Trần Thị NgH is a writer, classical pianist, music teacher, and a painter. A multi-faceted talent whose expressions are not confined to one medium, nor to one citizenship–she holds residences in both Saigon/HCM City and Paris, France. A writer of the first-generation whose work has been published in the diaspora as well as inside Vietnam, she abides fluidly in-between. diaCRITICS editor-in-chief Dao Strom visited with Trần Thị NgH in her home in Saigon in January 2020. To introduce diaCRITICS readers to the uniquely spirited and playful work of Trần Thị NgH, we share here a translation of one of NgH’s short stories, “Deviate” (“Lệch Một Khấc“), originally published in Saigoneer.

~~

“Deviate”

Translated by Paul A. Christiansen & Thi Nguyen

– Have you finished any new paintings recently?

– A…number, good output.

– Can I come over to see the paintings some time?

– If the paintings get seen but not sold then…ư…ư…

– That’s better than the ones that buy but don’t know how to see them.

– I’ve never sold paintings to blind people.

– But blindly sold them to rich people?

– If you need money that much, why not find something else to do instead of scribbling for the-blind-yet-rich?

The mobile phone screen remains silent without a reply.

Ten minutes later, té tẹ tè te. He texted:

– OK

The negotiations failed for the one who wants to see the painting. OK means he finally understood the message.

It’d been a long time since he last went to Nhu Thị’s hermitage to see Đĩ Đực and then, driven by hormones, not situation, seduced the painter in the very room the painting was hung. Are men cursed or what! God created woman from man’s rib, which makes men run around unceasingly searching for the bones they’ve lost. Some, despite living happily with the bone they’ve found, still greedily chew others. He had remarried, and even though he’s a sexagenarian, still wore bright floral shirts with bird patterns and roamed around obeying his testosterone. Spurned by Độc Cô Cầu Bại, he decided to escape somewhere to recover from his injury. Once he thought the old wound had grown new skin – although it irritated him for quite some time before it finally started to heal – he tested the waters through a text message: Recently…

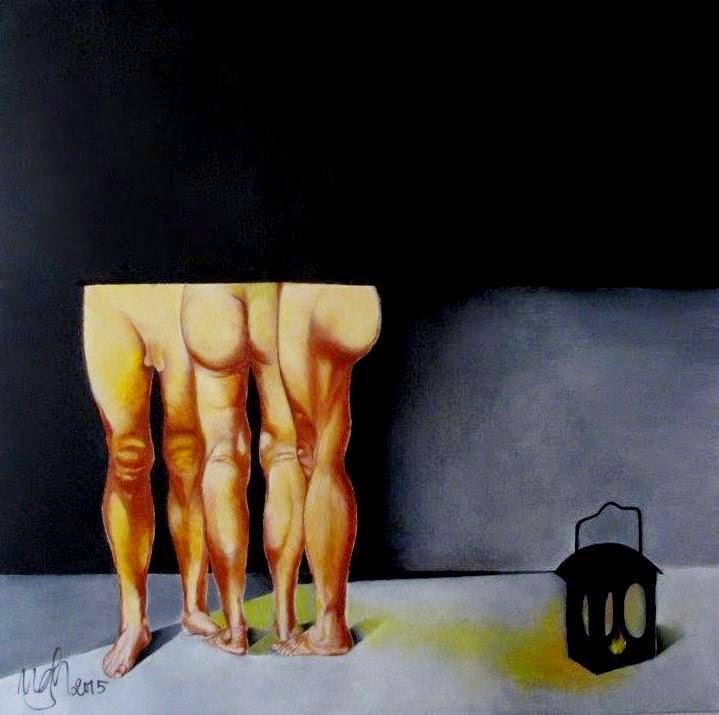

Whenever there’s a touch of eroticism in a piece of artwork, the appreciator will consider the artist as deviating towards sexuality. Đĩ Đực is a human anatomy beginner’s practice exercise; oil paint on canvas based on basic instructions offered by several pencil sketches in Anatomy For The Artist written by Jenó Barcsay – a professor at the Budapest Academy of Fine Arts. Nhu Thị added a lantern in the right corner of the 100cm X 100cm painting to cast a yellow hue across the five calves huddle on the ragged floor and balance the proportions of the two and a half men pushed to the left side. The way they huddle like women for hire on a bad business night underneath the thick shadow that dominates a third of the painting activates one’s imagination about male prostitutes. Nhu Thị worked on this painting without emotion; neither obssesed by sex nor having had related experiences.

