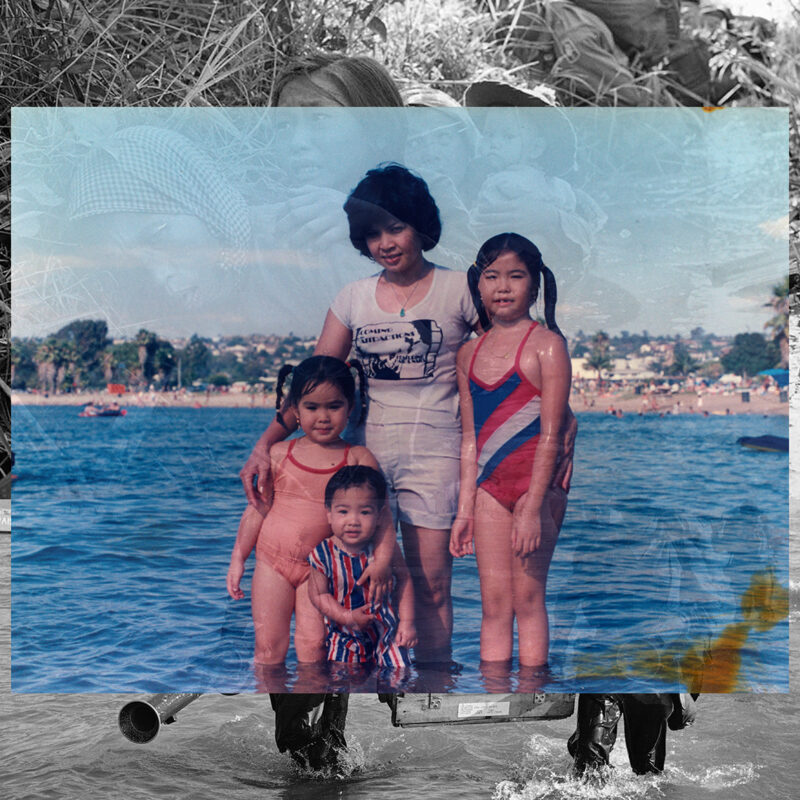

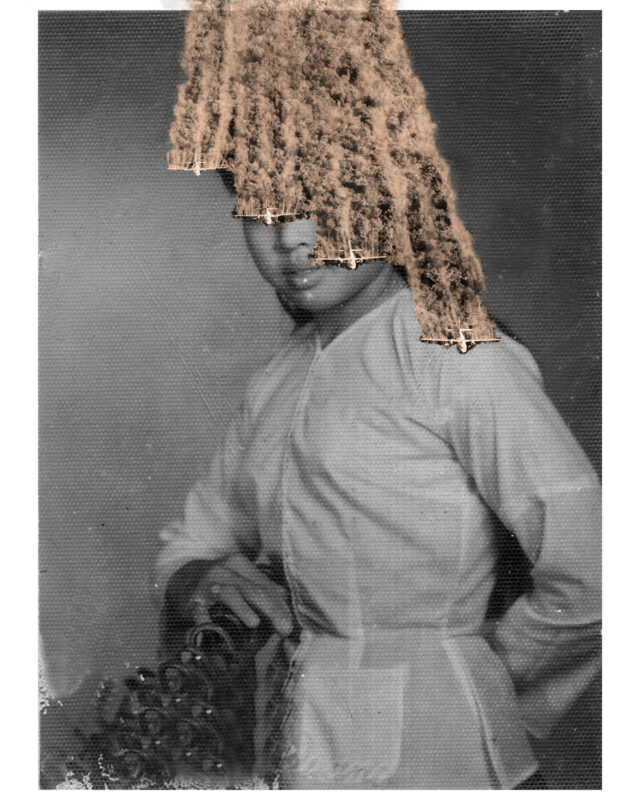

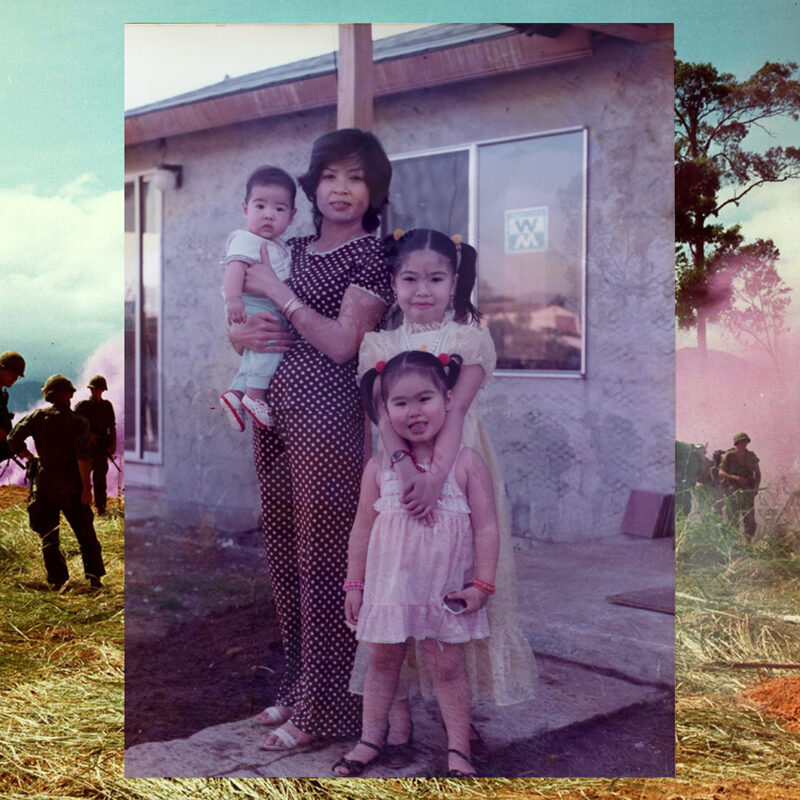

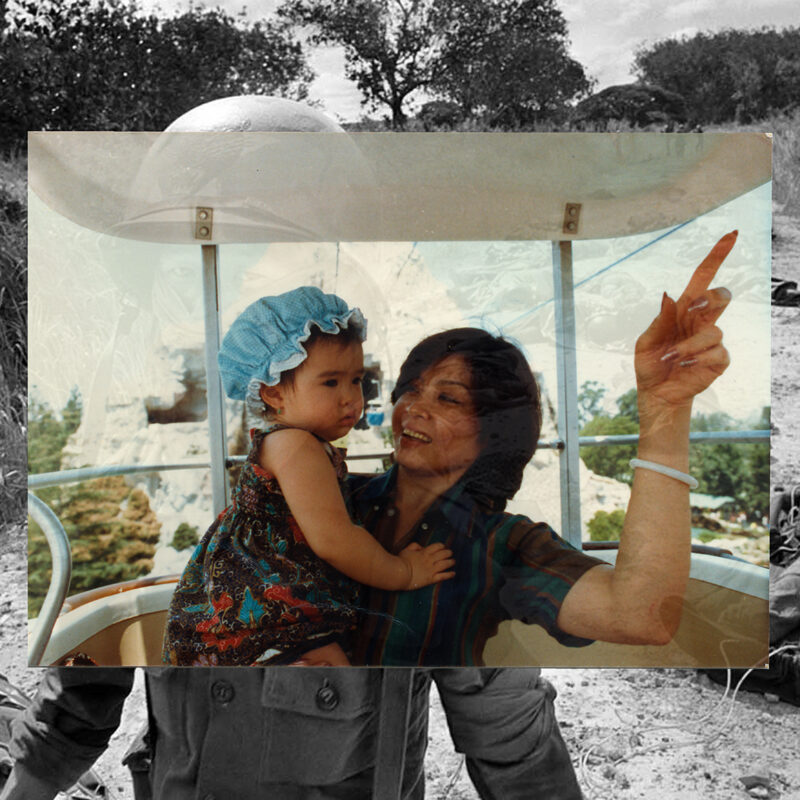

Between Home and Here (2019) is about death in life, life and death, hardness and softness, and a distinct shift between a gothic romance and poetic darkness. It touches on migration, immigration, refugees and immigrants. Pairing imagery from the Vietnam War (hands) and flowers, women and child soldiers with dense jungle foliage as representation and narrative of the people and family directly involved, and the generational trauma that follows.

Ann Le’s World Wars series (2019) layers documentation of families, soldiers, and individuals in Vietnam during the war with family photographs of her own mother and siblings. The cumulative effect of this imagery evokes the importance of personal and collective remembrance. By digitally rebuilding temporal and historical disruptions, Le comments on the idea of home, displacement, separation, and how we embrace and conquer loss. Le’s tragic and poetic composites unravel narratives and place her Vietnamese American perspective into a contemporary landscape.

