diaCRITICS highlights writers, artists, and culture-makers of the Vietnamese and Southeast Asian diaspora. Here, we feature a collective interview with Missing Piece Project’s collaborative team, whose lead organizer is Dr. Kim Tran. This collective interview features seven voices, elaborating on their individual and shared experience of developing and enacting the (re)dedication of their “missing pieces” to create a complex tableau that attempts to recognize and hold space for (as one collective member, David Dang, calls it) “that mixed duality where healing and burdening meet each other. A healing burden.”

To learn more about the Missing Piece Project, you can also read the Missing Piece Project profile post published by diaCRITICS in April earlier this year.

diaCRITICS: As a member of VietUnity and the Missing Piece Project collective, what is the first item of “memorabilia” you wish to bring to the VN Memorial Wall as part of this project to “disrupt memory” and – in effect – “re-member” the Vietnamese presence in this war? And, why is this your first choice of item to dedicate?

What is the second object you would bring? And why?

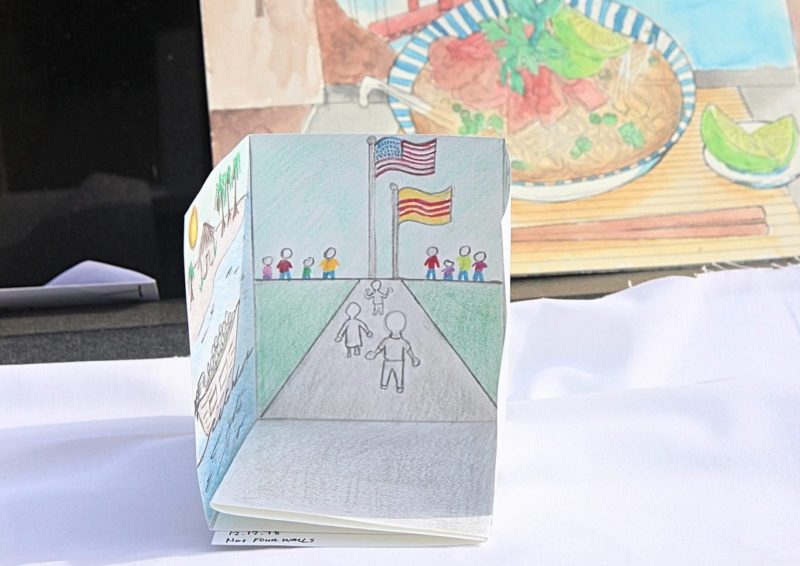

TIFFANY LE: The objects I chose to dedicate at the Wall stemmed from my MFA grad show exploring the missing narratives of my family during their journey after the Fall of Saigon. The dedication of objects together are a collection of small paper boats on a swirling ouroboros illustration, which represented the changing tides and struggles in water. For the boats, each detail in creating them had different purposes: the use of mourning paper money, which is usually burned to send to those who have passed away, as the base for some of the boats are to remember those who did not survive and whose stories we will never know in full; the individual drawings or relief-printings on the boats represent the stories of the people and the items which they carried when escaping Vietnam. For me, the concept of each of the chosen items, or even the lack of any, means that they each represent different stories and how the narratives of the Vietnamese community cannot be condensed to a monolithic experience. The paper boats themselves are metaphoric for the people themselves and the difficulties of their journeys, rather than for the method of transportation, as not everyone left by ships. I feel strongly the need to remember and say through my art that the Vietnamese experience is diverse and many, nuanced to a degree that to understand that presence one has to look at more than one “boat” to have any semblance of understanding. This reason is why I appreciate so many other projects going on like the efforts of Viet Stories: Vietnamese American Oral History Project at UC Irvine, and accessible graphic novels like G.B Tran’s Vietnamerica and Thi Bui’s The Best We Could Do: An Illustrated Memoir. For the 2020 collective dedication, and after my experience with our first dedication in 2018, I hope that I can convey that better (and louder) to a more effective degree so that those who are passing by will linger to read more into our overall project.

