“We are all great pretenders…”

Before the film Bohemian Rhapsody came out, I didn’t know that Freddie Mercury’s name was Farookh Bursala. One of my favorite scene in this movie is when he introduces his girlfriend Marie and his mates from the band to his family. Everyone is astonished because his parents are using his real first name, Farookh. Freddie/Farookh is angry. He says that from now on, he should be called Freddie. It’s not only a “stage name”, but it’s also now his official name, on his passport, he repeats. Very coldly, the father then says to his son, What a shame to change your own name.

There is so much in a name. In Fall 2018, a controversy about first names inflamed the media in France. Eric Zemmour, a well-known editorialist, insulted Hapsatou Sy, a black woman, on television telling her that her first name was “an insult to the Republic”. “You should be called Corinne, that would suit you well,” he added. For Zemmour, so-called “good immigrants” were supposed to give “French names” to their children to prove they loved their new country. As Marine le Pen, the head of the far-right party, who was Emmanuel Macron’s contender in the presidential election in 2017, has said, “La France tu l’aimes ou tu la quittes.” France, you should love it or leave it.

I was leaving for Morocco for work and in the airport, scrolling on Twitter, I first heard about this controversy. On the plane, I couldn’t stop being angry. I hurriedly wrote an Op-ed for the newspaper I work for. “Please, Mr. Zemmour, leave our first names alone.” By this “us” I meant all people who happen, like me, to have first names which point to their (non-French) origins. Worst of all, I even alluded to the fact that I had proudly given my daughters, who are Eurasian, Vietnamese first names. The op-ed was published quickly on the website of my newspaper. I was insulted on Twitter and on Facebook. People said that my reaction proved that Zemmour was right. I didn’t want to melt into “la Republique Française”. Fortunately, other people also thanked me for saying out loud how they had also felt insulted by what Zemmour had said. It was hard for me to explain to my friends or colleagues why I was so mad. A lot of journalists I considered “allies” disapproved of that op-ed. They told me I had fallen into the trap of feeding the troll, by giving my attention to this guy. It was easy for them, being white: they were not the ones being insulted.

I realized that this issue of first names was touching something very deep inside of me. I was born in France from Vietnamese parents who had immigrated just before the Fall of Saigon. I grew up in Le Mans, a city in which we were one of the first Asian families to settle. Everyone had a first name and a last name which sounded perfectly French and simple. In this middle-sized town, we stood out. Our faces. Our food. Our names. We had weird names divided into three parts and not two. If I were to introduce myself in Vietnam, I would say I am Bui Doan Thuy. In Vietnam, the first name comes last and the last name comes first. It’s interesting when you think about it: it means the family you belong to comes first, well before your own self. It’s very Asian. And quite confusing for Western people who don’t know in which order they should put the Asian names. I make the mistake too.

For a long time, Vietnamese people didn’t have first names for me. Everyone was Tonton or Tata (uncle, aunt). Sometimes they would even be called by numbers: Chi 7, Chi 6 (Sister 7, Sister 6). I didn’t even know my own parents’ real first names. My mother was sometimes called Chi 6, sister number 6, or Jeanne, a French first name – a heritage of colonization. In her school they used to sing “la Marseillaise”, they learned French history, and Vietnamese was learned as a foreign language. That’s why she was given a French first name, still used in her family. But this first name, “Jeanne”, was not the name on her passport. The first time I saw her real Vietnamese first name, Huynh Anh, on her passport, it sounded unfamiliar to me.

My father is named Bui Anh Dung. Vietnamese people would call him Dung. With the Vietnamese southern accent, it sounded something like “young”, very different from the northern accent which would be “zoung” . When talking to French people, though, my father would say, “Call me ‘zoum’.” Zoum. I thought it was a ridiculous nickname. A Teletubbies name. It took me a long time to understand that this was his way to “French-ize” his first name . As a child I would’ve preferred him to be called Patrick or Eric, like all other white fathers I saw at school. I wanted badly for him to speak French without his heavy Vietnamese accent. I was ashamed of his being different from the other fathers, I was ashamed when he talked very loudly in Vietnamese in the streets, and when people would stare at us. Later, I would be ashamed for having been ashamed of my father.

My name says where I come from. It describes my lineage. Bui is the last name of my father. Doan is the last name of my mother. Thuy is my first name. When speaking Vietnamese, my parents used to call me “Thuy”. But, at school, I was called Doan-Thuy. My name was such a curse in those times. No one could say it properly. No one could spell it. No one could remember it. For a long time, I wanted to be called Stéphanie or Marie. I had this obscure feeling that for French white people, we, Asians, formed an indistinct magma, with unrecognizable faces, unpronounceable names. My only identity was to be Asian, with this weird name people never remembered, this face people would confuse with another Asian face.