Artist Statement

The essence of my work is the search for narrative within my language, and the understanding of the duality of my Vietnamese – American-ness.

Ann Le in conversation with artist Nazish Chunara.

Nazish Chunara: What information are you looking for when you research in preparation for a body of work?

Ann Le: When an idea comes, I entertain the idea by cycling through it as a narrative; what is the story line? The work usually stems from a more subjective and emotional, personal space. An idea can trigger from looking at old family photographs, films, art, and poetry. I then look for factual information found online, or in books. I correlate that found and researched information with my initial idea. Let it be a personal family narrative and the events of the Vietnam War, for example. The visual elements form once I have enough information.

What memories are you recalling, yourself, to share in your work?

Depending on the work, I am recalling my childhood memories growing up as a first generation Vietnamese American to immigrant parents. To shared collaborative memories from stories retold by my mother, father, and or sister. I am creating a fiction / non-fiction of events that have occurred in our history. Memory is slippery.

You are both pulling apart and piecing together images in your art. What drew you to this method of creating?

It started off as a practice to force myself to instantly see the work, to make more work quickly. It’s an accessible approach to making and seeing the work, and creating a specific narrative. By deconstructing and constructing the narrative, the story line, I am in control of my message and how I want it delivered. My influences are surrealism and collage, minimalism and conceptual art. I have adapted these styles into my work. In my undergrad studies, I came across Rene Magritte’s works and was mesmerized by the anonymous and his perceptions of reality. By breaking apart my image I am capturing an essence and philosophy for a special engagement. Through investigation, I bring the visual information together to create language and dialogue.

What sort of artificial stories are you creating to mingle with the history you learn about?

Memory is a retelling of what we think we remember; it’s a collaboration of events and collected moments that have occurred in the mind. In my work Home, I recreated a series of faux family portraits. I scanned in old family portraits of my relatives from Vietnam, and paired them with images of family homes I photographed throughout Los Angeles. By doing this, I am fabricating a substitute family photo album – thinking of the many displaced families, and individuals that have escaped in search of asylum. The language in my work touches on separation and bridges the question of what came before, and what’s to follow.

Do these stories alter your perception of your family’s culture?

Yes most definitely. I didn’t realize how important family gatherings were prior to visiting Vietnam for the first time in 2005. Being first born in San Diego, I grew up with my parents, older sister, and younger brother. My parents were the only ones that left Vietnam after the fall of Saigon. I didn’t grow up with grandparents, aunts, uncles, or cousins. Although my parents created friendships within the Vietnamese community in San Diego, I didn’t connect with that community. My parents have yet to fully assimilate, while us kids Americanized to what we only knew growing up in the urban inner city of San Diego. It was a strange duality to be in the in-between space of being both Vietnamese and American.

Do they break them down in any way to better visualize a history?

The break down helps me better visualize what has happened to a country after a war. The deconstruction and reconstruction helps me to understand the many that were and still are displaced and separated. It also shows the desperation of humankind to survive.

How has learning about your family and culture affected your perception of the relationship between the eastern and western worlds?

My work significantly narrates my family’s traumatic decision to migrate in search of freedom and allowed me to immerse myself in the history of my native country. It’s a backdrop that merges the identities of East and West, bonding cultural and political views of the war. By pulling collective memories together, I am transmitting another’s memory, and reconstructing my own projections. This act of revisiting my family’s journey has allowed me to recognize, appreciate and articulate the unexpected gifts that their migration to the U.S. has brought me.

I can feel the sacrifice your family made, in your work. In your process of exploring your family’s history, do you feel that they lost a part of themselves or left behind an identity?

Yes I feel they have lost + left behind a great deal when they got on the boat that evening. There are vast amounts of sadness and longing for our family across the ocean. Old photographs help my parents relive their younger selves. Although there was a part of them that was lost, the future they have provided for us has become rich in experience. It’s bittersweet. My parents would not have stayed behind in Vietnam with that type of dictatorship in charge. I can see where I get my strong-willed attitude. In Nathalie Huynh Chau Nguyen’s book Memory is Another Country, she shares that, “The act of remembering is a means of bringing the past alive, and an imaginative way of dealing with loss. For refugees, memory acquires a particular power and poignancy, since the country that they remember is now lost to them.”