He had visited once before with an acquaintance, a lone bird separated from the flock of literatis, before returning to her hermitage alone. Slightly bald, with firm arms and thighs that belied his old age, he’d been successful in both political and romantic pursites thanks to life-or-death tussles, literally and figuratively. Because of these aforementioned qualities, he considered himself ripe enough to fall without waiting to be harvested. Đĩ Đực had stifled him with a domino effect of tangled assumptions, which finally led him to conclude that the artist’s sexual desire is so excessive that to quench her thirst, she had to use brush and color to caress every muscle fiber of the five inanimate thighs on the canvas. He would thus martyr himself to save Thị. Before ‘letting the goat eat the grasses,’ he declared, with certainty: there’s a story behind each painting.

What is behind each story?

As a university student Nhu Thị stayed several years in a women’s dormitory overseen by nuns from the Saint Paul catholic missionary order. Over forty girls from many regions flocked to city D. to study in the university’s different departments. Their parents sent them to secluded catholic dormitories for no other reason than safety, moral safety at least. Each person was muffled into a tiny personal area that resembled an industrial chicken coop compartmented into standing shelves; the front of one shelf served as the back of the adjacent shelf; the wide-open cage door connected to the hallway bustling with girls of “golden branches and jeweled leaves” from decent families.

Unlike the other cages positioned between two shelves, Nhu Thị’s sleeping space stood at the end of a row with a brick wall on the left that separated the nun’s room from the chicken coop. Behind the shelves on the right was a nook belonging to a medical student Từ Vi. Every night after the lights were turned off, Từ Vi furtively climbed into Nhu Thị’s private 80cm x 180cm bed and complained about the cold.

Vi had long, thick hair and vellus hair growing all over her body as if she suffered from Cushing’s syndrome of the adrenal gland. Seen at a tilted angle in the sunlight, the silky strands glowed on her face. Her wet, wide eyes contained a straight and challenging glint. Her slender chin jutted forward prominently like Jodie Foster’s. She had thin lips, that, whenever she smiled, revealed upper teeth that were worn down from being ground in her sleep. Every one of these things attracted Nhu Thị. In contrast, Vi liked to gaze at her female friend’s bone structure. A round skull holding twisted thoughts regarding every matter; full lip muscles, their movements at odds with every word she uttered; delicate and translucent nasal ala revealing the blood vessels that ran a sinuous path before being cut off at the cartilage wall.

The cold of a winter away from home is different from the winter’s cold itself. They wrapped their arms around each other’s shoulders, necks and waists, strolling around the school yard after dinner. Together they inhaled and exhaled during hot bowls of bún and chili, trembled while bathing with water scooped from a well under moonlight, their minds wandering on clouds and rivers. They snuggled into each other, and it didn’t stop there. Thị panicked the first time her body quivered, unsure where Vi learned skills that seemed both natural and adept; Thị slowly let the kinesthetic stimuli open her other senses’ circuits. While all doors, small and large, to their bodies were wide open, they tried to keep the noises low, even if on one side was a brick wall and the other an empty bed.

Every year, in June and July the dormitory was desolate and quiet. University students had summer break, and most of their parents took them home, except for those who needed to stay to study for exams. For different reasons, Nhu Thị and Từ Vi remained amongst them. They drenched and enraptured in every corner of the empty house. They sometimes stared at each other to examine themselves rather than to observe the person in front of them. Eventually, enough signs allowed the nuns, who were sensitive and had personal experiences, to recognize the low voices in the choir. They responded with lengthy moral lessons and strict punishments that made Vi and Thị consider their relationship was no longer safe.

For solace and safety, Thị decided to leave the dormitory and rent an outside room. The new place was in the back of a three-compartment house that had been refurbished and fully-furnished with chairs, tables, shelf and a bed; it was enough for a single person and the landlord kept lenient rules. Rent was lower than the monthly payments made to the nuns because the tenants had to take care of their own food and laundry. This helped Thị explain the move to her family. Oddly, in this secluded corner, which was cared for as an ideal nest, Thị suddenly didn’t enjoy meeting Vi anymore. Thị’s strange attitude devastated Vi.