When I turned twenty, I decided to change my first name: I split it in two. I was Doan Thuy, I became Doan. It was like having a double life. Being a spy. Abandoning this girl that I was in the past, to transform into a new one. My family would keep on calling me Thuy in Vietnamese, Doan Thuy when talking to me in French. In college, the new people I met called me Doan. I guess I was hoping to reinvent myself being Doan, as someone better, more attractive, more charismatic and popular, as I had always felt I didn’t belong. Let’s be honest. It didn’t work. In my prom, there was another Vietnamese girl named Anh-Do. Everyone kept on mistaking us. Do-An, Anh-Do, pretty much the same, huh? Those years, at college, were dreadful. I only felt like I was myself with people calling me Doan Thuy. With my family. Nonetheless, I stuck to Doan. When I started to work as a journalist, I signed my first article as Doan Bui. I was very proud to see my name in a newspaper. Writing was something I thought was not meant for people like me, people like us. People who never were in the books, either inside the pages, or outside, on the covers. I became Doan Bui, this person who uses words, who makes a living out of it, who writes in French, which was finally the most desired way of becoming “French”, for me.

There is just a slight problem: my sisters are also called Doan. In my family, in short, there are four Doan Bui. As if we were sharing the same identity. Sometimes it can be weird. For example: when my sister’s new boss googled her and found my publications as a journalist, and wondered whether my sister had a double life. Family travel can also be quite funny when you see the face of the lady checking us in at the airport, as she realizes we are all called Doan Bui.

*

In the wonderful novel by Jhumpa Lahiri, The Namesake, the hero, born in the US from Bengali parents who immigrated there, is called “Gogol” by his parents, the first name his father chooses because of his love for the Russian author. When the boy grows up, he begins progressively to hate it. So he changes it for his official first name, which is “Nikhil”, and can very conveniently be shortened in “Nick”. Jhumpa Lahiri writes wonderful passages about the distinction between “pet names” and “good names”:

In Bengali the word for pet name is daknam, meaning, literally, the name by which one is called, by friends, family, and other intimates, at home and in other private, unguarded moments. Pet names are a persistent remnant of childhood. (…) These are the names by which they are known in their respective families, the names by which they are adored and scolded and missed and loved. Every pet name is paired with a good name, a bhalonam, for identification in the outside world.

Jhumpa Lahiri describes so accurately my own struggle with my names, between my “pet name” Thuy and my “good name” Doan. Gogol-Nikhil felt the same as I had, towards his name and origins. His name is “an entity shapeless and weightless, [that] manages nevertheless to distress him physically, like the scratchy tag of a shirt he has been forced permanently to wear.”

Jhumpa Lahiri is brilliant in depicting our double lives, our double identities, our close relationship towards family and the different relationship to the outside world. Especially to the opposite sex. When Gogol dates girls, white girls, he has to be Nikhil. He’s not capable of dating AND being Gogol. At the end, Gogol finally hooks up with Moonshomi, a Bengali girl born in the US, whose parents are acquaintances of his parents. It’s the first time he dates a woman who has known him by his real name.

I met the person who would become my beloved husband and father of our daughters in that period when I was changing names. He has always called me Doan-Thuy. I would have stripped his eyeballs off if he had called me Doan. I wonder what would have happened if I had met him later, when I was “Doan”. When I got pregnant in 2005, I wanted our daughter to have a Vietnamese first name that tells about my origins, my lineage, her heritage, as her last name is “typical” French. I had to surf on the Internet to find a Vietnamese first name that would be lovely and easy to pronounce. After my daughter’s birth, though, I realized it was not so easy for people to remember it.

When I was pregnant with my second daughter, in 2007, the mood had changed. The president, Nicolas Sarkozy, obsessed with French-ness, had even created a “ministry for national identity” to define it. It was a very strange time. I had lost my ID, and when I wanted to renew it, I was asked to prove I was French: it took me nine months to do the paperwork. I felt like Joseph K in “The Trial”. Officials would stare at me and speak to me very slowly, as if I didn’t understand French: they thought I was a Chinese illegal immigrant. I realized then how easy it was to be on the other side. As a journalist I had interviewed so many illegal immigrants, telling stories of their struggles and their shame, but I always had that egoistic and comfortable feeling that I had nothing to do with them. Just because my parents had arrived earlier.

