VI KHI NAO: What is the wind like over there? Are you able to describe it. Also, do you prefer Jennifer or Jen? How interchangeable is your desire to be named? Or called?

JENNIFER NGUYEN: The wind comes in wild bursts every few seconds or so. The internet connection is unstable but I’m not sure if it’s the winds fault or not. I heard the wind before I heard my alarm. My mother was trying to nap but it seems she’s given up now and is apprehensively watching the garden for fear of the wind uprooting all of it.

Thank you, Vi, for asking me about my name. In a professional or public setting, I introduce myself as ‘Jennifer’. Among friends and those I’m close with I tend to use ‘Jen’. My Vietnamese name is ‘Nguyễn Khánh Duyên’. My Father uses ‘Jen’ in texts to me. I don’t recall ever asking him to call me ‘Jen’. At home my family call me ‘Duyên’. My siblings have said before that ‘Jennifer’ sounds like the name of a complete stranger. I’m the same, I can’t imagine referring to my siblings by anything but their Vietnamese names as opposed to using their birth/English names.

VKN: What is your relationship with your father like? Are you close to him? If you were to share a poem you wrote, which one do you think he would feel like “a small broken piece/ from a tea set?” Which poem would make him feel like a seashell? (From chapbook with poem title: “My room smells like salt.”

JN: My father is a pragmatic, hard-working, down-to-earth person. And I was rebellious towards every single thing my parents wanted me to be so there were a lot of tense moments growing up, which created a distance, that still exists to this day. There’s a longing to speak intimately and closely with my parents that I work through in my poetry. The poem that would make my father feel like a seashell is the poem ‘“Ba, Mẹ … I want to become a writer. I want to write for the rest of my life.”’ I’ve never said those words directly to my parents and I’d like to, someday.

VKN: Should I assume that most of your poems are autobiographical? If I were to assume that you wish to pronounce your name, what is the most ideal way for you to pronounce yourself? What word does your Vietnamese name rhyme with?

JN: Most of the poems in this chapbook draw from my own experiences. I want to start pronouncing my Vietnamese name correctly, but at this point it feels too late, almost like the correct pronunciation would make it an entirely different name altogether. To rhyme with ‘Duyên’ I came up with mắt kính, chuyện and miếng, but I am not sure if these count as rhymes or not? This is both frustrating and enlightening. I still have a lot to learn.

VKN: Why do you want to be a writer, Jen? What do you hope to achieve or not achieve with it? If someone were to tell you that the writing life is like a wall made of empty wine bottles, would you still like to do it? For the rest of your life? And, what is the Vietnamese literary landscape like in Melbourne? Is it rich? Semi-arid like some parts of Montana in the States? Or profoundly or profusely indifferent?

JN: Growing up my parents were strict about what I was allowed to watch, even movies and TV-shows rated PG were frowned upon. However, reading was encouraged (because it counted as ‘studying’) and never monitored so I read whatever I wanted to my heart’s content. Growing up, there were many nights I couldn’t sleep, so I read.

Watching the film Spirited Away when I was in my first year of high-school changed how I viewed the world. It was the first time I realised that magic existed: it existed in stories, in people, in the very ordinary and the very extraordinary. I want to create something that can perhaps give rest to the restless, or make someone believe in magic as a possibility, or even just possibility as a possibility.

If someone were to tell me the writing life is like a wall of empty wine bottles I would still do it because you can always fill up the bottles with whatever you like. You can play bowling with the wall of wine bottles. You can hear it crash if you’re bored/frustrated/or simply curious as to what a crashing wall of empty wine bottles might sound like. The possibilities are many and I think writing is like that, even if it is seemingly fragile and empty at first glance. And yes, I want to write for the rest of my life. Or at least, try my hardest in attempting to.

The Melbourne Vietnamese literary landscape is a landscape I’m still discovering, slowly but surely. With the help of publications like Liminal Magazine. Through the writing community on Twitter and locally I’m connecting with more and more Vietnamese writers and more writers of colour every single year. It really warms my heart to think there are a lot more of us here than I initially ever thought possible, especially growing up and thinking it wasn’t possible to be Vietnamese and a writer. I know now it’s possible. Of course it’s possible. Why wouldn’t it be? Why shouldn’t it be? Those are questions I’m asking myself.