How to explain? Did the need for secrecy in the dormitory’s communal setting serve as a catalyst for desire? Did Từ Vi’s sporadic yet constant attempts at seduction hurt Thị’s chronic yet irregular arrogance? Is moral merit assessed and labeled in accordance to each decade? Culture seasoned by geography? Can external influences contort the shape of a relationship stored in a round skull? Deep down, did Thị still consider marriage an upstanding constraint and motherhood an innate desire?

Before there could be any conclusion to the situation, political and social upheaval forced them to lose each other for many years. After graduating from medical school, Vi now half-heartedly serves in a ward-level health unit. Thị abandoned art for petty advertising work. Sometimes relying on the residual knowledge gained during the years studying art, Thị occasionally doodles for pleasure. After the shattering, each aimlessly occupied in their personal lives. One divorced her husband, the other is a single mother. This is the story behind Đĩ Ngựa. Yet while smearing the oil paint across the canvas Thị had no idea why she was painting it until her whole body trembled, grew soaked as if she’d been thawed. Each window was opened. On one side, Từ Vi’s wet eyes hidden under the chestnut mane, Nhu Thị’s hair interwoven with its tail. They appear trapped in a spiked forest.

Đĩ Ngựa was never hung up; no appreciator given the opportunity to deviate the artist towards sexuality. No suggestive text messages.

Written by Trần Thị NgH. NgK, 03.2016. Translated by Paul Christiansen and Nguyen Thi.

–

Translators’ notes:

1. Nhu Thị: Thị is a word that signifies female; its uses vary. It can be added in front of a name to refer to lower-class women in Nom traditions. On its own, Thị can be used to refer to women in the third-person with a derogatory tone. In older Sinocentric traditions, Thị comes after a family name. Modern-day usage of Thị often employs the word as a middle name to signify that the person is female; Thị used as a first name is almost nonexistent.

2. Letting the goat eat the grasses: thả dê ăn cỏ in Vietnamese, originally a Chinese idiom (放羊吃草 or 放牛吃草) that means to let loose, to set one free.

3. Độc Cô Cầu Bại: Dugu Qiubai in English, an invincible swordsman in Louis Cha’s wuxia novels, his name can be translated to “a loner who asks to be defeated.”

4. Golden branches and jeweled leaves: lá ngọc cành vàng in Vietnamese, refers to pretty girls from wealthy households.

Originally published in Saigoneer.

Author Bio

Trần Thị NgH was born and grew up in the South of Vietnam. At 15 she started writing for teenage columns in some newspapers then became a regular writer of many literary magazines in Saigon until the Vietnam War was ended with the North as the winning side.

Trần Thị NgH was born and grew up in the South of Vietnam. At 15 she started writing for teenage columns in some newspapers then became a regular writer of many literary magazines in Saigon until the Vietnam War was ended with the North as the winning side.

Her first collection of short stories, Những Ngày Rất Thong Thả (Wandering days), was published in 1975 by Trí Đăng press, Saigon, Vietnam but not distributed due to the fall of Saigon. Since then she has published three collections of short stories in Vietnamese outside of Vietnam that were later published in Vietnam: Nhà Có Cửa Khóa Trái (Locked in; Văn Nghệ, California, USA, 1999; Hội Nhà Văn publishing house, Vietnam, 2012); Lạc Đạn (Stray bullets; (Thời Mới, Toronto, Canada, 2000; Văn Học, Vietnam, 2012); and Nhăn Rúm (Screwedup; 2012, La Frémillerie, Paris, France; 2012, Hội Nhà Văn, Vietnam). Her latest novel Ác Tính (Malignant) reached her readers in 2019. She lives in Saigon and Paris.

Paul Christiansen received his BA at St. Olaf College and his MFA at Florida International University. His poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in Atlanta Review, Best New Poets, Pleiades, Quarter After Eight, Threepenny Review, Zone Three and elsewhere. A former Fulbright Fellow and winner of two Academy of American Poetry awards, he currently resides in Saigon and works as content director for Saigoneer.

Thi Nguyen writes and researches about cultural history, technology and gender in Asia and Vietnam.