‘Flicisme’ is a term coined in the 1970s by them, those Vietnamese then reckoned the promising figures of a generation of young writers of North Vietnam. Carrying with them a French- and/or American-influenced background, they joined force to form in Vietnam a generation of intellectuals whose voices have been squashed, screened or serenaded depending on the social and political tides of the country. ‘Flicisme’ came from flic, French for cop. These writers’ experience with ‘flicisme’ reflected the pervasive presence of undercover cops at the time in Hà Nội, which in and of itself was evidence of a strained relation in an ideological power struggle between the state and the people. This reality was captured in Trư Cuồng written by Nguyễn Xuân Khánh, one of those ‘young writers,’ and reviewed here by another, Hoàng Hưng. The original article is in Vietnamese and published on vanviet.info, an independent website of Vietnamese writers in the country promoting unrestrained artistic expression.

Thirty years have passed since the last time I picked up Trư Cuồng (Porcine Mania), yet the feeling it calls forth stays the same. The first time I read the book was during my tumultuous trip to Hanoi in the Fall of 1982. In a small house near the black and putrid Kim Ngưu river, the author entrusted to me his written manuscript which was only circulating among a handful of his chums. The novel kept me sleepless.

Just its realist depiction of the wretched life of a family of a writer and journalist alone is enough for readers to succumb in awe to the charged realism of daily life so astutely captured by the seasoned author. The family life revolves feverishly around the pigsty, the pigs’ well-being and daily weight gain being a matter of life and death for them. Then readers get to witness the pigs gobbling up Chekhov’s and Dostoevsky’s bare bones and brainchilds, the “pig-malion enforcement” rendering the husband impotent.

This historical narrative depicts a bygone tragicomic era in which the entire Hanoi’s population plunged into pig raising as if it were the only way out of poverty. And not just Hanoi alone. At that time, in Saigon, the number of apartment dwellers who raised pigs was so high that in many cases all the sewer pipes were clogged.

Punctuating this overarching narrative are the heart-rending stories of defected soldiers, called B-quay, whose backs were forced against the wall; the bitterness of disillusioned intellects who sacrificed their youth for a lofty ideal only to realize that such an ideal was incompatible with everyday life; and the phantom of state persecution, with interrogations, surveillance, setups, betrayal, etc. employed by the state security apparatus to terrorize writers subscribing to “subversive” ideologies.

(I remember that long ago I once joked that my seniors from Hanoi such as Dương Tường, Xuân Khánh, and Châu Diên were haunted by ‘flicisme’—they saw ‘flic’ everywhere and thought everyone was a ‘flic.’ In my 1973 poem Người đi tìm mặt (The man who is looking for his face) there is a string of images “Mặt ga đêm/miệng mở ngủ/Giật thức/ mắt kinh hoàng” (The face of the dark train platform/sleeping with mouth-wide open/Starting up/eyes in fright) which points to that very spooky omnipresence. Not until I was detained in the Về Kinh Bắc case did it dawn on me that my seniors were not simply paranoid.)

Just the gripping social realism of Trư Cuồng alone transcends the comme il faut reality portrayed in orthodox literature of the past decades. But it does not stop at that! What never emerges from that sea of poor prose is an unfeigned concern over pressing social, ideological, and philosophical issues. The reality of “pigs and men” in Trư Cuồng, however, professes just that genuineness in streams of consciousness, though in many instances its author momentarily relapses into commentaries, soliloquies and dialogues (which appeared even in interrogations).

Everyone knows that there was a time when “thinking” was deemed dangerous in our nation. Thinking, or “counter/anti-thinking,” about political ideology could be hailed as the most courageous act committed by generations of intelligentsia working and living in Northern Vietnam. Although I refer to “act” in a philosophical sense, it nevertheless carries a legal denotation for the authority when they persecute these intellects. Back then, it only took a small gathering of a few who dug up the question Que faire? (the title of a work written by 19th century Russian revolutionary democrat Nikolay Chernyshevsky) to constitute an “act,” or even an “organized activity,” which was enough to earn one an ever-expanding-sentence [called “rubber-band-sentence” in Vietnamese] that might last a life-time. (Perhaps the bloggers or political dissenters of today can see that the repressive motif remains though its degree of severity may vary.)

There is still more! What most tormented the author of Trư Cuồng—what his train of thought ultimately arrived at after being propelled by the “pig” reality—was the “pollution” of the pigsty which was poisoning human society. In fact, man has always had a ‘pig mindset’ inside throughout the course of history. What is its nature? For the author, “the pig mindset” is:

“Let’s just eat and eat only, even if there is only water fern to eat. Let’s just eat until our belly bloats to the size of a barrel, and then the feeling of satiety, of satisfaction, of happiness will come. The cardinal rule is not to think, for to think is to breed evils”.

The then modern political regime had fostered that “pig mindset” so well that it had turned into a cult of porcinism whose butchers followers were crowned kings with their spine-shivering “cut-throat” life philosophy. It got even more alarming when these butchers, or their offspring, who no longer felt obliged to wear a blood-soaked shirt and wield a sickle in their hands, still managed to “cut-throat” society with perfect impunity while donning the latest fashion, which was sometimes tagged with the spanking “made in USA” label, and thriving in tangled webs of connections and constitutional privileges.

Worse, those once passionate youths themselves, clicking their tongue, now gave an excuse for literally giving up Chekhov, Dos [Dostoevsky], Sartre, etc. to the pigs by pointing to the primordial call of the belly (isn’t it not very far from those slogans such as “vivre d’abord”—let’s live first, “let’s get by first”, or “let’s settle down first”?) only to become the “sons-in-law” and disciples of the butchers before they even realized it!

