“don’t you dare speak of this

grief tied around our mouths

the most effective gags are the ones

we tie ourselves

make silence a ritual

name it Brave”

– from “I. Altars”

Daring to speak of this and so much more, Phuong T. Vuong opens The House I Inherit. Part I, “Altars,” breaks the silence, asks questions, engages the past. In “What my father gives me,” Vuong writes:

my father who gives me

salted lemons

makes offerings

when my silence seems

too prickly for much else

my father so good

at surviving

even his preserved lemons

stay afloat in salt water

Through both what is said/spoken and unsaid/silent, Vuong gradually reveals poem after poem—67 in all, in three cohesive parts that form this whole, integral book. These are unsettlements, invocations, reflections, celebrations, responses, becomings, rages, shames, and healings. They evoke. They challenge. They place us in moments of frustration. Love. Tension. Resolution. Discovery. In them, Vuong explores a wide range of emotion and experience, grounding her work in immigrant/refugee/diasporic existence and moving beyond it into new worlds, new visions. In “Forge” she writes:

i dive off cliffs of my own paintings

swim in the deafening silence of my own home

oceans cry a face of salted gems

gifts for bà nội

and children not yet made

i look back

this other watery passage

briny cemetery

no one remembers

our Pacific diaspora

lost at sea as boat people

but i believe in the past

i tell the stories

this ridiculous act

to parents who just wanted food on the table

i mold new worlds

forget my thin fingers small hands my woman’s heart

forge a new steel a saltwater organ

new thing for loving and knowing because i a woman can

And I am moved. I turn Vuong’s “new worlds” over and over in my hands. My heart. My mind. I am drawn inward and across the Pacific Ocean. With her words, through her words, I brush my own brown body against others’. She writes, “we meander through poems”, and I do. I think of love and loving. Of joy(s) and pain(s). Of race. Of irony. I think of Sophia E. Terazawa and her essay “Rites of an Old War,” where she writes, “What I am trying to say is that it hurts. Loving a white man hurts.” Terazawa asks questions of our love and our loving, of what it means to love and risk in silence and in speaking. Vuong’s poems work with and through and around these questions, compelling us to consider our bodies—our knees, skin, fingers, and limbs—and to consider the ramifications of our love(s).

The texture of Vuong’s words takes me right to the tangible, right to the corporeal self in poems such as “Brown love” and “Flesh” and “I want you to.” In “Loving in the borderlands,” she writes:

you and i

borders wide as the Pacific

the expanse of beach to a boat

rocky desert to a 20-foot wall

the bombing of countries and tribes

or distant like our hunched backs

and

so for now

you and i sit

in this little peace

neither here nor there

not yet arriving nor departing

loving as the children of migrants

Vuong touches the visceral through successive and powerful images. This, from “In the morning light”: “like dawn on my thigh/a morning meditation on yellow”. I read this and feel the sun’s rays on my own leg. I reflect. I meditate. And this, from “Ocean tide”: “alone but you occupy one/remember our sleep/my leg crossed over your brown torso.” I am there, feeling the rasp or smoothness or slide of skin. The complexion of brown torsos, crossed over, being crossed. Vuong’s words are vital and textured. They are full of being.

In “Write into it,” Vuong utilizes repetition and strong imagery to bring the reader to and across the threshold—an existential awakening, a birthing—to the immediate Now.

She writes:

i am writing myself

i am writing myself

i am writing myself into

myself into

into a line

they didn’t say existed

into a legacy of open-mouthed women

whose screams they beat

gagged into shame

and

i am writing myself

i am writing myself

into you

teeth bared

fists readied

fingers still soft

for peeling peas

and holding babes

if i choose

i am writing myself into

i am writing myself

myself

into

being

In the epigraph, Vuong quotes Stuart Hall. “Cultural identity,” Hall writes, “is a matter of ‘becoming’ as well as ‘being.’ It belongs to the future as much as to the past.” It’s a fitting beginning to Vuong’s book.

