Diana Khoi Nguyen’s debut collection Ghost Of was a 2018 National Book Award finalist. Her poem “Đổi Mới” was recently featured in our OUT OF THE MARGINS series. Here she talks with Vi Khi Nao about Ghost Of, a collaboration in grief, getting lost in bucket lists, and empathy.

VI KHI NAO: Do you agree with Terrance Hayes’ description of your work as “dream memoir”? What do you think a dream memoir is?

DIANA KHOI NGUYEN: I welcome the particular subjectivities of those who encounter the work, and in Hayes’ case, yes, there very much is a dream logic at work throughout: key events and memories emerge, but not necessarily exactly as they occurred at the time. Impossible things occur, or are expressed, sometimes terrifying things, sometimes deeply longed for things. I’d define a ‘dream memoir’ as autobiographical work where memory and recollection intersect with dream logic.

VKN: On Triptychs: during Vietnamese functions we are often told/reminded by Vietnamese adults to never take a picture in a group of three – it implies bad luck. Your book, Ghost Of, is divided into three parts with photographs included – which leads me to believe that a book can be a photograph too. Do you think there are ways we as artists can subvert a “hex” or a “jinx” into something that brings good luck? I have always loved the number 13. I often associate it with luck and fortune. Do you see “providence” or “fortune” in your triptych?

DKN: Oh! I love this idea of a book as a photograph: a capture of a moment (in long exposure)—in particular, I’m reminded by your words of Mary-Kim Arnold’s essay collection, Litany for the Long Moment, a book which also serves as a photograph, a kind of long(ing), looking. To be frank, I recall always being aggressively hostile to the various “bad luck” things my parents and relatives would warn me against. Which is to say: I would do more of the “bad luck” thing to prove the absurdity of the belief. Yes, I think artists can subvert this belief in “bad luck” because what is the origin of a “hex,” “jinx,” or “spell” but language? We are spinning language—and we create new realities.

Ghost Of carries three sections because there were three siblings; I wanted the book to be a trinity of the siblings, which is also a way of remembering the one who is no longer living.

VKN: What is the best way to subvert these inculcated beliefs in our Vietnamese culture which seem so prevalent? If there are three siblings in your work, which sibling is you? Which section is your brother? And, can you talk about the current length of your hair? Is it short? Is it long? When would you like to be bald?

DKN: I’m not sure about the “best” way, but I found the following effective: to do the bad luck thing in secret, and then later tell my mother about it (especially if the supposed bad luck thing turned out to be a kind of “good luck”). Of course, my mother would find other reasons for why the bad luck didn’t “work” or she’d chide me and warn me against “pushing my luck.” For someone (my mother) who highly subscribed to fate, she also put a lot of weight into free will by way of superstition and luck.

I am each sibling, and each sibling is me and the other—interchangeable, but also separate, alone unto ourselves. There’s a fluidity in how I remember us—mistaking a moment that I experienced when home videos late reveal that it was my brother, or my sister, and vice versa.

Oh my hair! I was just thinking how it takes an interminably long amount of time to grow it back out, and by the time it is “long” I am so sick of it that I cut it all off—so I’m never satisfied. Perhaps dissatisfaction keeps me growing. My hair is both long (compared to what life outside of quarantine might recall), but also short (since I’m impatient and want long hair already). Every third week or so, I think about being bald before remembering that the return to unbaldness will be infuriating (for me as I hate parcels of hair in my eyes/my face!)

VKN: Being such an avid culinary artist yourself, what ideal course would you make for your brother? 5 or 10 meal courses? Is there a favorite number your brother is drawn to? Though your brother has the right impulse – I don’t think I would want a fancy French cuisine for my last meal.

