In this excerpt of this is for mẹ, Jess Boyd speaks to Malaka Gharib about creating art, hope and humour in the midst of the COVID pandemic.

Inspired by Ocean’s Vuong’s letter to his mother in the New York Times, this is for mẹ lives online as a borderless mailbox for Asian identified people to share stories rooted in mothers, motherhood, motherlands, mother-tongues and family.

Do you know the story behind your name and how it came to be yours?

My name, Malaka Gharib, are two words … Malaka means queen in Arabic, and Gharib means a stranger, a foreigner. Together I guess you could say it means “strange queen.” Malaka is an old fashioned name, actually, derived from my grandmother’s name, Malouk, and Gharib is the name of my grandfather. In Arabic culture, your last name is actually the first name of your father. But when my dad moved to the States, he went by the Western tradition of making his last name, Gharib, my last name. I used to hate my name and wished I had a Western one, but I love my name now, especially because it comes so directly from my family.

What is the best/worst way that someone has mispronounced your name?

Mulka Grib, Ms. Urbigkeit in fifth grade.

When you think of home/s, where do you think of?

The first thing I think of is my childhood bedroom in Southern California, which my mom has kept intact since the day I left home at age 18. I think that’s probably spent the most time daydreaming and thinking, sitting upright in my bed and listening to my CD player with my headphones, writing in my journal and reading music magazines, although I know that was all half a life away now.

How have you been fueling your creativity during COVID?

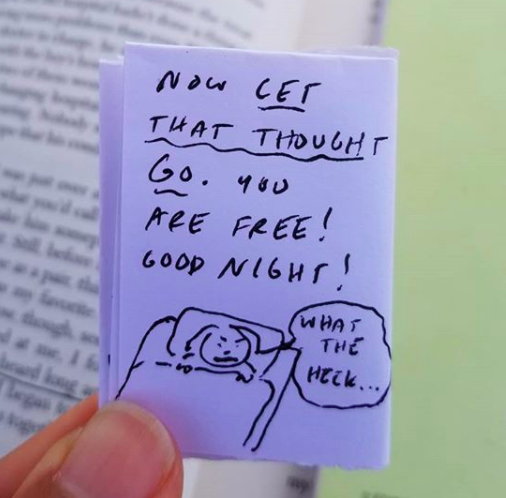

I’ve been letting myself off the hook to create, actually. Before the pandemic, I was super disciplined about drawing and writing every day for myself, with an aim to make one good thing out of that time, even if it’s just something I made in five minutes. But it’s been hard to concentrate in the pandemic. Still, inspiration is everywhere. I try to let myself be bored and empty-headed — while sitting in the bath, while walking in the park, while making dinner, laying in bed before I go to sleep. That’s usually when good ideas come. And sometimes I’ll turn it into something, or sometimes I’ll just let it go.

You have been sharing such uplifting and beautiful content around zine making during COVID. How did you find your way to zines and how did they help you navigate the world?