Part I, “Altars,” brings us to the past. To family. To history and memories. To the shared and isolated. To specific scars and to generalized, vague, elusive traumas—the legacies of our diasporic and refugee pasts. Our war-torn, war-stained, war-silencing heritage. Our ancestry. And more. Part II, “Self-Portraits,” goes further. Deeper. Inward. In “On remembering—note to self” Vuong writes,

“you could live many lives excavating that which is hidden, lost, or silenced. but sometimes the past has been there all along; the places your bones ache, those names you know, those you do not, why your father sleeps fitfully, how you know to sauté shallots in oil, carry guitar like life preservers, and green thumb like machete and spoon. you know why we need the land and how we always make due. trust in that. the love of heat and humidity.”

There is this remembering. And more. Part III, “Doors,” takes us to love. To fruit. To possibility. Fecundity. And more.

As a whole, The House I Inherit propels us inward and outward. To the past. To the future. To the oceans. To our collective history. And to our families. The individuals. The histories. The legacies. What we inherit. At the same time, it ties us to our present(s), to the places we inhabit. To our loves. Our bodies. Our futures. Our fears. Our stories. What we pass on.

Vuong intertwines specific, anchoring imagery along with ephemeral, transitory existence(s) to remind us of ourselves and our surroundings. Our past across the Pacific Ocean. Maybe in Huế. Our present. Maybe in Fruitvale, Oakland. And our future(s) are here too, in the stories and poems that we tell and through which we “meander,” the worlds that Vuong has “forged.”

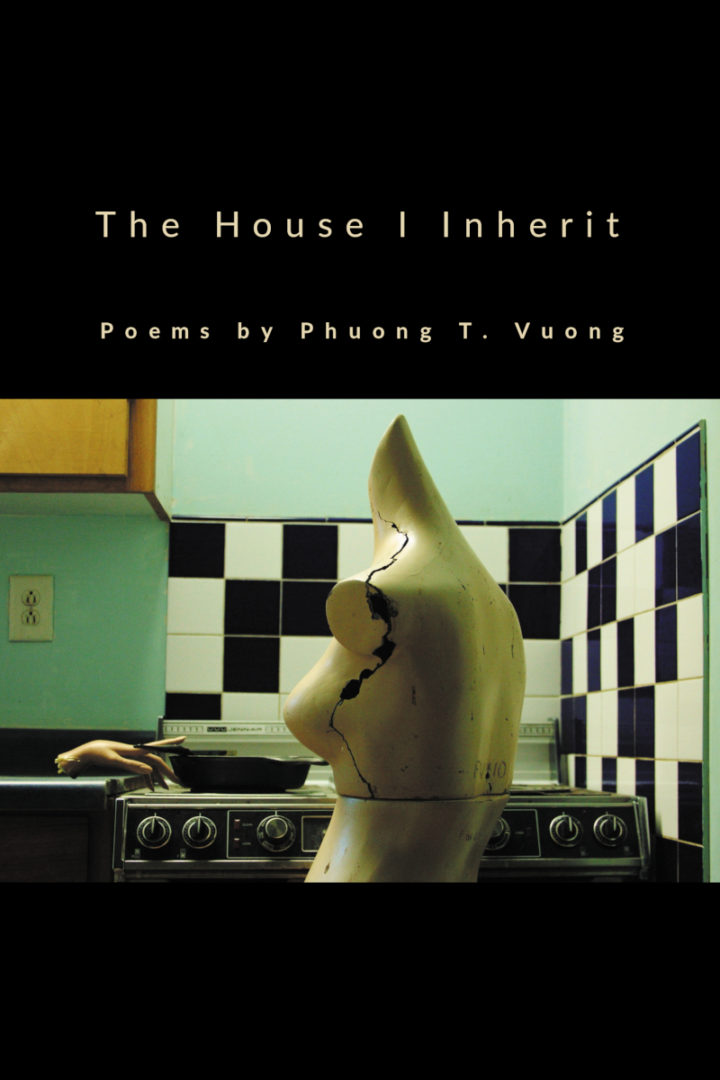

The House I Inherit

by Phuong T. Vuong

Finishing Line Press. $19.99.

CONTRIBUTOR’S BIO

Paul Bonnell was born in Buôn Ma Thuột, Vietnam. He has lived in the Philippines, Malaysia, and the United States. He teaches, coaches, writes, plays music, and climbs in northern Idaho, where he lives with his family. He is interested in poetry, essays, fiction, hybrid art, the Vietnamese Diaspora, the Chăm, the Bru, mountain culture, biopolitics, and transracial/transnational adoption.