How has developing your work affected your own identity, as an artist, as first generation American?

I’ve become much more curious; I ask more questions to figure out the why’s and how’s. The visual language I’ve developed thus far has formed my true self in this present moment. There is more honesty + vulnerability in my work. As an artist, I have to leave behind the, “ is it good, does it look good?” Good or bad, the engine is running, and there’s a language. Although I don’t feel the pressure of being first-born generation American, there’s an underlining preconception to be pressured. Being Asian American and going into the Arts is taboo, so I’ve been told. There are barriers to be broken, I always tell my students, “Learn the rules like a pro, so you can break them like an artist.”

How have your parents responded to your work?

There is a definite language barrier when it comes to the poetics of my work. My parents aren’t well versed in English, and I the same with Vietnamese. My father was a portrait photographer in Vietnam, so he critiques the technical aspects of my straight photography. But we don’t delve into the essence of conceptual fine art. My mother questions my approach of covering the skin of a portrait with wallpaper, or my tactics of cutting into the print. She’s not sure why I would “ruin” a perfectly good image. They know that I work with visual imagery, but still question my motives on why I do what I do.

What advice do you have for emerging artists?

Do work, whatever it may be. Researching, note making, sitting in your studio space thinking of making the work. It’s all a part of the process. Make more, so you can fail more. Once we fail, we get to the good stuff. I think many people stop when they hit the wall, rather than embracing the wall. Watch more films, see more art. This can randomly trigger inspiration and ideas. Bring a small notebook, I try to jot down my ideas right when they hit. Don’t worry about what others in your field are doing; yes, make note, but don’t compare. It’s okay to make ugly work, if the idea is there, the work visually overtime will form into itself. Live with the work, print the work out and pin it to the wall. Edit, edit, edit – the first draft of most things is shit.

In addition, what my mentors in college have said: “It’s not hard, just make the work, you’re not going to die” & “See what’s popular, take a look at what’s happening in the galleries, then go the opposite direction”.

Shows:

January 7 – March 24, 2020

Reconstructing Slippages in Time: Between Home and Here (solo show)

UCSB Multicultural Center

494 UCEN Rd Room 1504, Santa Barbara, CA 93106

March 13 – June 7, 2020

We Are Here: Contemporary Art and Asian Voices in Los Angeles (group show)

USC Pacific Asia Museum

46 N Los Robles Ave, Pasadena, CA 91101

April 18, 2020, 2:30 PM

Artist Gallery Talks (artist discussion)

USC Pacific Asia Museum

46 N Los Robles Ave, Pasadena, CA 91101

May 16, 2020, 6:00 PM

Conversations@PAM: Southeast Asian Refugee Narratives

USC Pacific Asia Museum

46 N Los Robles Ave, Pasadena, CA 91101

Author Bio

Ann Le has always dealt with identity, culture, family history, and the duality of becoming Vietnamese-American in her work. Inspired by the cultural contexts in her life, she correlates the artificial with remembrances of generational trauma. Sentiment is vital in her works as she questions her personal experiences to construct imposing art. She excavates her lineage by revisiting her family’s experiences by using personal and found images to reconstruct slippages in time and history. As layers of images are stacked upon one another, Le travels through time commenting on the idea of home, displacement, separation, and how we embrace and conquer loss. Tragic and Poetic composites are pieced together to unravel narratives which places her Vietnamese-American perspective into a contemporary landscape. Ann Le was first generation born in San Diego, CA and currently lives and works in Los Angeles.

Ann Le has always dealt with identity, culture, family history, and the duality of becoming Vietnamese-American in her work. Inspired by the cultural contexts in her life, she correlates the artificial with remembrances of generational trauma. Sentiment is vital in her works as she questions her personal experiences to construct imposing art. She excavates her lineage by revisiting her family’s experiences by using personal and found images to reconstruct slippages in time and history. As layers of images are stacked upon one another, Le travels through time commenting on the idea of home, displacement, separation, and how we embrace and conquer loss. Tragic and Poetic composites are pieced together to unravel narratives which places her Vietnamese-American perspective into a contemporary landscape. Ann Le was first generation born in San Diego, CA and currently lives and works in Los Angeles.

IG: @annsgood

annle.net