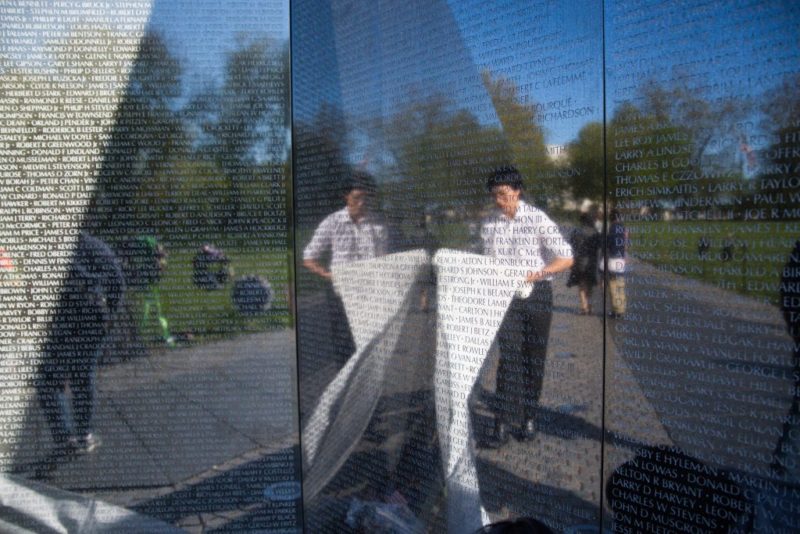

LAN NGUYEN: I dedicated a poem about intergenerational trauma. When I first started seeing a therapist, my therapist asked me if I felt comfortable using the word “trauma” to label my experiences. I quickly responded no, as I thought trauma is something that soldiers and survivors of sexual assault experience, something I was fortunate to have never encountered. Over time, I reflected on my experience and realized that I did indeed have trauma. My tendency to not throw things away stems from my parents’ trauma of thinking that the world may collapse at any minute. My difficulties regulating my emotions stems from a time of war, in which one had to suppress their emotions or it would be too much to handle. My poem speaks of these forms of trauma and was printed using the same font that the names on the wall are engraved in. The background of the poem is granite, the same material as the wall. My choice to replicate my poem in the same way as the wall is designed was intentional, to show that the war not only harmed soldiers, but also generations of diasporic Vietnamese, and that our suffering needs to be memorialized as well.

KIM TRAN: After collecting oral histories with family members, I created several objects/pieces. For the 2018 dedication I burned the names of family members, who had passed during the war, into pieces of bamboo, and created a family tree to show their relations. I also included a piece called “Refugee Fragments: Screenshots of my Ancestors” which were a series of screenshots taken while video-chatting with my grand-uncle in Vietnam from Los Angeles, in which I was able to see my family’s ancestral altar and genealogy records for the first time. In 2019, I brought stones with Vietnamese familial terms/pronouns written on them and invited passersby to place the stones at the memorial. I also sang a Vietnamese folk song (Cò Lả) about a crane flying over green fields, missing/remembering (nhớ) home.

dC: How did you become a part of the Missing Piece Project, and what is your role? What has being part of the Missing Piece Project meant to you? Could you reflect on some of your experiences working on the project?

KEVA BUI: I became a part of the Missing Piece Project through my involvement with Viet Unity-Southern California, the community organization supporting this project. Since the beginning of 2018, I have been a member of Viet Unity-SoCal’s core (leadership board), and when Kim brought up the idea of the Missing Piece Project, it immediately drew my interest. Remembering the American War in Vietnam and Southeast Asia is a complicated affair—it often relies upon different strands of nationalism that elide the experiences of displaced people, marginalized people, and those whose lives did not survive the war. The question arose: how do we hold space for a commemoration of the war that attends to the multitude of different experiences of violence while still remaining steadfast in a critique of U.S. imperialism, militarism, and colonialism that made manifest the conditions for the war to occur in the first place? For me, the Missing Piece Project is so incredibly important because it demands a transformation of memory, a rethinking of how history has rendered the war in Vietnam. As historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot writes in his book Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History, “Each historical narrative renews a claim to truth”—Trouillot highlights how historical narrative emerges through the stories we tell, whether they happen at the family dinner table or exist within the institutional archive. History, in essence, is an amalgamation of stories—unfortunately, it is often just the dominant ones that gain hegemony over how history is narrated more popularly. The Missing Piece Project intervenes into this paradigm, creating space for marginalized peoples to use art, storytelling, and imagination to grapple with our own histories of trauma, displacement, hope, and intimacy—it makes space for us even as we have been pushed to the margins. Working on this project has highlighted the importance of imagination to our work—remembering the past is an imaginative project in dreaming.