At the same time, one of my Viet-Kieu friends was also expecting his first child. This friend had changed names when he started to work. “Having a foreign-sounding name is a burden, a curse. Remember our childhood! You shouldn’t pass this on to your children. You don’t want them to be discriminated against,” he told me.

When my younger daughter was born, I had second thoughts in the hospital. I stuck to the Vietnamese first name I had chosen with my husband, but I decided she needed another first name, a French-sounding one, just in case. We picked up “Ariane” out of nowhere: we hadn’t prepared it… “Ariane” is written on her passport. But we never used it. Once, she asked me about it. I felt stupid.

*

“You should be ashamed to change your name,” says Freddie Mercury’s father. I didn’t take another first name, like Corinne or Stephanie. But I realized I have still abandoned my real first name. The one I severed, so long ago. Doan Thuy. My real first name. I long for it sometimes. It’s like a phantom limb. Like a tooth that has been removed but is still pulsing in my mouth. I love the way it sounds. Like those old songs you used to listen to during childhood or as a teenager. I love that my loved ones still use it. I prefer it to the first name I use in my everyday life: Doan.

But maybe life goes on like this. We put on a mask, we play our role in the never-ending comedy that is life, but deep inside we know we are not reduced to that mask. Doan is my mask, the mask behind which I hide, but I know I am Doan Thuy. I write as Doan, but it’s not the real me. In The Namesake, Gogol grows old. He gets married, then divorced. But he keeps on being called Nikhil. All the way through the novel, though, the narrator calls him Gogol. Like it is his secret self. Freddie Mercury’s favorite song was “The Great Pretender”. Farookh was hiding behind Freddie, the flamboyant performer, loving all those disguises and masks. As Ziad, a great fan of Freddie Mercury, who arrived in France when he was 6, told me: “He fascinated me because he had managed to create his own identity, out of nowhere.”

Yes, maybe we all need masks. Maybe we are all great pretenders. Especially us children of immigrants. We are endlessly pursuing this magnificent delusion: being perfectly French. We are like Odysseus, playing with our disguises. In a never-ending journey. At the end Odysseus finds his way back to Ithaca. I guess we also know that in this intimate journey, something is expecting us. Home. Nha. It’s not a place. It’s inside us.

AUTHOR BIO

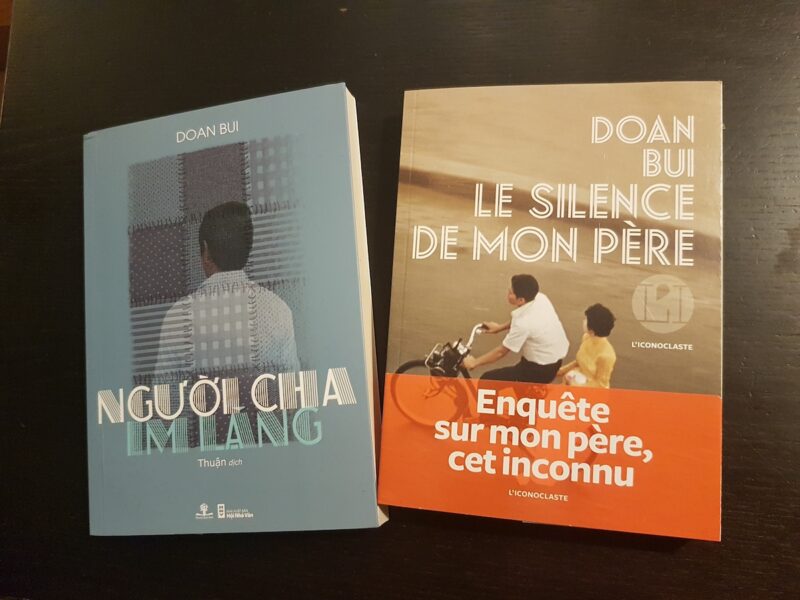

Doan Bui is a French journalist and writer, born from Vietnamese parents. In 2005, her father had a stroke and became aphasic. Eleven years afterwards, she published in 2016 “le Silence de mon père” (the silence of my father) – Editions Iconoclaste- a literary quest to find her father’s story, now that he doesn’t have the words to tell it anymore. Le silence de mon père received several awards (Prix littéraire de la Porte dorée, Prix Amerigo Vespucci). Le silence de mon père has also been translated in Vietnamese (Phuong Nam Books). As a journalist, Doan works for le Nouvel Observateur and was awarded with the Prix Albert Londres in 2013 for a story about refugees.