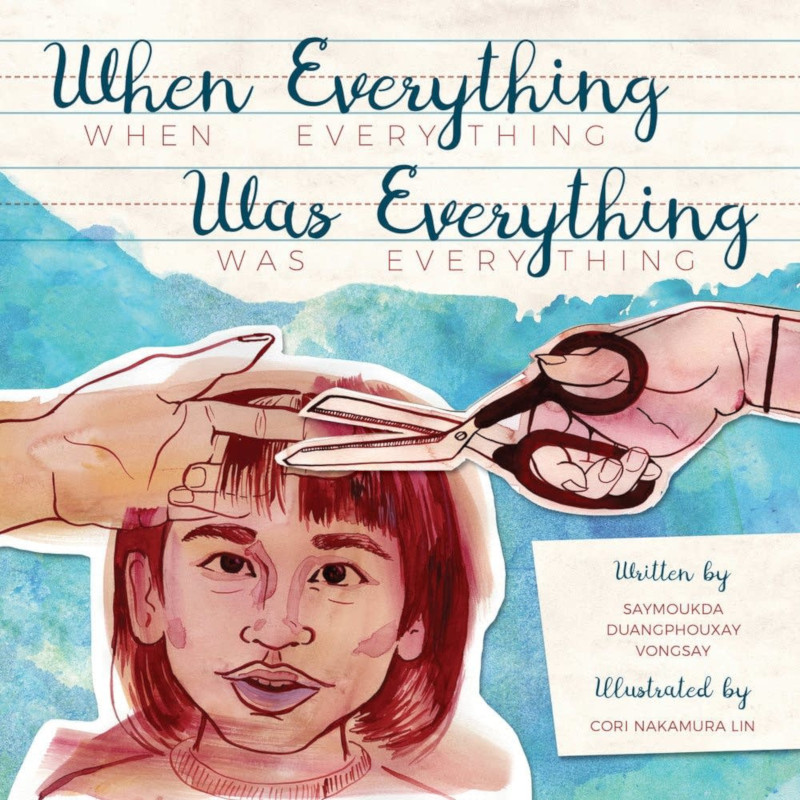

Some books are written for the sheer joy of a story a child would pick up and read, with or without an adult. Saymoukda Vongsay’s children’s book, When Everything Was Everything, isn’t one of those.

It’s so much more than that.

When Everything Was Everything is a spinner of memories. It’s an emotional unraveling I get to experience while holding my two children in my lap and explaining, line by line and word by word, the humanity of linking past with present, children with parents, heritage with intimate culture. That intimacy is felt in the first wash of color across the page: a nostalgic green-yellow as the backdrop to descriptions about tart fruit, chili sauce, and Now And Later candies. Each page that follows is painted in one or two colors; each page that follows is illustrated in beautiful and muted tones. It creates a reading experience that is slow, careful, and quiet. The hushed tones of each scene make my children whisper as we move through the book.

The text itself moves like ribbons of mixtapes at the bottom of the pages: the words cleverly follow each ribbon path, mimicking the playing of a tape as it yields the words to a song. Words are color synced with each illustration, either by subject or by direct description: No. 2 pencils and Sun-Maid raisins bring forth smooth, bright hues of gold; a blue ox “as big as a house that lived in a magical place” paints everything in blue. Page after page, these scenes, synchronized by color, beautifully illustrate and reproduce the emotions that anchor memory.

And, like a mixtape of memories, the book offers a sequence of vignettes meant to garner an overall emotional response, a mixtape motif that captures moments and a message in time. I’m reminded of a time when mixtapes were exchanged between friends and lovers: I made this mix for you. The list captures how I feel. People tried to say things with their list of songs. A mixtape could be a mishmash, but often it wasn’t. Vongsay’s mixtape also says something: it is a precisely detailed trek through a girl’s past, splicing Laotian culture with the American 80s, and refugee identity with the strange and mundane and comfortable. We feel the familiar through the unfamiliar: “haggling with Hmong grandmothers at the Farmers Market” is another comforting microcosm of the familiar in a world that is still strange to her, and that she is a stranger in. One gets the sense of holding onto these miniature worlds as a process of acclimation, as a point of rebellion, and as a central part of her refugee identity.

As a refugee, it’s the affliction of being displaced.

The displacement felt in these moments is like a gut punch, and I can feel my children feeling it, through my feeling it. They watch me as I read to them. I, too, am a refugee, I tell them. What a thing it is to be removed from a land, to flee from it, to begin again. As we read together, I remember food stamps. I remember free cheese and rice. I remember bowl haircuts that made me feel like I didn’t belong. In dim lavender illustrations, the narrator explains that her family had “itchy feet,” and moved from place to place. The secondary illustration– the one that moves across the minds of readers as they read—is of the difficulty of anchoring, of growing roots in a land you don’t yet belong to. The itchy feet is about being lost, about being a ghost. One doesn’t have to be a refugee to understand that, about not belonging. One doesn’t have to be a refugee to understand that.

And one doesn’t have to be an adult to understand that. Children understand the loneliness that comes with moving. They understand the isolation of not sharing a language. They understand the joy and strength of family when the rest of the world doesn’t understand you, verbally and culturally, and they can see it illustrated in the moving van—Pahw’s Isuzu—a microcosmic home in which a family can eat, sing, and buy lottery tickets (hopes and dreams) together. My children asked questions about if the narrator’s life was hard, and how her life might change if her family won the lottery. In this book, every page is a memory, every scene is an avenue open for questions and conversations between parents and children.

When Everything is Everything is a book that is to be surgically opened, investigated, and followed in many directions. It’s a labyrinth of thought, a time machine, and a cultural dreamscape meant to be shared and taught and remembered. Does this sound more like a discussion in a lecture hall at the local university than a child’s bedtime story? Perhaps. But perhaps there isn’t much difference between a college lecture and a conversation with children about books (or anything else). And perhaps Vongsay recognizes that.

At some point, my older son put one of my mixtapes into the tape player and pressed “play.” The garbled voice of Tori Amos attempting to sing “China” created a weird fusion with some ancient version of “Túp Lều Lý Tưởng” until the ribbon ran itself into snarls in the machine. The next line in the book we read was “I wish I could remember the song he used to sing.”

The wish to remember is the soul of the mixtape. At the end of the book, when the voice of the ancestors rise in unison with the sound of familiar Thai singers—a common phenomenon when people sing old songs from their history and heritage—it’s literally the sound of the past merging with the culture our children inherits. It’s a love letter carried from past to present. It’s Everything. And, back, then, when we were Southeast Asian refugee children doing our best to acclimate our strangeness to the strangeness of an unfamiliar world, everything mattered. Every detail of our memories captured the song list of a message in a mixtape we want our children to receive. In other words, everything was everything.

When Everything Was Everything

Saymoukda Duangphouxay Vongsay and Cori Nakamura Lin

Full Circle Publishing

$18.95

ISBN: 9781634891592

Contributor Bio

Elizabeth “Lizzie” Tran is a Kundiman fiction fellow, a Lambda fiction fellow, and the recipient of the Jeanne Cordova scholarship for Lambda fellows in 2017. She holds a B.A. from Rollins College, an M.Ed. from the University of California, San Diego, and an MFA in fiction from San Diego State University. Her book reviews, fiction, poetry, and essays have most recently appeared in Brickroad, Vien Dong, Little Saigon, Tayo Literary Magazine, and the forthcoming Foglifter. She is a high school and middle school English teacher, and a mother of two magical little boys. She lives on the shores of southern California, spending most of her days near the ocean she can’t breathe without.