VKN: Is being a writer broader for you? You did not state that you want to be just a poet? If being a writer is a broader disciplinary passion for you, what are some of your dreams for your writing life?

JN: For me, I don’t particularly think of one form of writing as being better or more significant than the other. All forms of writing have their purposes. Poetry happens to be the newest form I’m engaging with and I still have much to learn, but I’m loving it so much sometimes I feel like scaling a skyscraper just so I can say to everyone how much I love it. I’m interested in looking at the act of writing as storytelling or as unravelling a line of questioning in an attempt to move towards some kind of answer. Even concluding that there is no answer is about as good an answer as any. My dreams for my writing life varies. Some days I feel very, very ambitious and other days I just want to take a nap in the middle of a lake in the dead of night.

VKN: Since you are still a neophyte in the writing world…if writing doesn’t have to be the primary tool to navigate the world, what would be another passion of yours that you would like to use to move across the Pacific Ocean of Life, Jen?

JN: I’ve been writing professionally for a little over three years, and writing in general (mostly fiction, mostly for fun) for a little over thirteen years, starting when I was 13. I’m 26 now. Throughout my life no matter what changes I was going through writing remained the only constant, which is why in 2016 I decided to become a writer. There are a lot of things I love but nothing I love as much as writing. So, for now, writing is the primary tool I use to navigate the world, and I’m very committed to it.

VKN: If you were to calculate in dog years how long it took for you to put together this chapbook with such an exquisite title, what would that calculation mount to?

JN: When I started writing poetry (and even now) it feels like I’m vomiting up everything inside of me, getting it out without much control of what comes out, and sometimes it splashes up at me from the toilet bowl. It burns my throat. I feel empty and tired and spent. It’s a lot of hard work in a lot of different ways. Afterwards, I need to rest. Before poetry I felt like I was dying a thousand deaths a day. Now with poetry I feel like I’m dying a thousand deaths a day but also I’m being reborn a thousand times too, which is nice.

This chapbook was my first time working on my poetry with people outside of my writing group (West Writers Group based at the Footscray Community Arts Centre, whose existence and support I’m always grateful for). The editorial team at Subbed In (Dan Hogan and Victoria Manifold) were wonderfully warm in their guidance in helping me get my manuscript to where I wanted it. Also, listening to RM’s mono., snacking and napping helped a lot.

So in dog years 4, 444, 444 years.

VKN: Which poem is your favorite from the collection? And, could you break one of your poems down for us? Where were you when you wrote it? How did the poem arrive to you? Which line gives you the most purpose?

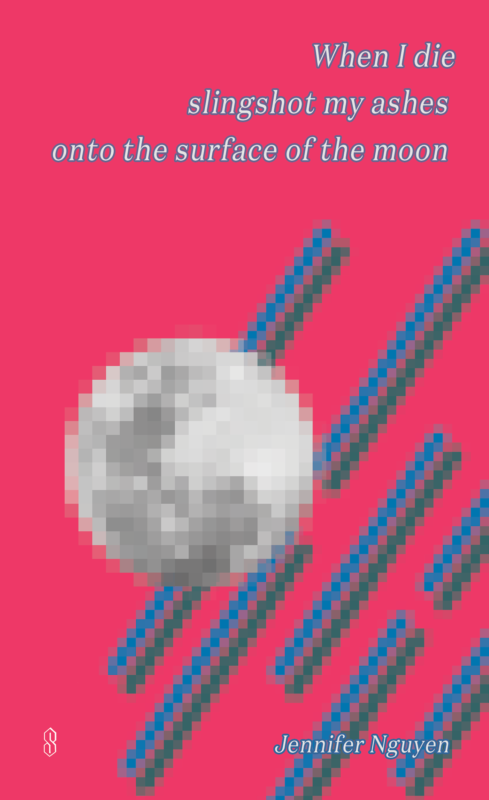

JN: I’ll break down the poem ‘When I die slingshot my ashes onto the surface of the moon’ which is probably my favourite, only because now in hindsight, it takes so much effort to say whenever anyone asks me what my book is called. I have to say it twice or three times, and in a loud venue practically yell my book at a person, which I find terrible and funny and humbling at the same time.