DAVID DANG: I became involved in the Missing Piece Project through meeting Kim Tran, project lead, when we attended the Hai Ba Trung School for Viet Organizing 2016, together. I was connected to the Hai Bai Trung School through my time as a Viet Unity LA (now, Viet Unity SoCal) core member. I helped log a lot of the footage and was the editor of the call to action video that was shot by Daniel Luu, Quyên Nguyen-Le, and Lan Nguyen, who I also knew through Hai Bai Trung School when I became a co-trainer, and other Viet progressive-left spaces. Being involved with the Missing Piece Project meant a lot of things for me. The Missing Piece Project gave me a chance to fuse my creativity with social politics and to build and struggle with other Viet progressives I had met in various Viet progressive spaces, in hopes to work collectively towards a healthier community in the Viet diaspora in SoCal, especially since there has been a distance between my family and most of the Viet community, outside of certain friends, for so many years for various reasons.

VIVIAN DUONG: I became a part of the Missing Piece Project by taking an Asian American course at UCLA. Classes that focus on ethnic studies are important because it can play a crucial role in helping others understand themselves and different diverse cultures. Being a part of this project opened a door for understanding and cultural awareness for me. There were new narratives to explore and I was able to engage in dialogues about my community to my family and friends when I came back. This project was very emotional because I never really understood the emotional impact of the trauma my community faced. (Not saying that everyone is a refugee or they had traumatic experiences.) But, being able to understand the different perspectives was enriching for my own personal understanding of my own Vietnamese community.

KIM TRAN: For me, this project has been a good starting off point, a reason, if you will, to start conversations with my family and my larger community. It’s sometimes difficult to ask questions out of the blue about personal histories, especially when there is often so much silence that surrounds trauma. This project has given me a focal point, a kind of doorway into learning and listening, and by way of our collective dedication, a mode of acting out in a tangible and physical way. The weight of this history can feel so heavy – I feel this when I teach the Critical Issues in US-Vietnam Relations class at UCLA. Lecture after lecture, we are discussing difficult topics such as genocide, human rights violations, state-sanctioned violence, racism, displacement, trauma. I found that giving students the option to participate in Missing Piece Project can be a way to help them process this difficult information in a personal/expressive way. For some of them, it’s the first time they are learning this history in a way that humanizes Vietnamese, Lao, Hmong, Cambodian people – since the ways in which the Vietnam War is typically taught in school curriculums doesn’t often afford this humanity to all people involved. Through the project, I think the simple act of making/doing something in the real world can help to stave off a feeling of hopelessness and helplessness when learning about this history. The making and doing centers on the resiliency and strength in our communities today, and insists upon our existence and survival.

dC: The collectivity of the Missing Piece Project is a very integral aspect of the project. As a Vietnamese diasporic artist and writer, I’m also involved with projects of a collective nature; it seems at least somewhat a recurring theme that people of our circumstances and inheritances must in some way address collaboration, polyvocality, and the individual’s role vis-a-vis the collective (whether the reasons for this lay in resisting the western “singular voice” i.e. heroic narratives, or in a desire to heal and reconnect via communal action). To pull a quote from Nothing Ever Dies (a text by Viet Thanh Nguyen that your project statement also references):

“Only sometimes can the past be worked out solely through therapy or individual effort, since the conditions of the past are often beyond the individual, as is the case with war. Given the scale of so many historical traumas, it can only be the case that for many survivors, witnesses, and inheritors, the past can only be worked through together, in collectivity and community, in struggle and solidarity. This effort of a mass approach to memory should involve a confrontation with the present as much as the past, for it is today’s material inequalities that help to shape mnemonic inequities.”

It seems to me the Missing Piece Project is attempting to manifest, via social engagement and art, exactly what Viet Nguyen is speaking about in this quote.

I am curious to know what this collectivity and endeavor of collective action means for each of you. What are the dynamics at play? Are there challenges? Are there successes? Do you feel more or less connected, burdened or unburdened, empowered or healed, or not, etc?

ANTONIUS BUI: To be honest, the Missing Piece Project is one of the first projects that has felt like a true collaboration throughout my artistic career. This is largely, if not completely, thanks to Dr. Kim Tran’s ability to organize and gather us as a collective. I’m learning that true collaboration is challenging, frustrating, and demanding. As a participant who has been unable to attend several meetings last minute, I can’t imagine what it’s like juggling this many schedules and lives. With that said, the trials and tribulations are undoubtedly worth it. I personally feel prouder than ever to identify as a queer Vietnamese-American thanks to the bonds created throughout this ongoing project. Each participant’s lived experience reminds me that there is no singular way to be hyphen American, and that it is our responsibility to constantly define and redefine that for ourselves.