Nguyễn Xuân Khánh was a real pessimist back then. His porcine paranoid (or Porcinomanie, a term coined by the author to denote the bad habit of living like a pig) induced a nightmare resembling that of George Orwell’s Animal Farm, a utopia in which “human’s greatest minds” scheme to pull a fast one on mankind and in which Citizen No.1 appears in his true form as a pig named Cow. Then, he woke up to the sight of his philosophy-aficionado-son’s resorting to the butcher’s sickle to appease the entire family’s stomach!

What could he do but change into a veteran, then climbed to the top of the tree to cry out his hopeless warning “Por..ci..no ma..nie…” before falling off dead in the middle of the bewildered crowd.

That thirty year-old warning remains intact. The author’s foreboding is slowly becoming a cold, hard reality in this country: the cult of Porcinism has grown into a national crisis in the form of corruption and shady dealings, an impudent and shameless lifestyle, and the regression of culture and education to a red alert level. Meanwhile, the author’s heartfelt warning is still locked behind the bars of censorship. That is a crime!

Not until 2005 could readers get their hands on an online version of Trư Cuồng published on the online library of Talawas thanks to Châu Diên.

To conclude this article, I would like to reveal an anecdote related to Trư Cuồng which, had it came to light thirty years ago, would have been treated as an earth-shattering scandal.

On August, 1982, before I bid farewell to my seniors and returned to Saigon, Mr. Khánh said to me in a dead serious tone: “Can you think of a way to print out my Trư Cuồng? It doesn’t matter where. I am ready to accept any consequences.” I promised him I would, but deep down I truly had no idea how to fulfill his ardent wish. Back then “Samizdat” (a form of self-publication appeared near the end of the Soviet era) had not been practiced in Vietnam. Sending the manuscript oversea would be too dangerous, and I myself did not know how to carry it out. But I promised him anyway.

At the last minute, I suddenly feared that the manuscript would be discovered along the way due to custom inspection targeting goods travelling back and forth between the North and the South. I mainly earned my bread in trading them because I could not possibly survive on my meager salary (I would bring cameras from Saigon, and films and photo paper, rolling tobaccos, tobacco rolling papers, liquid lard, etc. from Hanoi). So, I entrusted the manuscript to one of my colleagues who was a good person despite his party membership, and who was also the brother of Director Lâm Quang Thiệp—Mr. Lâm Vinh. He was more than ready.

The day he came to my house to pick up an introduction letter with Mr. Khánh, he found out that I was just arrested. Indeed I was evading the frying pan only to jump into the fire! I was arrested not because of Trư Cuồng (which at least makes sense because it was truly “reactionary”), but because of (how ridiculous) Về Kinh Bắc (To the Northern Capital) [a collection of poems by Hoàng Cầm].

In 2006, I and Mr. Khánh both received awards from the Hanoi Association of Writers for my poetry collection Hành Trình (My Journey) and his novel Mẫu Thượng Ngàn (Princess of the Forest), respectively. Standing next to each other on the stage, he almost spilled the beans about the aforesaid story which took place thirty years ago, but fortunately checked himself.

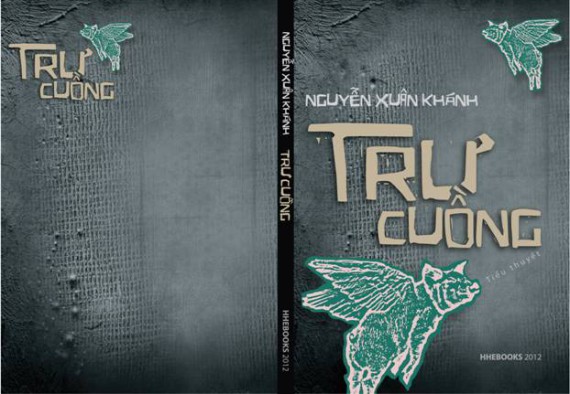

But now I have related it in its entirety, for I have finally fulfilled the task entrusted to me thirty years ago. And here it is, the fourth book in my HHEBOOKS library [a e-library created by Hoàng Hưng to circulate any book of his own choice among his own email circle]. It was created from the PDF version converted from the file of Mr. Châu Diên, with some minor typos corrected, who requested that a cover be made so that the book is ready for print publication when possible.

–

Translator: T.K.

Author, journalist, and translator Nguyễn Xuân Khánh (b. 1933) is a notable figure from the generation of “young Northern writers” in the 1950s. In the mid-1960s his works were barred from publication due to his “revisionist attitude.” It was not until after the Đổi Mới (Renovation) era did he stage a comeback, which produced instant success, with many historical novels. Among them are Miền Hoang Tưởng (La-la Land) and Trư cuồng (Porcine Mania), which focus on contemporary society as their main theme; the first was denounced by the government upon publication and banned from republication; the latter received a national proscription still in effect today, and can only be accessed on talawas.org and kesach.org.

Hoàng Hưng (b. 1942) is a poet, translator, and journalist. One of the celebrated young poets of the so-called “Anti-American Generation” in North Vietnam in the 1960’s, he turned into one of the “underground-avantguardist” poets in the 1970’s whose poems had to wait until the “Đổi Mới” era to be published. His writings and poems were refused by the press and publishing houses in Vietnam after the emergence of the Ban Vận động Văn đoàn Độc lập Vietnam (the Campaigning Committee for the Creation of the Independent League of Vietnamese Writers) and its Online Forum vanviet.info of which he is a co-founder.

Do you enjoy reading diaCRITICS? Then please consider subscribing!

Please take the time to rate this post (above) and share it (below). Ratings for top posts are listed on the sidebar. Sharing (on email, Facebook, etc.) helps spread the word about diaCRITICS. And join the conversation and leave a comment!