The poem begun to arrive around 5 a.m. It arrived in yet to be ordered lines. It was one of those nights that was quieter than any other night, quiet to the point of unease. I was in bed with my notebook and hour long k-pop playlists on Youtube played, one after another. I could hear the construction of a nearby apartment complex, very mechanical noises: drilling, sawing. I thought about the evening just past and how I went to the supermarket to buy snacks, and on the drive home the moon loomed so full and large I had an intense, ominous feeling of wanting to reach out and climb onto it, but feared I wouldn’t make it, feared falling short and forever falling. The poem talks about ‘When I Die’ in a future tense but for me the whole feeling is a very present feeling. I feel like I’m always trying to simultaneously resolve longings from both my past and future, which leaves me very disoriented. The line that gives me the most purpose is the one about my father putting on lip balm. I’ve never seen him take care of himself like that. And he even bought me one too because he heard me say in passing to my sibling that my lips are so dry. I like to think that’s what poetry is sometimes, giving witness to moments like that.

VKN: Thank you for doing so for us, Jen. What a beautiful process. You wrote in your poem “Soft truths about you & I” that the difference between PAIN and RAIN is a single stroke, what single letter or symbol or number or punctuation mark could you foresee as a door that distinguish you from one world from another, from you from another you? From a poet self to another writerly self? A child from your adult life?

JN: Thank you Vi. It really has been the most tender of processes. For now, I’ll settle on a door that is a question mark that is made up of a lot of question marks that are all oscillating in a way that make it look as if the questionmarkdoor was alive. It attaches itself onto me and I call it my shadow. The shadow travels with me from one world to the next, from my poetic self to my writerly self, from my child to my adult life, and it reminds me to question what I don’t know as well as what I do know. This ‘questioning’ is probably the only thing all these various selves will have in common and the only thing that’ll distinguish them from one another. Life, for all my selves, begins, continues, and has meaning so long as they are willing to engage in questioning the world, the self, and the various phases of life they are currently inhabiting.

VKN: In your bio, you said you write about “ghosts” – Other than a pseudo-ghost such as a cat, do you have a favorite one that you frequently revisits or who frequently visits you? Do you think your relationship with ghosts is celebrated because Vietnamese cultural tends to demand ubiquity with it? Or does your interest for it get born through pure curiosity with the spirited or nebulous world?

JN: I remember family gatherings where adults would drink in one part of the house and the kids would share ghost stories in another. It was mostly the older kids trying to scare the younger ones. I was both scared and fascinated. I’m interested in trying to understand exactly what’s haunting me. A ghost that visits me frequently is the ghost of all my longings saying ‘Look, look at what you want so badly, but can’t have’. I neither like nor hate this ghost, it’s not my favourite ghost, but it comes around often, and I feel it’s importance, as though it’s what drives me to work so hard. I want to raise my fists and get into a fight with it and be like, ‘Well, what I can’t have I’m willing to fight for, so just watch me!’. But also, I realised it’s probably good for us to once in awhile sit down and chat, maybe have a drink, maybe take a nap together.

VKN: What is your least favorite Vietnamese dish? And, why?

JN: I’m actually very fond of Vietnamese dishes and don’t have a least favourite dish. My mother is very good at cooking. My favorites are bún bò huế chay, bánh canh, hủ tiếu, cơm bò lúc lắc, cơm tấm, phở, bột chiên and sâm bổ lượng, to name a few.

VKN: What is your mother like, Jen? Have you been able to use the tool of language to capture her? Like a poetic portrait of her face, for instance?

JN: My mother is the hardest worker I know. So far using language I’ve only been able to capture 1/100th of her. I see my mother’s face by looking at her garden, or in holes in clothes she’s sewn up for me, or in dishes she’s prepared. These are all better at capturing her than I am.

VKN: If one of your poems were to go back to Vietnam as a “Việt Kiều” to visit, where in Vietnam would that poem visit and which poem would that be? And, if your poem were to marry another poem in Vietnam and bring that poem back to Melbourne, which poem from Vietnam would it marry?

JN: The poem I’ll pick is ‘The zebra stripes on the back of the world prove that everything is essential, including you, including me’. The last time I went back to Vietnam I met a well that swallowed up coins. The well was notorious for ignoring wishes. Still. People threw in coins. Including me. I think this poem would try to find alternate universe where the well did grant wishes and empty out its entire wallet.