KEVA BUI: Collectivity is absolutely central to the Missing Piece Project—there is no one singular narrative of the Vietnam War. That is the amazing thing about curating a community archive; it reminds us that the War has had an enormous effect on different people but that effect looks differently depending on a person’s situation, context, or experience. Rather than try to prescribe a historical narrative of the Vietnam War, the Missing Piece Project is an archival project that seeks to collect a polyphony of stories that create a historical rendering of a past that has not been forgotten—it is as I quoted from Trouillot before, “Each historical narrative renews a claim to truth.” Each story performs this work—and in the end exposes the inevitable truth, that there is no truth of the Vietnam War. Rather, it is a collection of experiences—violent and hopeful—that assemble together an imaginative memory of the past. History is a collective memory of the past—the Missing Piece Project just ensures that this collective includes and centers the people displaced and most affected by the war and its preceding manifestations and lingering afterlives of U.S. imperialism.

DAVID DANG: We wanted to find ways to welcome all narratives into the discussion of the Missing Piece Project, for people that may be new to exploring themes of trauma of war, while finding ways to be honest about what a lot of our politics were and what the goals were, especially when it came to possible forms of backlash, such as red-baiting. I felt some of these challenges are common in the SE Asian progressive-left diaspora, and some of it was how we were trying to present this project to everyday people in the Viet and SE Asian community with the progressive-left politics we all had, as well as seeing how our own progressive-left politics mixed in with each other, from our own exploration of self-discovery, and how we met each other in that journey.

Building a healthier community in the Viet diaspora meant finding ways to break away from self-destructive narratives that have occurred in the past in the Viet diaspora, and to expand the Vietnam War narrative to acknowledge the ripple effects that oppression imperialism has brought and anti-imperialist resistance and revolution affected the rest of Southeast Asia, including Laos and Cambodia in the global non white-European working community, and to see what direction we can go continuing revolution, as we continue to spiral into fascism on a global scale from a collapsing capitalist economy. Healing to me, meant finding ways to acknowledge who the main root of our past and present oppression has always been; the violent enforcement of private property, whether it was through tribalism, feudalism, colonialism, imperialism, or capitalism. While struggles in the Viet diaspora might not always overlap for various reasons, it has been nice to be able to connect with some of the folx, such as Kim, with processing some of the emotions felt while working on this project. We saw that the project has been part of the overall work that a lot of us see is just part of what we’ve been missing. Working on the Missing Piece Project was another way to continue to pay my dues, or give back, and build with the community, by showing people what I was able to do. I feel that my overall exploration is that mixed duality where healing and burdening meet each other. A healing burden.

VIVIAN DUONG: As someone who grew up in a home where family relationships aren’t so strong and the cultural history isn’t talked about amongst each other – I am culturally rooted by ethnics and traditional familiarity but not by history. The collective nature of this action bridged a piece of my identity that I never really explored, the historical side. It brought a sense of understanding, compassion, and a sense of family for me. The trauma that remained amongst my parents, especially my Dad, left a lingering cold that was contagious. Being a part of this project helped me understand why my parents are the way they are. I understood the cold aura my Dad evoked, the stern voice he had whenever addressing me, and the way he acted when triggered by old memories. I understood my mom’s thought and how she is strongly bounded by traditions. The collective nature of this project allowed me to understand my parents a bit more and become connected to them: understand their actions, understand who they were/are, and understand that they, themselves, are still healing. I was able to learn from other people’s narratives and apply it to my own identity. It was a very emotional experience for me as a Vietnamese American because I felt truly connected to my identity through this project. To be able to see the vulnerability and challenges my community faced and being able to understand those stories allowed me to understand myself better, helping me find my missing piece.

TIFFANY LE: The first dedication revealed a lot of dynamics at play and challenges from the outside audience, which is not as entirely surprising as it is a reminder – the efforts of others trying to co-opt our efforts or even the backlash. However, where there is resistance, I found people who do want to know more, and I found community through the Missing Piece Project after having worked solo for so long. The feeling is weird for lack of a better vocabulary – I feel reconnected to a community, and I feel simultaneously burdened with more work to be done, but also unburdened in that others are sharing the load, too. Overall, this endeavor has been and continues to be a heartening experience.

LAN NGUYEN: The collective nature of this action brought a sense of community and healing for me. The dedication was emotionally difficult, as I shared a very personal poem about my traumas, and seeing the Wall reminded me of the deaths and violence that my people have experienced. Having folks by my side provided support as I processed all of this. The collective nature also shows the diversity of our Vietnamese experience. Our families had different refugee journeys, we all have varying levels of Vietnamese language abilities, we all grew up in different cities. But in the end, we are all Vietnamese and our experiences are in fact, Vietnamese.