DKN: I don’t mind a high calorie last meal for Oliver—I don’t have any preference, really; more curiosity for his choice(s), his decision. He was a very picky eater, so the ideal course I’d make for him might seem odd for a meal, but not for a last supper (considering photographs I’ve seen of death-row inmates’ last meals). I think I’d recreate the following for him (if he were alive): glazed yeasted donuts, recreation of a burger (cross between In-N-Out and Shake Shack), bún thịt nướng, and more donuts. What I’ve been offering to his Buddhist altar (in an attempt to nourish him as a deceased being) have been small portions of my various meals: an attempt to keep him present, in mind, though he likely would reject most of what I make and eat (Oliver was not an adventurous eater). I’m not sure if he had a favorite number, but he had a favorite cat; I’m sad not to be able to recall the breed anymore. At times, I think: if he had been able to have a pet, perhaps he might still be alive?

VKN: Donuts are an awesome idea! Eating different kinds of inflated circles of life seems like a good gesture to discontinue a life. Would your brother like bún bò Huế? I just think it’s such a good dish to die on. It’s so fatty and red and its broth is so robust and I don’t know why I associate lemongrass with death. What herb or spice do you think resembles the afterlife the most?

DKN: No, he would hate it. He doesn’t eat much meat and he would definitely not appreciate the blood cube! I love the idea of associating lemongrass with death. It certainly feels like an instrument to me. A wand? A weapon?

Diana reads “Triptych” as part of the Ours Poetica series on YouTube.

VKN: Since home videos are harder to cut out (much easier to erase) than photographs, what method would your brother, if he were able to revisit those videos, use to blur or cut out his presence? Do you think he is an artist/performer/poet who is secretly creating collaborative work with you? An artist who hasn’t been institutionalized, validated by informal or formal academic structures? That your Ghost Of is a collaboration with him? That his suicide is an elliptical gesture, imploring you to continue the dialogue or monologue of his being? I love how the word “being” phonetically resembles “beeing,” the thing that provoked his insomnia. Do you have insomnia? If so, do you experience it frequently? What do you use to cope? The reason I ask if he was a performer is because of how cautiously and meticulously he removed himself from each photograph, cutting himself out so precisely—there was utter reverence and as well as irreverence in his nocturnal act of erasure that shares mutual identity with someone who values life and art and perhaps discipline very deeply.

DKN: Ghost Of is absolutely a collaboration with Oliver—it documents one part of the dialogue in my attempt to reach him, and others in my family. I’ve been carving into the home videos via an accidental discovery / loophole in my film editing software: through use of found green and blue screens. Wherever there was green or blue (sky, grass, a dress), I could overlay other images, other videos—and the green or blue would be replaced, “cut out” if you will. But also filled in. Layered, contained. To be honest, I think my brother would have destroyed the videos if they had been within his field of vision—I’m not sure he would have taken time to cut portions of the reel where his image occurred (analog)—and he certainly wouldn’t have taken time to do so digitally. Oh yes, but not a performer per se—Oliver was meticulous in everything he did: playing the piano, basketball, cleaning his teeth, teaching himself to drive stick shift—it wasn’t so much perfection as a sense of the right order and form for things. There was a grace and beauty to all that he did and touched. Except he was always dissatisfied, finding flaws. As I type this, I recognize myself in him, him in me. If he was going to do something, he was going to do it in the way he found to be the ‘best.’

No, Oliver’s suicide is not an elliptical gesture; he wanted to cease being alive, and he made it happen. If he had survived the attempt, I think he would forbid me to engage with him or any part of his life. In many ways, I am able to violate his wishes because he does not have physical agency to request me not to. And I don’t think of my engagement as a kind of violation—but a revisiting, recounting, documentation of my experience as it intersects with his and others.

Oh the deceased “beeing”! I don’t have insomnia, rather the opposite: I can sleep anywhere, any time—easily. But during my writing periods, I do stay up very late—sometimes until just before dawn.

VKN: You write on page 45, “That which is the identical on land is fraternal underwear.” With regards to insomnia, life, and death, are you land or are you water?

