When I was four years old, my uncle dropped a bowl of pho on my head.

It was the lunch rush at my family’s restaurant. I was walking from the dining room towards the door to the kitchen. At the exact same time, my uncle was walking through the door the other way and collided right into me while carrying a bowl of pho for an unlucky customer.

The tray carrying the soup slipped out of his hands when I ran into him. Before I knew it, steaming fragrant pho broth, freshly cooked rice noodles, and tiny superheated flecks of flank steak began to rain down on me like fire and brimstone. It felt like I just stuck my head into the mouth of an angry dragon.

Imagine Splash Mountain, but instead of getting a fun souvenir picture at the end of the ride, you got second degree burns covering the top half of your body.

The weird part is I don’t remember anything before the soup touched my skin — this is just what I was told later after a trip to the hospital. But as my body registered the searing pain of the pho, my consciousness ignited. It was like my brain came online at that moment and I began to register real memories for the first time ever.

I remember feeling pain. I remember being scared.

But, more than anything, I remember feeling that I really hated my family’s restaurant.

My family owned a Chinese and Vietnamese restaurant called “Da Kao” in Sioux City, Iowa — a town deep in the corn-choked guts of the Midwest. It’s a massive red-brick building with a big green sign and yellow lettering loudly announcing the name and phone number of the restaurant to a busy thoroughfare. While we weren’t the only Chinese place in the city, we were easily the biggest and most successful.

As such, I grew up as a breed of child I’m sure many of you have seen before — especially if you’ve ever been to a immigrant family-owned Chinese, Vietnamese, or even Hispanic restaurant.

They’re the kids you see just hanging out at the restaurant when you go there. They’re never eating. There’s typically more than one. And the workers at the restaurant never speak to them or even look their way like they’re ghosts in a Victorian novel.

In fact, when you see one, you might become a little unsure of yourself.

Does anyone else in this place notice the three kids sharing a tiny corner table right now? They were here when we came in like 30 minutes ago and no one’s brought them drinks or food the entire time. Am I the only one seeing them? Are they … ghosts? The lost spirits of kids who died here waiting for their order of crab rangoons to be fried?

No. They’re not ghosts. They’re Restaurant Kids. I know because I was one too.

A Restaurant Kid spends entire days in the natural habitat: Sitting at the smallest table of their family’s restaurant. There they do homework, read, draw, or, if their parents really wanted them to be quiet loved them, play on their Gameboys or laptops.

But if their parents are anything like mine and my cousins, they’re being put to work. After all, child labor laws don’t exist to immigrant families. Not when there’s food to be served, drinks to be poured, and money to be made. My first words ever were “bố” and my first sentence ever was, “Would you like white or fried rice with your order?”

Family-owned restaurants are actually a big reason a lot of Vietnamese kids learn English. You needed to learn pretty quickly if you wanted to wait tables and collect tips.

As a Restaurant Kid, you learned all the essential phrases to get by in America:

“How are you today?”

“It was great meeting you and I hope to see you again!”

“Sorry, we only carry Pepsi products.”

Restaurant Kids also got collegiate level schooling on mathematics. I learned division calculating how I’d split the tips with the waitresses. I learned multiplication when calculating tax into a customer’s check. I learned subtraction when my parents took away my earnings to “save for college.”