KIM TRAN: This collectivity in the Missing Piece Project has felt like an attempt to come home/find home/build home – with all the complexities that that involves. I don’t mean home as a physical space, but rather the relationships and negotiations that need to take place with your family, your people, your tribe, in order to be and feel at home. My family, my history, my ancestors, are such a profound source of inspiration for me, but at the same time are also a source of struggle, pain, and conflict. Maybe I’m not necessarily trying to find home as a collective place of compromise and agreement – but rather I think I’m searching for some form of mutual and collective understanding, despite differences in opinion and perspective. I think that maybe forgiveness will be something important while trying to build this sense of home – a certain kind of letting go, through collective understanding, an understanding of both yourself and of others, in order to be at peace with the past while living in the present, and imagining a future together with a community. A search for and an attempt to build a sense of belonging.

dC: I understand this project in still evolving. What do you, personally, hope to see or want to do next for the Missing Piece Project?

ANTONIUS BUI: What would a memorial created for and by refugee communities affected by the war look, smell, sound, taste, and feel like? Powerful and necessary as our interventions are, our group is beginning to imagine a space of our own, one that isn’t censored by the systems at play.

KEVA BUI: Right now, the Missing Piece Project centers the displaced—largely refugees and their descendants from Southeast Asia heavily affected by the war. As this project grows, I hope we can also grapple with the capacious, extensive effects of the United States’ imperial war in Southeast Asia. How can we extend narrations of history surrounding the Vietnam War in contending with other affected populations across the United States and more transnationally? Can the Missing Piece Project grow to include those voices, to participate in an even more polyphonic remembrance of a war with all too many consequences? How do we grapple with the millions of Black Americans forced to fight in a war by a military draft reliant on the dispossession of individual autonomy? How do we remember the historical solidarities between anti-colonial Black and Asian Americans in the United States and Vietnamese people across the world in resisting U.S. imperialism? How do we think alongside the Chamorro indigenous peoples of Guam, a central staging arena for both the war and refugee camps in its aftermath? Can we connect the imperial, militarized ventures of the United States into Southeast Asia with implementation of statehood in Hawai’i and the denial sovereignty to the Kanaka Maoli people, as their homeland experienced even more increasing militarized occupation in the accruing tension surrounding the Cold War? Indeed, militarized occupation across Asia and the Pacific continued, and in many instances grew, throughout the Vietnam War—including, but not limited to, Guam, Okinawa, Hawai’i, Korea, Taiwan, and the Philippines—and as such, how does memory of the Vietnam War and refugee experiences also tell a story of transpacific militarized empire in the second half of the 20th century? These are questions I think we could possibly grapple with as this project grows, as it transforms into a community archive interested in remembering the war capaciously—resisting and challenging U.S. imperialism writ large.

DAVID DANG: What I’d like and hope to see beyond the Missing Piece Project are more parallels in our struggles connected from the affects of the systems of private property, patriarchy, colonialism, capitalism, and imperialism, globally, archived—which would involve Vietnamese progressive-left minded people meeting with members of other communities such as Indigenous, Latinx, Black, African, and other SE Asians.

LAN NGUYEN: I am personally interested in seeing the Missing Piece Project continue to claim a space for Vietnamese diasporic voices and memories in public spaces, but am interested in seeing the Missing Piece Project move away from the Wall. None of our dedicated items directly criticize soldiers, but rather criticize systems of war and imperialism. I would feel uncomfortable criticizing soldiers at a site that memorializes U.S. civilians who passed in the War, many of them sent against their will, many of whom were from marginalized backgrounds and were against the war themselves. However, by having our dedication at the wall, I feel compelled to self-censor myself and avoid messages that critique soldiers as individuals, out of respect for those who passed. If we had our dedication elsewhere, perhaps people would feel more comfortable talking about the war atrocities that U.S. soldiers committed to our Vietnamese people. Furthermore, why does the Vietnamese diasporic narrative need to be tied to the narrative of the U.S. soldiers? We already see this in history textbooks, which focus on the stories of U.S. soldiers and then add one sentence about Vietnamese refugees as an afterthought. I don’t want the Vietnamese story to be an afterthought added on to the narrative of U.S. soldiers, I want our own section in the textbook, our own memorial, our own space for memory.