A poem that’s had a profound effect on me is ‘Someday I’ll love Ocean Vuong’ by Ocean Vuong. There’s so much hope in that one line, that one word alone: Someday. If I can bring forth this hope of ‘someday’ and share it with everyone, that’d be incredible.

VKN: Some of your poems are funny. Especially the last poem from your chapbook and its last four lines. Do you seek out to write funny poems or they just arrive without your permission and you feel doomed and you are compelled to let them live on the page?

JN: I’m always surprised to hear people say my work is funny. I don’t go out of my way to write funny poems. Not much of what arrives, arrives with my permission, which is something I’ve learned to co-exist with. But, I’m always happy to hear that my writing can make people laugh. If joy arrives it can feel free to stay and live on the page. In fact, I hope it blooms and runs rampant.

VKN: Can you talk about dating life and poetry? Do you think they help each other or make it worse?

JN: Dating life? Hahahahahaha. I think human beings are infinitely complex and intriguing and lonely and so determined and so beautiful. I believe rather than deciding whether they help each other or make it worse, they enable endless possibilities, whether they’re operating together or separately, and that in itself is worth everything.

Contributor Bios

Jennifer Nguyen is a Vietnamese–Australian writer, poet and editor. Jennifer’s writing has appeared in publications such as Scum Mag, Ibis House, The Lifted Brow (online), Meanjin (online), among others. She has performed at places such as Melbourne Writers Festival, Emerging Writers Festival and West Writers Forum. Her first book of poems is ‘When I die slingshot my ashes onto the surface of the moon’ (Subbed In, 2019) which was selected as part of Subbed In’s 2018 Chapbook Prize. She is a recipient of a 2019 Wheeler Centre Hot Desk Fellowship and a past participant of Winter Tangerine & Kundiman Online workshop ’To Carry Within Us An Orchard, To Eat’. Twitter @jennguyennifer

Jennifer Nguyen is a Vietnamese–Australian writer, poet and editor. Jennifer’s writing has appeared in publications such as Scum Mag, Ibis House, The Lifted Brow (online), Meanjin (online), among others. She has performed at places such as Melbourne Writers Festival, Emerging Writers Festival and West Writers Forum. Her first book of poems is ‘When I die slingshot my ashes onto the surface of the moon’ (Subbed In, 2019) which was selected as part of Subbed In’s 2018 Chapbook Prize. She is a recipient of a 2019 Wheeler Centre Hot Desk Fellowship and a past participant of Winter Tangerine & Kundiman Online workshop ’To Carry Within Us An Orchard, To Eat’. Twitter @jennguyennifer

Vi Khi Nao is the author of Sheep Machine (Black Sun Lit, 2018), Umbilical Hospital (Press 1913, 2017), the short story collection A Brief Alphabet of Torture, which won FC2’s Ronald Sukenick Innovative Fiction Prize in 2016, the novel, Fish in Exile (Coffee House Press, 2016), and the poetry collection, The Old Philosopher, which won the Nightboat Books Prize for Poetry in 2014. Her work includes poetry, fiction, film and cross-genre collaboration. Her stories, poems, and drawings have appeared in NOON, Ploughshares, Black Warrior Review and BOMB, among others; her interviews with writers have appeared in many publications as well. She holds an MFA in fiction from Brown University, where she received the John Hawkes and Feldman Prizes in fiction and the Kim Ann Arstark Memorial Award in poetry. www.vikhinao.com

Vi Khi Nao is the author of Sheep Machine (Black Sun Lit, 2018), Umbilical Hospital (Press 1913, 2017), the short story collection A Brief Alphabet of Torture, which won FC2’s Ronald Sukenick Innovative Fiction Prize in 2016, the novel, Fish in Exile (Coffee House Press, 2016), and the poetry collection, The Old Philosopher, which won the Nightboat Books Prize for Poetry in 2014. Her work includes poetry, fiction, film and cross-genre collaboration. Her stories, poems, and drawings have appeared in NOON, Ploughshares, Black Warrior Review and BOMB, among others; her interviews with writers have appeared in many publications as well. She holds an MFA in fiction from Brown University, where she received the John Hawkes and Feldman Prizes in fiction and the Kim Ann Arstark Memorial Award in poetry. www.vikhinao.com