DKN: I am always on land and in the water—the hardest part about being in quarantine (for me), is my inability to swim (also, I live in Denver, CO where there are not many natural bodies of water for me to frequent). Even now I am devising ways to be in water (am thinking humorously of Daryl Hannah in Splash). Life, death, sleeplessness is also a kind of fluid state—but water involves land (the ocean floor is a kind of terrain, a landing, if we can reach it).

VKN: After writing the book—a gesture of therapeutic liberation—how was your relationship to the book tour, the constant reading in the public sphere that forces you to relive the trauma over and over again? Was it like the woman who has the ability to live multiple lives as in the TV series OA, forced to down and die over and over again? Can book tours jade the heart? Or can it be an invigorating experience for those who deal with trauma on a daily basis?

DKN: There was no planned book tour—just two intentional gatherings of family and friends to be in community (and safety) to usher the book into the public sphere. I worked very hard with my therapist on how to maintain safety (and boundaries) for myself while in public spaces which request performance. For over a year, I would only accept invitations to read if there was at least one familiar face who kept me grounded or made me feel safe. I couldn’t read the work to a room of strangers. For me, readings were exhausting, but what gave me a kind of solace was to witness the grief of strangers, to hear their stories of loss, to be present with them when they shared with me. There were a lot of quiet moments touching hands with strangers at the book signing table. I felt seen in those moments, and I tried to see every one of them.

VKN: Such experiences of touching, of quietude, of sorrow, of silence—do you feel the birth of Ghost Of has turned you to a mortician of some kind? One who helps others translate fluidly from one language of sadness or bereavement to the next? Do you feel that life in relationship to poetry is about learning how to transfer one bucket of sadness into another bucket of sorrow? And in that translation of water, life finds its force in the act of being poured?

DKN: Yes, many overlapping experiences of grief, silence, and physical space-sharing. I’m not trained for much—so no, I don’t feel much like a mortician, but as a fellow bystander / remnant in the wake of the absence of others. I think survival is learning how to be with all the buckets but to also welcome unknown buckets—and to somehow have hope amidst tragedy. To celebrate the quotidian, the mundane, the moments unmarred by sadness. But to also honor the sadness by allowing it into a full register of feeling.

VKN: If you were given an opportunity to collaborate with Michael Phelps, what poetic project do you foresee manifesting from your body and his body? How strong of a swimmer are you? Have you ever come close to drowning? In one of my favorite stories from Miranda July’s first short story collection, there is a scene in which one of her protagonists is teaching senior citizens how to swim without a swimming pool. They have just their faces dipped in a trough while they practice their butterfly moves or learn how to take deep breaths with their senescent faces dipped in water. Would you swim that way too?

DKN: I’m a very strong swimmer (I can swim long distances in the ocean, in fresh water without fatigue), but I’m no Michael Phelps. You know, I don’t know what I would do with Phelps—since it would also depend on the conversations I’d have with him, and what I’d learn about his imagination and his tendencies for making. Perhaps I would ask him how one can create the illusion or sensation of swimming if one is landlocked without access to bodies of water. I once saw a mattress ad with him diving into it—perhaps dry swimming collaboration. Oh, I love that you shared that part of a Miranda July story (which I haven’t read, but I love her video work)—yes, something like swimming without a pool. What are other forms of swimming can we place our bodies into motion toward?

VKN: What is your favorite video work of hers? I love how tender and cheerfully perverse and vulnerable her work is, both video and writing. How does one measure how fast one’s body travels in a dry swimming competition?

DKN: I LOVE Me and You and Everyone We Know! Yes, I’m drawn to the vulnerability, too—and the playfulness without being self-conscious. I’m sure my husband could devise a sound method to measure dry swim body displacement—given the right instruments.

VKN: I think people who do commit suicide are often not appreciated deeply for how much they value and appreciate life—sometimes more than those who choose to continue to exist. Do you think eels are very inky? If an eel were to ask a bee out on a date, what would it do to seduce the bee into saying yes?