KIM TRAN: Since the two pilot dedications were small and organized by members affiliated with VietUnity-SoCal, in the future I would like to see the project be more inclusive of the Cambodian, Lao, and Hmong communities affected by the war, veterans of color, and more broadly, for us to examine the gears that create war and violence beyond our particular histories. As Viet Thanh Nguyen writes in Nothing Ever Dies – even the way we name this war, whether it be the Vietnam War or the American War in Vietnam, makes invisible the experiences of the Lao, Hmong, Cambodian people who participated in and were affected by this conflict. Is it possible for us to see the connections between other manifestations of US imperialism through war and, for example, the state-sanctioned violence against Black bodies in this country, or the violent policies of family separation at our borders? I would like for the Missing Piece Project to be a part of a larger conversation about militarism, imperialism, and state-sanctioned violence, and for us to build solidarity with other groups who are doing work that is connected to ours.

After presenting the Missing Piece Project at a conference this past December at the Vietnam National University of Social Sciences and Humanities, some comments after the presentation changed the way I had been thinking about the project. One comment was from a scholar who made parallels between the work that Missing Piece Project is doing with the work subsequent generations/descendants of Holocaust survivors continue to do in order to remember and learn their histories through museums and memorials. We discussed how the Southeast Asian refugee community does not yet have these public spaces for mourning, remembering, education, and healing. This made me want to do more research into how other communities have commemorated their histories, and perhaps draw inspiration from them – the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama that documents lynchings in the US is one powerful example. Another person at the conference expressed support for the project, but asked us why we gave so much importance and power to this memorial, when it was not designed with our communities in mind in the first place, and was never intended to include us. The person asked, why not create our own framework of commemoration, that could be designed to be more inclusive from the very beginning? Both these comments made me think that we may need to move away from centering the DC memorial, and more towards creating our own space for collective mourning, remembrance, and healing. But how do we imagine/create such a space to be inclusive, and what would this space be like? This is something I hope to work through in a collective way moving forward.

dC: Do you see the Missing Piece Project and your other artistic practices or social activism as being connected? If so, how?

ATONIUS BUI: The Missing Piece Project wouldn’t be what it is without each participating member’s unique background and expertise. As an artist who predominantly plays in hand-cut paper, textiles, and performance, I am so honored to be in conversation with writers, poets, musicians, students, etc. The other members have significantly expanded my way of thinking, allowing me to dream of new ways to engage with audience members beyond my limited artistic practice. Working alongside members like Keva Bui, Tiffany Le, and Lan Nguyen only emphasize how necessary intersectional collaboration is in the 21st century. I would consider Kim Tran’s vision for the Missing Piece Project a model for what art can look like in the 21st century. This project is not only collaborative, disruptive, educational, and socially-engaged, but also loving.

KEVA BUI: Most definitely. As a scholar and community organizer who dabbles in the arts, I see the work I do with the Missing Piece Project as fundamentally connected to all my other work. Historical narration is so fundamentally structured around power—who has the power to speak possesses hegemony over how we remember history. By creating space for historical narration by marginalized people, this project critically shifts how knowledge comes to be sedimented about the war in Vietnam—it demands recognition of the experiences and imagination of displaced peoples affected by the war’s legacy. At the heart of my scholarly and activist work is knowledge—how knowledge comes to be produced and how it structures the machinations of race in subjugating different populations. How can we use knowledge to imagine worlds anew and negotiate the perilous conditions of the inhospitable present? To borrow from Asian American studies scholar Dean Itsuji Saranillio’s book Unsustainable Empire: Alternative Histories of Hawai’i Statehood, “If we think of forms of white supremacy, such as settler colonialism and capitalism, as emerging from positions of weakness, not strength,” we might gain a more accurate understanding of U.S. global empire as a symbol of white supremacy’s fragility. While Sarnillio is primarily discussing Hawai’i statehood and occupation, he offers a compelling framework to view contemporary U.S. empire as also an emergent indication of its vulnerability—and it is from this possibility we might imagine the strength and power of community activism, knowledge production from the oppressed, and, perhaps most importantly, imagination of something new.

