 10 miles across the Potomac River from central D.C., Eden Center is a strip mall of delis, restaurants, and music and jewelry stores. Eden indeed.

To enter the shopping center, I drove through a Chinese-influenced archway, like those that mark the borders of Chinatowns in almost every city I’ve visited. Crossing under this emblematic architectural threshold marks the passage into distinct cultural space. To edify this space, the street names are in Vietnamese.

Posters in the shop windows advertised the area’s upcoming second annual heritage event—talent shows, entertainment, and a beer garden! As you can see in the poster, the event is put on by the National Organization for Vietnamese American Leadership (NOVAL). NOVAL, I learned, is a D.C.-based non-profit organization serving the socio-economic and cultural needs of Vietnamese Americans in the great Washington area. And this is their second annual event. That means, although new, the culture and community is growing, NOVAL is serving its commendable mission.

My travel schedule only permitted stopping by Eden Center for about an hour on a Friday morning, so there were still some stores that were closed, and my stomach wasn’t awake enough to going on an eating rampage that an evening would allow. And phở does not sit well when it’s already 90 degrees and 80 percent humidity by 9 am. So I played it safe and simple.

Nestled in a corner behind a fountain (I, sweating profusely, was ready to drink from that sucker), Song Que Deli beckoned to me. Though visiting for the first time, I felt as though I could deftly navigate it in the dark. It is laid out like most of the Vietnamese delis back home: against the wall, pre-packaged favorites like shrimp chips, those Yan Yan chocolate dipping sticks my sister likes, and canned soymilk or sửa đậu nành. (Dear reader, why does it always taste so much better canned? Am I hooked on preservatives?) In the display islands in the middle of the store, fresh jackfruit, guavas, lychees, along with multicolored bánh bo and other rice and jellied to-go desserts on Styrofoam trays wrapped in plastic. At the counter, fresh smoothies, boba, bean and black-eyed pea chè puddings, gelatins, ice cream, and the fluorescent glow of the sandwich menu. Most customers were taking their orders to go in plastic bags with happy faces on them, but there is also a quiet dining area in the back.

As per my friend Sal’s sage advice, when I try new places to eat, whether Vietnamese or Mexican or Italian, I like to start with a basic dish, to test out what they’re working with. After all, if you go to a new Mexican place and their bean burrito tastes like pipe sludge wrapped in a wet sock of a tortilla, you know that the rest of their menu will be a struggle going in. And out.

Under the wing of this alimentary guideline, I started with a staple at Song Que: bánh mì chay, or vegetarian sandwich. If you’re like me, you are frustrated, even a little grossed out, by the thin strips of fried tofu in Lee’s Sandwiches rendition of bánh mì chay. They kind of look like…skin. Burnt skin. My mouth dries out from all the bread, which sometimes scratches the roof of my mouth in the way that Cap’n Crunch cereal does when there isn’t enough milk in the bowl. Not Song Que’s bánh mì chay. This sandwich was packed with meaty slices of tofu. I know, I know. The irony of my desire for American-oversized, meat-like slices of tofu is evident. But just because I’m ordering vegetarian doesn’t mean I don’t need something to sink my teeth into.

The tofu is flavorful as well, marinated in what reminds me of the tastes of tofu in temples at Têt time. (I’ll take a bow here for that Seussian string of alliteration.) It tastes like a mixture of soy sauce and spices that aren’t easily identifiable to my unsophisticated palette, but whatever it may be is both salty and savory. The tofu was in bed with the usual pickled carrots and daikon, peppers, and sprigs of parsley, but the female deli chefs (why don’t we have a word for those working hard behind the counters of delis everywhere?) at Song Que also slather hot mustard in the crease of bread, which added a tang and spice to the sandwich that mayonnaise simply cannot do. Mayo, you belong with fried bologna and white bread.

To accompany this satisfying sandwich, I chugged a can of sửa đậu nành, along with a chè ba màu (literally, chè of three colors), scooped fresh to order, and a taste of a sinh tó xoai (mango smoothie), which is made from fresh mangoes, unlike the gelatinous, fructose-y smoothie mixes at the many boba places mushrooming Starbucks-style in some big cities.

Comforting, too, was that the people were very nice. The young hipster girl, whose finger hovered over the cash register because she was being trained on her first day of work, was sweet in her smile and thanking me. She and her boss did not give me any funny looks or questioned my ethnicity when I spoke in Vietnamese. Likewise, the older woman in the music store where I stopped to pick up some DVDs talked with me about regrettably washed up singers, as well as the challenges and rewards of teaching children Vietnamese. Such ease of conversation is not always the case back home or in Vietnamese American joints I visit in other places, and usually proves to be the test of where I choose to shop again. I was happy and relieved to not be made to feel like an outsider in this space.

At the same time, I was clearly not at home. At the end of my conversation with the woman in the music store, she said, “You’ve traveled far, haven’t you?” I am, through and through, a California girl, and I can’t possibly begin to understand the cultural, socio-political, and geographical factors in D.C. that inform the Vietnamese American community there, as well as the multitude of other cultural groups in the sprawling city and its suburbs.

Reader, this is clearly no culinary review (I do not eat in, or speak the language of, fusions or molecular gastronomy or some modern art experiment of 0.4 ounces of food whipped into a ganache and smeared across the plate that leaves my stomach growling for something more), nor an attempt at the impossible comparison between different Vietnamese American communities, all of which are unique cultural spaces. This is just to say that, with the short taste of Vietnamese D.C. that I got through a seemingly simple sandwich, I found comfort in the fact that, even though Vietnamese people have been edged out of the “official” space in the National Mall, in Eden, flags fly side by side.

Jade Hidle is a Vietnamese-Irish-Norwegian writer and educator. She holds an MFA in creative writing from CSU Long Beach and is working on a PhD in literature at UC San Diego. Her work has appeared in Spot Lit, Word River, and Beside the City of Angels.

Do you enjoy reading diaCRITICS? Then please consider subscribing!

Please take the time to rate this post (above) and share it (below). Ratings for top posts are listed on the sidebar. Sharing (on email, Facebook, etc.) helps spread the word about diaCRITICS. And join the conversation and leave a comment! Have you been to DC? What are your thoughts on the official presence of the Vietnam War? And what about the DC Vietnamese food and community? Tell us! We want to know!

Great article! I’ve had the pleasure of visiting Westminster’s Little Saigon, but I’ve only been to DC once, so I’ve only seen a fragment of what the city has to offer (and I must confess, I spent most of my time there lurking around the Air and Space Museum like the science dork that I secretly am). This is such a vivid, detailed account of a part of the city that I only scratched the surface of during my visit. Now I not only want to travel again, but I could really go for some Yan Yan and some of that delightful “meaty tofu.”