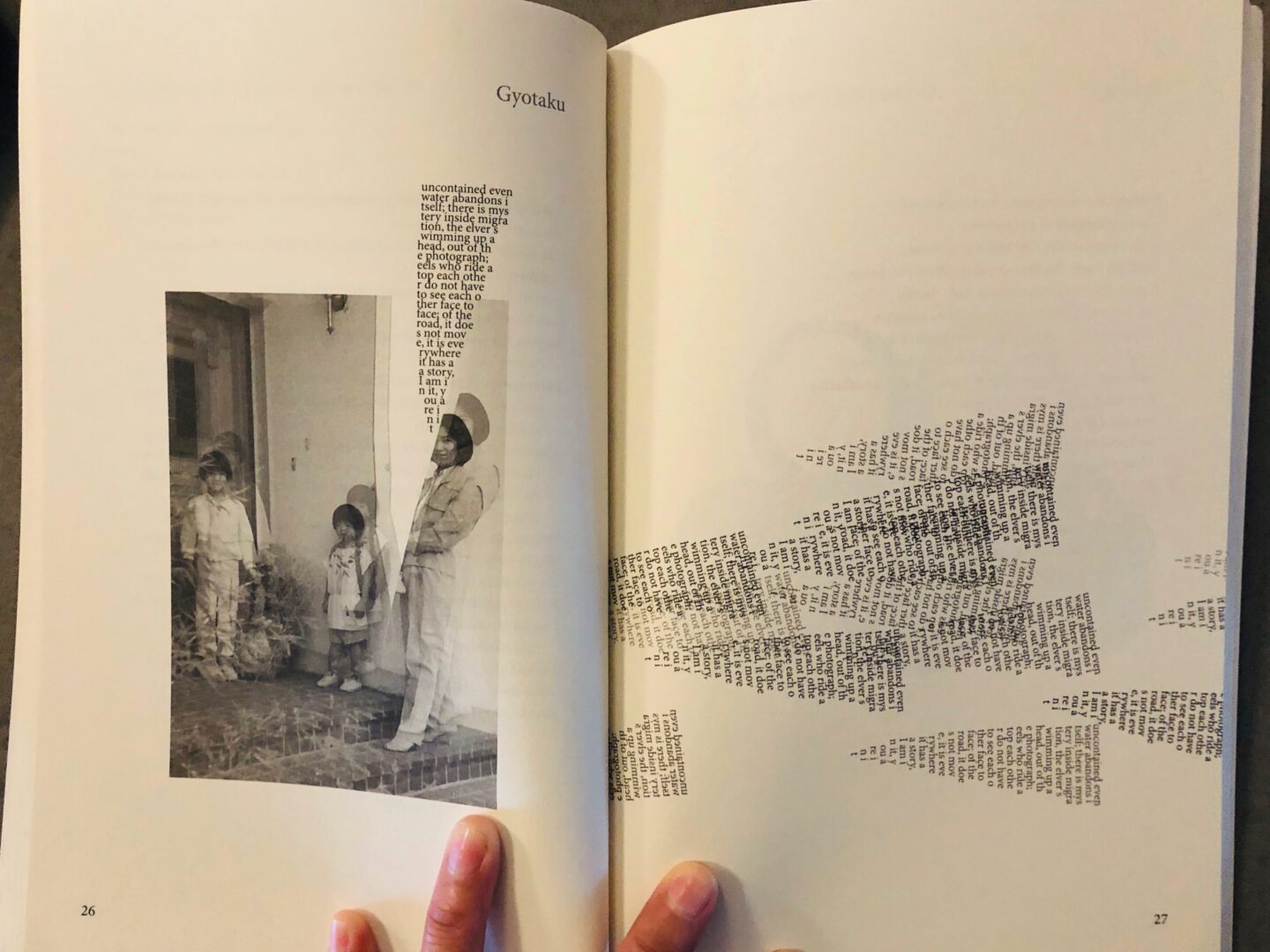

DKN: Yes, perhaps there is truth in that—that those who commit suicide perhaps think much more carefully and attentively about being alive. Perhaps I speak only for myself when I say that by continuing my life (alive), I have very often taken for granted my life and not questioned it as when I was suicidal (in teens and 20s). Eels are my ink, the dead body is a letter, a form to put on the white page.

