At the site where the wound will occur, we know that she was in the garden, the one she had cultivated, seed by seed, shortly after moving in with her husband and their eleven children, all of them together again after years of separation, her husband’s and sons’ feet in America, her daughters’ and hers in Vietnam, first in Saigon then a place unmentioned by the coast, underground, in hiding, waiting to make a successful bribe so they might board a vessel, any vessel: collective bride in dark waters facing an unknown stage. Bướm bướm, she whispered to my mother, butterfly, the word my mother used to reference our genitals, two cupped wings like a heartbeat, bướm bướm. In hiding all that year unmentioned by the coast, my mother as a young girl had her first period, its dark liquid unseen in their nest underground. Bướm bướm, the smear of red between my thighs perfectly symmetrical. Two lips pressed together as if to kiss, or to strike.

*

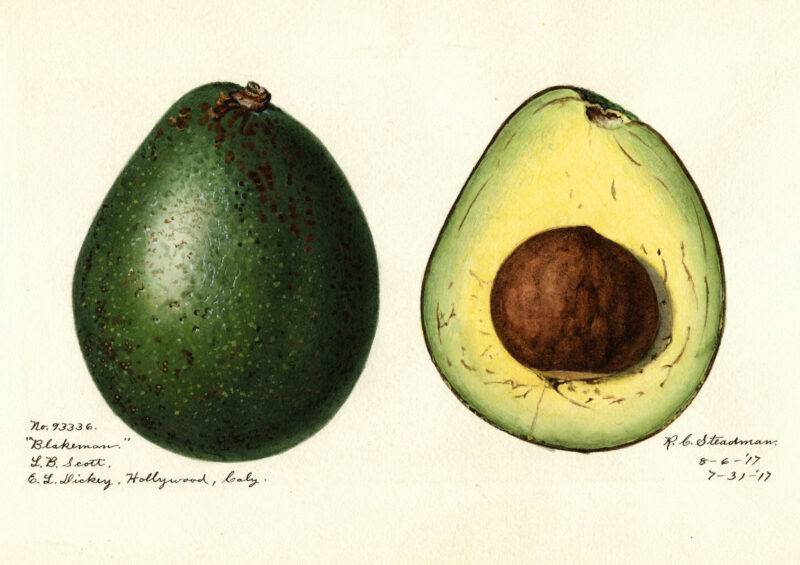

At the site where the wound will occur, there will be two tiny holes, the size of motes. When a spider bites, she thrusts fangs into her prey, fangs curved in order to hold the prey in place. In the case of megafauna such as Bà Ngoại, a black widow strikes because she is startled. Through the chin-height window above the kitchen sink I see her moving through the thick foliage of her compact garden, one hand directing water from a hose, the other moving in tandem to words I cannot hear but know from the movement of her lips. It is almost time for the avocados, she will tell me, and do I remember where this tree came from? When my mother met my father on a Californian campus in 1983, they stood under a tree which bore fruit foreign to both. My mother brought one home cupped in the palm of her hand, and her mother planted the seed. Together the women shared its flesh. Together the women shared flesh.

*

Sometimes the skin’s surface needs to break or be cut in order for healing to begin. The majority of antivenins are administered intravenously, that is, they take place within or inside a vein. Fang into flesh, needle through then under the skin. In a lab someone will seek to understand the biomechanics of spider fangs so as to inspire new medical devices. Into her body, my father’s mother administers insulin. When examined up close, our pores make up a canvas for needlepoint. Health questionnaires do not ask if there is a history of violence in your family. To the question not asked, I want to ask how many generations should I go back? When I dress exactly as my mother did on her honeymoon is it not mimicry? One creature evolving to resemble another, in advantageous antipredator adaptation. But what if your predator also looks like you?

*

A foundation myth holds that Âu Cơ, the princess of the mountain, married a prince of the sea, Lạc Long Quân, and later gave birth to early kings of the Vietnamese people. There are no mentions of daughters; if they existed, we know not what they did or what happened to them. The ancient Vietnamese did not have a stable family system as men and women lived together at will, a tendency antithetical to China’s success in establishing rule in the region. Eventually, patriarchal wedding rites found their way into the home, a site where early in the morning, ông ngoại brought gifts of dowry to bà ngoại’s family, marking what later became the third of six ceremonies in what was likely a well-suited (read: arranged) coupling. As a child, bà ngoại took pride in overseeing the field workers of her family estate. Ông ngoại was a well-read man who must’ve been familiar with Marx, though it is unclear if he discussed such topics with his wife. I know she was responsible for going to the market, later taking my mother along with her. How tender a mother’s hand at the small of her daughter’s back.

*

Thirty-two years after they kneel before the altar bowing at pictures of the bride’s long-dead ancestors, the slender sticks of incense burning in their hands as they bow to their parents, grateful to have been protected up until now and bow finally to each other as bride and groom, ash gathering on their knees, they find themselves in a hotel room in Saigon, where their daughter wakes up to the sounds of her mother’s nightmare. Whether it was a ghost of war or the ghost in the family, I did not know. As I blinked in the well of darkness which seemed to hold us hostage, I thought I saw my brother’s back, the ridges of his spine refracting moonlight. This family has no son. On an evening folk music cruise in Huế, we watched four dancers sing and play the gourd lute. One of them seemed to find me as she went through the routine. My gaze followed her in return. She reminded me of me when I was her age. When I was a young, I wanted to be just like her.

*

Squatting in the kitchen of her parents’ home, my mother finds herself in Saigon as she found every day of her life. Had she not fled with her mother and sisters, they would be here still, like long beans gathered in the same plastic basket, each with their own imperfections. There is a point at which the body, no matter where it grows, grows no differently than in any other place. Rinsing herbs, the body makes the same movements, takes the same steps. As soon as she leaves this home, she is already on her way back to it, though the journey might take longer than she could have imagined. Upon returning, she no longer recognizes the place, nor her reflection in the mirror. Mother, con nói chuyện với mẹ from here, a place where only words có thể đi được. Each time I look into the mirror, I see you with your back turned toward me.

Author Bio

A poet and multimedia artist, Diana Khoi Nguyen is the author of Ghost Of (Omnidawn 2018), which was selected by Terrance Hayes. In addition to winning the 92Y “Discovery” / Boston Review Poetry Contest, 2019 Kate Tufts Discovery Award, and Colorado Book Award, she was also a finalist for the National Book Award and L.A. Times Book Prize. A Kundiman fellow, she currently teaches in the Randolph College Low-Residency MFA and will be an Assistant Professor at the University of Pittsburgh this fall. dianakhoinguyen.com

A poet and multimedia artist, Diana Khoi Nguyen is the author of Ghost Of (Omnidawn 2018), which was selected by Terrance Hayes. In addition to winning the 92Y “Discovery” / Boston Review Poetry Contest, 2019 Kate Tufts Discovery Award, and Colorado Book Award, she was also a finalist for the National Book Award and L.A. Times Book Prize. A Kundiman fellow, she currently teaches in the Randolph College Low-Residency MFA and will be an Assistant Professor at the University of Pittsburgh this fall. dianakhoinguyen.com