DAVID DANG: I always found it interesting that April 30th was sandwiched between the anniversary of the 1992 LA Unrest, and International Workers’ Day, especially the dual relations to those themes in the Vietnamese community, socially, politically, and historically in relation to leftist politics and Blackness. I’d like to see how we as a collective community can come together with other communities of color to further heal and build from the traumas of colonialism, patriachy, colorism, capitalism and imperialism, and their effects on us. I helped connect Kim with local Black Vietnam War Veterans and Black and Asian anti-war activists for insight and some guidance with the Missing Piece Project when I was originally approached by a Black former student organizer from SNCC, on behalf of a Black War Veterans group he was involved with back in 2018. He knew Black Vietnam War vets who had wanted to meet with members of the Viet community to explain and apologize for their involvement with the war, and were interested in making steps towards building a mutually beneficial relationship for our communities to heal from the intergenerational trauma of colonialism, and an imperialist war, that were both similar and different in our struggles.

TIFFANY LE: I do see these as all connected – the Missing Piece Project, my own artistic practices, and social activism. Working as a freelance illustrator means that I usually work more commercially, but for my work overall, I try to be as socially conscious as possible in what I do. I am unable to do what some of my peers do, such as attend city council meetings or rallies, etc., but I try to integrate my art to do the work like design stickers for fundraising for organizations, create zines, do workshops, and participate in galleries. Missing Piece Project has allowed me to exercise a more active artistic approach as well as collaborate with others.

KIM TRAN: Very much so. I feel that they both work in tandem with each other.

CONTRIBUTORS’ BIOS

Keva X. Bui is a PhD student in Ethnic Studies at the University of California, San Diego as well as a member of Viet Unity-Southern California’s core leadership and a participant in the Missing Piece Project. In their graduate research, Keva’s research interests include feminist science and technology studies, transpacific Asian/American studies, militarism and settler colonialism in Asia and the Pacific, and the politics of performance, literature, and aesthetics. Currently, Keva is researching how scientific knowledge production and practices of experimentation in the establishing of U.S. global empire in Asia and the Pacific has shaped the racial and gendered politics of the Vietnam War.

Keva X. Bui is a PhD student in Ethnic Studies at the University of California, San Diego as well as a member of Viet Unity-Southern California’s core leadership and a participant in the Missing Piece Project. In their graduate research, Keva’s research interests include feminist science and technology studies, transpacific Asian/American studies, militarism and settler colonialism in Asia and the Pacific, and the politics of performance, literature, and aesthetics. Currently, Keva is researching how scientific knowledge production and practices of experimentation in the establishing of U.S. global empire in Asia and the Pacific has shaped the racial and gendered politics of the Vietnam War.

David Dang has a bachelor’s of science in visual effects and motion design at the Art Institutes International of MN. The son of second wave boat refugees to Vietnamese/Chinese people in the 80s, and older brother to a younger sister. Originally from Brooklyn Park, MN. Los Angeles Based. Organizer/Activist/editor. Editor of the call to action video for Missing Piece Project. Past work includes editor of “The Story of the Jonathan Jackson Educational Cadre,” along with past post production work for video games, movies, tv, music videos, and commercials. Currently editing another feature length documentary on “The Liberation of Fremont High”, in 1968 and 1969, led by the Black Student Union in South Central LA alongside director/Jonathan Jackson Educational Cadre co-founder, Harold Welton. Socially and politically rooted in the teachings of George Jackson, Black August, and Malcolm X.

David Dang has a bachelor’s of science in visual effects and motion design at the Art Institutes International of MN. The son of second wave boat refugees to Vietnamese/Chinese people in the 80s, and older brother to a younger sister. Originally from Brooklyn Park, MN. Los Angeles Based. Organizer/Activist/editor. Editor of the call to action video for Missing Piece Project. Past work includes editor of “The Story of the Jonathan Jackson Educational Cadre,” along with past post production work for video games, movies, tv, music videos, and commercials. Currently editing another feature length documentary on “The Liberation of Fremont High”, in 1968 and 1969, led by the Black Student Union in South Central LA alongside director/Jonathan Jackson Educational Cadre co-founder, Harold Welton. Socially and politically rooted in the teachings of George Jackson, Black August, and Malcolm X.

Tiffany Le was born and raised in the Little Saigon area of Southern California. She is a Vietnamese-American freelance illustrator who investigates themes towards cultural legacy, comparative mythology and literature, and social topics through an Asian American lens.

Tiffany Le was born and raised in the Little Saigon area of Southern California. She is a Vietnamese-American freelance illustrator who investigates themes towards cultural legacy, comparative mythology and literature, and social topics through an Asian American lens.