Hmm. If the eel could cover itself in honey and writhe around in bright flowers, perhaps that gesture could lure a bee to stay, to linger, for a little while. The asking of the eel would then become the date itself.

VKN: Can you talk about your suicidal tendencies in that part of your life? What was happening in your life that compelled you to travel down such dark paths?

DKN: I don’t wish to go into much detail here, but I’ll summarize it in this way: my siblings and I suffered multiple forms of abuse from our parents, in addition to intense oppression (no forms of film, TV—even reading books for pleasure was forbidden; I didn’t go to a birthday party or other social gathering until I escaped to college). During my teens, I knew I had two options: kill myself and end my suffering, or to work stealthily toward legal freedom; I chose the latter, and left the house on my 18th birthday—because there was so much I wanted to experience before I died (and I still feel this way). It’s taken many years and the death of my brother for me to have a working relationship with my parents. They’ve grown as I’ve grown, and all of us are getting older.

VKN: What is on your bucket list, Diana? What would you like to achieve before you die? I do feel that the reverse of suicide is filling in the gaps left by your brother.

DKN: More travel. Papua New Guinea and well, other places I know not very much about. To spend a lot of time underwater (my husband and I were planning on getting started on SCUBA certification, but now we’re sheltering in place). I definitely would like to swim in every major body of water (without fear of danger). My life post-Oliver’s death is very much about actively pursuing all my dreams (something I was shy about previously). The funny thing is: Oliver hated traveling—but when I swim, I imagine he is with me (his ashes were scattered in the Pacific Ocean).

VKN: Why did your brother hate traveling? A lot of his natural impulses seem a bit anti-life (picky about food, not liking traveling, cutting photographs of himself out).

DKN: I think Oliver hated disruptions to his routine. Like my mother (who also hates traveling, including a trip back to Vietnam), Oliver prefers his bathroom, his sink, his old bed, his desk, and so forth. Familiarity was key to his comfort.

VKN: In another interview you wrote, “I then went to Hawaii and I recreated the honeymoon scenes, but with me. It’s a retracing of her steps, in part maybe to further empathize with her, to understand her, because in many ways I don’t understand her.” If you were able to visualize what understanding your mother would look like—what would that visualization be? If visualization is hard, if there is a film or a book or a national park or an ideal travel destination that would resemble that understanding—what would that be?

DKN: The only way to understand her would be to be her, but also be everyone around her (her ten siblings, parents, my father, and so forth)—I can only approach understanding as an asymptote (except I don’t get very close). The closest I’ve gotten is hearing other 2nd generation Vietnamese Americans recount stories of their parents’ odd behaviors and idiosyncrasies; in these stories I recognize my mother and begin to have a larger diasporic context for her behavior and actions.

VKN: Do you feel when you create work intensely over a course of 15 or 30 days that your consciousness has to do the emotional, intellectual, literary legwork ahead by reading, watching films, engaging intensely with food and life and travel, in order to have a decent well of ontological materials to make new work? Or do you think an artist/poet/performer can produce work in isolation? What is an ideal influence?

DKN: I think both can occur—and the product of either would be different of course, save the signature characteristics of the maker. I love turning myself into an ultra-absorbent sponge-pot into which I throw varied materials—and then see what comes out. A bit like making a spell! My ideal (perhaps unattainable) influence would be to have literacy and cognitive ability to grok all areas of study (sciences, technology, humanities, etc.)—I wish I had enough time to know more—and thus welcome more material, data into my sponge-pot. Instead, I’m limited to what I can obtain (which is a product of privilege) and what I can comprehend in a timely fashion.