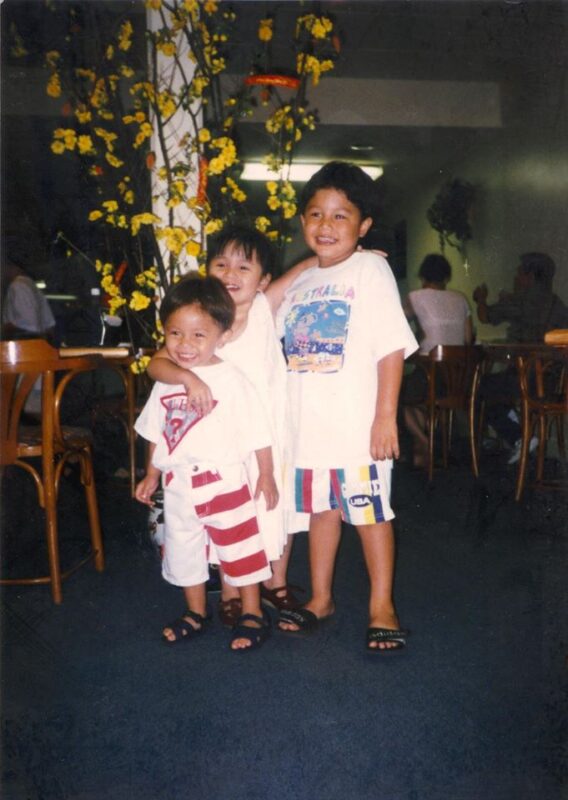

So when we weren’t in school, my brother, cousins and I spent our time at the Restaurant. While my friends spent their summers at camp or learning programs, I was at the Restaurant. The Restaurant became more than just how my family made money. It was a daycare, workplace, library, study area, nap area, and hangout spot all rolled into one.

And…I hated it.

Because for every one good memory of being a Restaurant Kid, there were a dozen not-so-good ones.

Like the sounds of your family fighting with each other in the kitchen. The shouts from your uncles as they argue over one another’s gambling problems, or for totaling another delivery car, or for getting an order wrong. The screams of your parents as the stress of raising two children while managing a restaurant in a country that’s not their own boils over like a pot of egg drop soup at rush hour.

The same noises that howl in your skull through restless nights years later.

Order up. Two number twelves and a Won Ton soup to go. Delivery for three egg rolls and a small fried rice. Remember to bring change for a hundred or you’ll have to find an ATM.

Dishes falling. Gas burning. The clang, clang, clanging of a million plates and spoons and knives and forks. The mood and the temperature heating up alongside the burners underneath the woks.

Where’s the order for table four?

What do you mean “Where’s the order? I never got a fucking order.

I put it in half an hour ago.

The fuck you did.

What did you say to me?

Long evenings after school working on my homework at my corner table, and desperately trying to ignore the shouts of my parents and uncles in the kitchen.

The Mayflower arrived at Plymouth in 1620.

I SAID THE FUCK YOU DID.

The first Thanksgiving happened in 1621 when the colonists honored their first harvests with a three day long celebration.

OH FUCK YOU. YOU THINK YOU’RE SO TOUGH NOW?

Joining the pilgrims were 90 Native Americans from a local tribe who helped them survive their first winter in the New World.

DON’T YOU FUCKING TOUCH ME. DON’T YOU DARE FUCKING TOUCH ME.

So when my mom called me to say that they finally sold the restaurant after 20 years of business, I didn’t know how to feel. It was the exact definition of bittersweet.

How are you supposed to feel, though, if the very reason that your family was able to live and succeed and thrive in this country was also the reason your family fought and didn’t speak to each other for months on end?

So I decided to make a trip back to my hometown. Though I told people I went back to visit my parents and ba ngoai, it was more to say goodbye to the Restaurant. So in 2019, a time when social distancing and quarantine were concepts as foreign as pho without lime, I flew back to Sioux City from my home in Chicago to say goodbye to the place that raised me.

I remember pulling into the parking lot outside of the building. I stepped out of the car, looked at the building, and expected to feel disdain for it — but instead felt a small pang in my chest. It was the way you’d feel if you saw an old friend you hadn’t seen in years. The sights, sounds, and smell are familiar and yet so different.

As I stepped out onto the parking lot — the same parking lot where my dad taught me how to ride a bike, and my cousins and I would try to light weeds on fire with a magnifying glass — that pang deepened into an ache.

The restaurant and this building I was about to go into for the last time was where I learned to walk. It was where I learned to talk. And now I had to say goodbye.

I remember walking through the kitchen, greeting the workers there that I knew and had grown up knowing. The surrogate mothers and fathers and uncles and aunties who were always quick to smile and make me a meal if my parents were busy. I made my way through the door where I bumped into my uncle so many years before and had a bowl of pho dropped on my head.

I remember standing in the dining room for a moment to just take everything in—the waitresses and waiters serving customers their orders, the near constant ring of the telephone for deliveries, the shouts from the kitchen.