Dr. Kim Nguyen Tran is an arts educator, ethnomusicologist, and community organizer based in Los Angeles. Kim teaches in the Asian American Studies Department at UCLA and in the Music Department at Glendale Community College. She is resident ethnomusicologist for the arts organization Bridge to Everywhere (www.bridgetoeverywhere.org) and leader/participant of the Missing Piece Project (www.missingpieceproject.org).

Dr. Kim Nguyen Tran is an arts educator, ethnomusicologist, and community organizer based in Los Angeles. Kim teaches in the Asian American Studies Department at UCLA and in the Music Department at Glendale Community College. She is resident ethnomusicologist for the arts organization Bridge to Everywhere (www.bridgetoeverywhere.org) and leader/participant of the Missing Piece Project (www.missingpieceproject.org).

Antonius Bui (they/them) proudly identifies as a queer, gender-nonbinary, Vietnamese-American artist. They are the child of Paul and Van Bui, two Vietnamese refugees who sacrificed everything to provide a future for their four kids and extended family. Since graduating with their BFA from the Maryland Institute College of Art in 2016 , Antonius has been fortunate to receive fellowships from the Vermont Studio Center, Kala Art Institute, Tulsa Artists Fellowship, Halcyon Arts Lab, Houston Center for Contemporary Craft, Yaddo, The Growlery, Anderson Center, and Fine Arts Work Center.

Antonius Bui (they/them) proudly identifies as a queer, gender-nonbinary, Vietnamese-American artist. They are the child of Paul and Van Bui, two Vietnamese refugees who sacrificed everything to provide a future for their four kids and extended family. Since graduating with their BFA from the Maryland Institute College of Art in 2016 , Antonius has been fortunate to receive fellowships from the Vermont Studio Center, Kala Art Institute, Tulsa Artists Fellowship, Halcyon Arts Lab, Houston Center for Contemporary Craft, Yaddo, The Growlery, Anderson Center, and Fine Arts Work Center.

Lan Nguyen is second-generation Vietnamese American from Long Beach, California. She received her Bachelor’s of Science in Education and Social Policy at Northwestern University. For Lan’s MA capstone project at UCLA in Asian American Studies, she is creating a documentary about Vietnamese refugees impacted by deportation and the systemic factors that lead to the criminalization and statelessness of Vietnamese refugees. She is involved in progressive Viet activist communities in Southern California and is also involved in inter-ethnic anti-deportation work. She is a 2019 NeXt Doc Fellow. In her free time, she enjoys running, photography, and hanging out with her rescue dog!

Lan Nguyen is second-generation Vietnamese American from Long Beach, California. She received her Bachelor’s of Science in Education and Social Policy at Northwestern University. For Lan’s MA capstone project at UCLA in Asian American Studies, she is creating a documentary about Vietnamese refugees impacted by deportation and the systemic factors that lead to the criminalization and statelessness of Vietnamese refugees. She is involved in progressive Viet activist communities in Southern California and is also involved in inter-ethnic anti-deportation work. She is a 2019 NeXt Doc Fellow. In her free time, she enjoys running, photography, and hanging out with her rescue dog!

Vivian Duong earned her bachelor’s of arts degree in Psychology with two minors, Education Studies and Asian American Studies from the University of California, Los Angeles. She was born and raised in the South Bay of Los Angeles. She’s a proud first-generation Vietnamese American who uses her free time volunteering and participating in the community. She loves community work and is actively learning about various issues to work towards empowering, bettering, and teaching a community. As a recent graduate, she is interested in pursuing a career in Student Affairs in Higher Education to bring in more inclusive programming in Higher Education environments or be involved in community health. Moreso, she is interested in cultural competency services and the issue of Mental Health in Asian American communities. In her free time, she enjoys writing songs and poetry.

Vivian Duong earned her bachelor’s of arts degree in Psychology with two minors, Education Studies and Asian American Studies from the University of California, Los Angeles. She was born and raised in the South Bay of Los Angeles. She’s a proud first-generation Vietnamese American who uses her free time volunteering and participating in the community. She loves community work and is actively learning about various issues to work towards empowering, bettering, and teaching a community. As a recent graduate, she is interested in pursuing a career in Student Affairs in Higher Education to bring in more inclusive programming in Higher Education environments or be involved in community health. Moreso, she is interested in cultural competency services and the issue of Mental Health in Asian American communities. In her free time, she enjoys writing songs and poetry.

~

Learn more about how to get involved at: missingpieceproject.org/about/

[…] can also read more on diaCRITICS about The Missing Piece Project in this collective interview and this project profile (featured in honor of last year’s April […]