VKN: Can you talk a little about your marriage? What is your husband like? Can you talk about your courtship? Is it similar to buying noodle soup? With all the side glances?

DKN: Sure—I’ll start by saying I never wanted to be married, or thought I would get married (which is somewhat similar to my aggressive hostility toward cultural or familial superstition). I didn’t have much faith in the institution of marriage, and certainly had no positive examples for it for most of my life. In summary, my husband is like my father: kind, 5’10”, curious about the world, an engineer (in mind and occupation), but also fosters a generous imagination and capacity for collaboration and making. We met on Tinder, and I like to report that I reluctantly had to accept my serious feelings for him. Our courtship: lots of cooking, exploration of the outdoors, time spent with 3-4 dogs. When we go somewhere new for us, domestic or international, we like to get lost on purpose (sometimes together, sometimes apart)—I love our joint independence and coming together and treasure it a great deal.

VKN: What is your definition of empathy? If you were to define it solely in words alone and not as an infant of a multimedia object? In one of your interviews, you wrote, “I think I was afraid of mining my family trauma for the sake of art-making.” Can you talk more about this fear?

DKN: For me, it’s a being beside, a being with, but with proximity so close you could at times enter into the perspective of the other. It’s a close kind of witnessing.

My materials are documents which feature members of my family—I don’t have sole claim to the material, and yet I work with it, manipulate the footage, the memories for my own purposes. I want mostly to mine my past, but in so doing, my family gets included along the way. How I come to peace with this: my intent in my projects, and how I offer these projects to any public sphere (if so).

VKN: The drawing you did of a bear when you were six…that bear looked like a light brown star that went through the washer. Have you thought about writing a children’s book? I have a strong feeling you would excel in that form. Also, as an addendum to that book you wrote and illustrated when you were six: does your note about your precocious ability to untangle “necklaces, thread, yarn” also translate to the ability to undo “emotional, intellectual, psychological entanglements?” If so, what concept in this universe is a hairy ball of fur or thread for you? How would you go about untangling it?

DKN: I love this strong feeling of yours!! It has always been a dream of mine to write children’s books. But I think I can’t pursue this until I’ve read a lot of them and also perhaps have a child. Maybe one day. I have wanted to write an adaptation of Tarantino’s Kill Bill but underwater, rhymed—it’d be called Krill Bill or something like that. In a way, it’d probably be more for adult reading than for the child, but I don’t really have access to how a child’s imagination works anymore—so I wouldn’t know.

Hmm, I can’t speak to my ability to untangle more abstract forces in our life, but I do work knots (of abstract and concrete nature) over and over in my mind—it’s a visceral, futile-feeling thing, as if trying to untie something in my mouth using only my tongue. My attempt to untangle and access what part of the universe I can is really to figure out how to capture various forms of experience via visual forms (and text is also a visual form).

VKN: What is the most difficult thing about learning Vietnamese? Do you love its tonality? Its diacriticism? One of my favorite words in Vietnamese is “Người ơi”—“Oh, people!”—but in Vietnamese it seems like a way of talking to everyone and no one at once. Do you have a favorite Vietnamese phrase or word—one which you find yourself returning to for either comfort, inspiration, or boredom?

DKN: I do love its tonality, but find literacy so difficult! It’s hard for me to sequester my knowledge of a Roman alphabet and adopt the signified sounds of the Vietnamese alphabet—the Roman alphabet seems to get in my way. At times, I am quite hungry for a more intimate knowledge of Vietnamese. One phrase (and I have no idea why) that recurs in my dreams, in boredom, unbidden—is such a mundane one, but I think I must be drawn to its cadence and repetition: “Bây giờ là mấy giờ,” or, ‘What time is it’—except how I literally translate it is: right now is what time? But in looking at the actual words, perhaps more like: “this time is what time?”