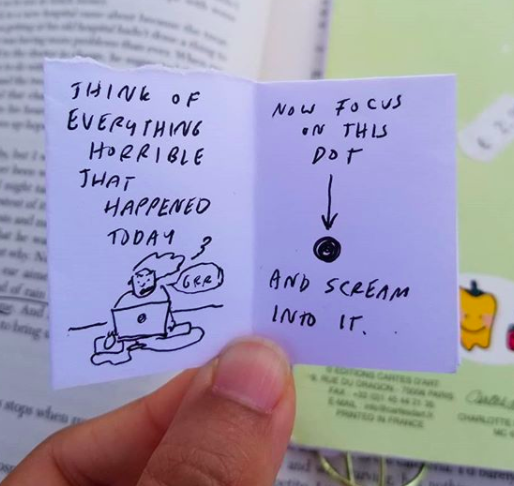

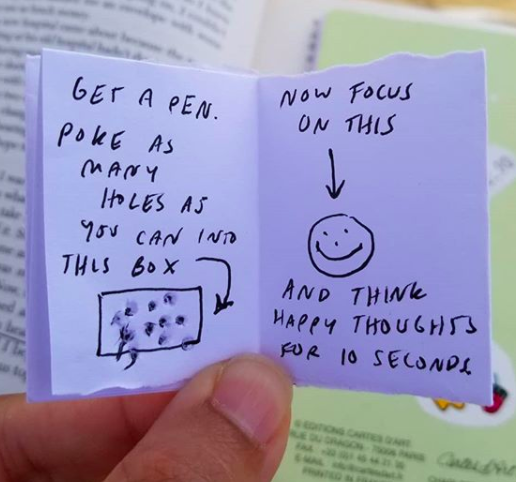

I picked up my first zine at Skylight Books in Los Angeles when I was 14. It had directions on how to make your own zine. Since then I’ve never not had a zine. In high school I made one about music (which I’ve reprinted and you can buy at malakagharib.bigcartel.com) and when I graduated college I started one about food called The Runcible Spoon. As I got older I started experimenting with the form and pushing the limits of it, and found I really liked the 8-page mini zine format. It is such a tangible manifestation of entering and exiting a world.

I like making really tiny zines and the challenge of trying to express big ideas like love, loss and heartbreak with very few words, images and pages. It feels like I am writing a haiku or a poem, or trying to work through a puzzle. How can I say what I want to say with the fewest lines? I think this exercise helped me be more intentional about word choice, image choice and the very tight and specific message I am trying to express. I keep whittling and refining everything down until it’s just the truth that shows.

How have you seen zines help create awareness and access for young people in the midst of this pandemic?

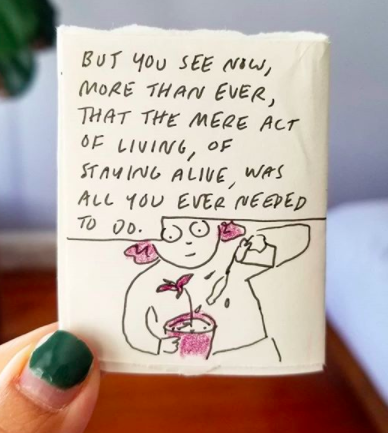

The quaranzines that people have been making in the pandemic are like mirrors — people are trying to make sense of what is happening to their lives. They want to examine their new reality, to record and not forget how they are surviving these strange times. I think what is nice about zines is that the tools to make them are accessible — you just need a pen and paper. And aesthetically they don’t need to look perfect. Stick figures are totally OK. And to finish them and see a physical manifestation of your emotions and feelings, well it feels like a huge accomplishment during a time when our lives are spiralling out of control. You can read your little zine over and over again and be reminded of how you felt in the pandemic, at a particular point in time.

Your entire graphic memoir, and so much of the art that you share on Instagram feels like a big hug. How do you go about creating artwork that can be complex and sensitive, whilst simultaneously infusing it with so much levity, hope and humour?

I only ever try to write for myself, as if I was writing in my own diary. And when you are writing in your diary you have to be self aware of your own feelings and examine them. You need to be able to make fun of yourself and to criticize yourself — and I think that often leads to thoughtful, funny and heartbreaking writing. I am also aware that my art can be too earnest so that also moves me to add more humor into my work. Otherwise it’s one huge eye roll-inducing cringefest. Yikes!

Who are your favourite POC artists and/or graphic novelists?

So many. Nguyen Nguyen of The Gulf, Deb Lee, the author of the forthcoming In Limbo, AJ Dungo of In Waves, any zine made by Carl Cervantes.

—

Artist Bio

Malaka Gharib is a writer, journalist and cartoonist. She is the author of “I Was Their American Dream: A Graphic Memoir,” about being first-generation Filipino Egyptian American.

She works on NPR’s science desk, reporting on global health and development topics such as humanitarian aid and gender and income inequality. She also writes for NPR on her experience as the child of immigrants, from talking to her Filipino mom about mental health to hosting an Eid feast for her Muslim father.

Her comics and zines have been published in NPR, Catapult, The Seventh Wave Magazine, The Nib, Saveur Magazine, It’s Nice That, The Washington City Paper, The Believer Magazine, The New York Times and The New Yorker.

Gharib is the co-founder of the D.C. Art Book Fair and The Runcible Spoon, a zine about food and fantasy. She graduated from Syracuse University with a dual major in magazine journalism and marketing.

Love your work!