VKN: I love how romantically redundant Vietnamese language is. To say the word apple for instance “trái táo”—like place a Mr. or Ms. or Professor in front of its name. In in that phrase, “Bây giờ” —the “giờ” is repeated, not for emphasis, but for poetic texture. I think Vietnamese is incredibly poetic! Not only poetic, but also very informally formal; there is a chivalrous, old-fashioned draw not only to how people address each other, but also how inanimate objects address each other in time. In writing and literature, brevity and economy of language and pithiness are often condoned or celebrated, but in Vietnamese I feel that poetic texture is at the heart of economy/economic expression. There is concealed humor traversing beneath the epidermal surface of Vietnamese phrases. A meta-acknowledgement: “I know I am a sentence and this is how I could be more of a sentence in your mouth.” In that sentence that you love “Bây giờ là mấy giờ”—I think time is addressing himself: “dudette ơi, giờ ơi – mấy gời rồi.”

DKN: Yes, so wonderfully (and humorously) put—it really is! I haven’t previously thought of the repetition as poetic texture—as if to fulfill an inherent completeness of the line—which is to say: language as the art we make between, toward each other, rather than language as utilitarian communication (which would reduce “Bây giờ là mấy giờ” to “mấy giờ?”)

VKN: You are a cinephile, yes? What are your top five films and why?

DKN: Yes, I do love film! But am not as well versed as I’d like, or as my conception of what a cinephile version of myself would be, but here are my top five films (at this moment, which is to say, the top five will change depending on where I’m at): Wong Kar Wai’s In the Mood for Love and Happy Together, Rian Johnson’s Brick, Bi Gan’s Long Day’s Journey into Night, and okay—the last one is cheating, because it’s not any one particular film, but I love watching the work of Denis Villeneuve.

VKN: I love In the Mood For Love too. I love how he is able to make soup purchasing so so so sexy! Wong Kar Wai’s choice in his cinematography is just so exquisite. What is the sexiest thing you have ever seen in cinema? I also wanted to read a piece of literature or a book that captures such fluid hypnotic intoxication from mundane to aesthetical fluency. Please tell me more about Denis Villenueuve. Anything really.

DKN: Yes, I wish I could go to a noodle stall right now in a gorgeous silk printed dress! How can one be nostalgic for 1960s Hong Kong if one has never been to Hong Kong? Wai’s D.P. (Christopher Doyle) is so amazing. There’s a documentary on him I have queued up on the Criterion Channel.

The sexiest thing I’ve seen in cinema, a two-part response: (direct) the bookcase sex scene in Atonement (which was really unsexy in the filming/directing/choreography based on interviews I’ve read—and side note: I really hated that movie but loved that scene and other Joe Wright films); (indirect) the tension between Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung when they walk past each other or sit next to each other without making eye contact—Ah! So good!

Hmm, about Denis Villeneuve—there’s something about how he looks and sees—maybe angles, maybe it’s mood translated into film medium (I’m not versed in the technical aspects of filmmaking, so I can’t fully parse out what it is), but I love that scene at the end of Sicario—something about the stark representation of a shitty apartment, that curtain, how the camera moves from inside to outside—the actors (Emily Blunt and Benicio Del Toro are excellent)—but how everyday objects become activated under the direction of Villeneuve. I don’t love any of his films in particular, but I love his way of seeing. I’ll watch anything he makes.

VKN: What two filmmakers do you think should collaborate with one another? And, let me be non sequitur (though not that non sequitur): what is an impractical dish you have ever attempted? I tried once to make a spring roll with rice paper, bánh xèo, leftover pizza slices, avocado, rice and cucumber. Are you wild in the kitchen? Or do you stick to recipes?

DKN: I’d like to see David Lynch collaborate with Alejandro González Iñárritu or Krzysztof Kieślowski (deceased) with Alfonso Cuarón. Writing this reminds me of how ill-versed I am in a wide range of women filmmakers (let alone women filmmakers of color): Agnès Varda and Andrea Arnold or Jane Campion.

In the kitchen, I am not wild in an Iron Chef kind of way, and I use multiple recipes to guide my foundation for a dish, but then adapt by using what I have at hand (flexibility and accessibility are important to me). Once I did kielbasa spring rolls (with cheese), which is really just another gluten-free version of a burrito, when I think of it. I don’t experiment much with ethnic dishes as I feel like I’m still just trying to perfect each one as they are. This weekend I’ll make injera and do a little Ethiopian veggie platter. I’m staring at the bag of teff flour as I write this.

VKN: When your father asked the flight attendant, regarding the just pasta and out-of-rice situation, “Why didn’t you reap enough rice?”—if you were the flight attendant, what is the best way to respond to your father, Diana?

DKN: Oh, when this happened to the speaker’s father in that poem “I Keep Getting Things Wrong,”—I wouldn’t say that this exact thing happened to my own father per se—but if I were in that scene as the flight attendant, I think I would say to the father, “I’m sorry, the underestimation is an error we will try not to repeat in the future. Of what I have available, is there anything I can provide that might nourish?”

Contributor Bios

A poet and multimedia artist, Diana Khoi Nguyen is the author of Ghost Of (Omnidawn 2018), which was selected by Terrance Hayes. In addition to winning the 92Y “Discovery” / Boston Review Poetry Contest, 2019 Kate Tufts Discovery Award, and Colorado Book Award, she was also a finalist for the National Book Award and L.A. Times Book Prize. A Kundiman fellow, she currently teaches in the Randolph College Low-Residency MFA and will be an Assistant Professor at the University of Pittsburgh this fall. dianakhoinguyen.com

A poet and multimedia artist, Diana Khoi Nguyen is the author of Ghost Of (Omnidawn 2018), which was selected by Terrance Hayes. In addition to winning the 92Y “Discovery” / Boston Review Poetry Contest, 2019 Kate Tufts Discovery Award, and Colorado Book Award, she was also a finalist for the National Book Award and L.A. Times Book Prize. A Kundiman fellow, she currently teaches in the Randolph College Low-Residency MFA and will be an Assistant Professor at the University of Pittsburgh this fall. dianakhoinguyen.com

Vi Khi Nao is the author of Sheep Machine (Black Sun Lit, 2018), Umbilical Hospital (Press 1913, 2017), the short story collection A Brief Alphabet of Torture, which won FC2’s Ronald Sukenick Innovative Fiction Prize in 2016, the novel, Fish in Exile (Coffee House Press, 2016), and the poetry collection, The Old Philosopher, which won the Nightboat Books Prize for Poetry in 2014. Her work includes poetry, fiction, film and cross-genre collaboration. Her stories, poems, and drawings have appeared in NOON, Ploughshares, Black Warrior Review and BOMB, among others; her interviews with writers have appeared in many publications as well. She holds an MFA in fiction from Brown University, where she received the John Hawkes and Feldman Prizes in fiction and the Kim Ann Arstark Memorial Award in poetry. vikhinao.com

Vi Khi Nao is the author of Sheep Machine (Black Sun Lit, 2018), Umbilical Hospital (Press 1913, 2017), the short story collection A Brief Alphabet of Torture, which won FC2’s Ronald Sukenick Innovative Fiction Prize in 2016, the novel, Fish in Exile (Coffee House Press, 2016), and the poetry collection, The Old Philosopher, which won the Nightboat Books Prize for Poetry in 2014. Her work includes poetry, fiction, film and cross-genre collaboration. Her stories, poems, and drawings have appeared in NOON, Ploughshares, Black Warrior Review and BOMB, among others; her interviews with writers have appeared in many publications as well. She holds an MFA in fiction from Brown University, where she received the John Hawkes and Feldman Prizes in fiction and the Kim Ann Arstark Memorial Award in poetry. vikhinao.com