This was where I spent long evenings watching the sun melt into an inky darkness out the window while waiting for my mom to finish the dinner shift. It was where I learned to read from hand-me-down chapter books from my cousins — The Magic Tree House, A Series of Unfortunate Events, and Harry Potter. There were bad memories here, yes. But there were so many happy ones too. Their alchemical mixture formed me into the person I am today, for better or for worse.

More than anything, though, the restaurant was a place that I learned to love and hate the same way you would your family — where the love is unconditional but the hate is anything but. As my eyes swept through the dining room, and I fought the lump building in the back of my throat, that’s when I saw it: My old table. The one I used to sit at with my brother and cousins.

The table where I spent my days drawing, studying, reading, and waiting for my turn to bus tables. Our little pocket of the universe back when all that mattered was your family around you and what you were going to have for dinner. And there was a kid sitting at it.

She couldn’t have been any older than 11. Judging from her backpack at her feet and the stack of folders on the table in front of her, she just finished school. But if she had homework, she wasn’t working on it. Instead, a sketchbook laid open in front of her as she concentrated on a picture she was drawing. I went to a table where one of the waitresses sat folding napkins and asked, “Hey, who is that kid?”

She looked up from her napkins and quickly glanced at the table, “The dishwasher’s girl. Just finished school down the block. She’s waiting for her dad to finish his shift so they can go home.”

I smiled, because I knew the truth about that little girl sitting at the table, sketching and letting her dreams run away with her: She was already home.

Author Bio

Tony Ho Tran is a writer and former restaurant kid whose work has been seen in Huff Post, Playboy, Narratively, and wherever else fine writing is published. He currently lives in Chicago where he regularly calls his mom for advice when cooking Viet recipes.

Tony Ho Tran is a writer and former restaurant kid whose work has been seen in Huff Post, Playboy, Narratively, and wherever else fine writing is published. He currently lives in Chicago where he regularly calls his mom for advice when cooking Viet recipes.

After reading your story, which parallels mine in ways I’ve never dared to hope to be true, you’ve compelled me to write of my own in my personal statement for college. I’ve received offers from several great colleges and I have no doubt that it was the right topic to write about. Something that is so complex, embroiled in a mix of emotions, it felt freeing just to put thoughts to paper. Thank you, for putting your story out there and letting the other restaurant kids know they’re not alone.

from a fellow restaurant kid, thank you for writing + sharing. got me crying bright and early in the morning.

I really appreciate the well written personal story about growing up in the restaurant business. We all need more understanding of others’ journeys. Da Kao is a favorite. Thank you.

What a lovely story and it was beautifully written. I was hoping the story would not end. I’m looking forward to reading the author’s other writing.

I love da kao. the new owner has boss printed on orders she takes. i found that off-putting. combination fried rice, fresh spring rolls with fish oil dip and pepsi with no ice. i tried to sit at the old newspaper booth where we always waited for to go orders and read the paper. she asked me to go wait in my car. the poor guy after me had no air and it was hot out. Me and my husband just ate there inside, also. I feel it still tastes the same. Maybe smaller portions? Is your dad still delivering there? I swear I saw him in a new little car. He yse to just walk into my house lol. Did the lady from Hunan palace buy Da Kao? That place has msg. Love the legacy your family built.

I was born and raised in Sioux City but haven’t lived there for 40 years. When I’d go back to visit my parents a trip to DaKao was always on our menu.

We are in an era where the local independent restaurants are being squeezed out by the big corporate restaurants. Yes, the food at one of these places in Tampa may be the same as the one in Kansas City. What you gain in consistency you lose in not having the owner greet you by name and genuinely appreciating your business or seeing the restaurant kids doing homework between clearing tables.

Great piece!

The past becomes one’s full circle as it opens a new circle for another to travel.

I would like to feel more of what you are sharing.

DaKao #2 pho and fresh spring rolls all day long…literally my favorite meal on the planet. Thank you for this beautiful story and a look at what it was like for you.

I’ll have number one, two spring rolls and a diet Pepsi. I can’t tell you how many times I ate there with my wife and daughter. The food was always good. I loved, still do, pho. Funny thing, I spent a year in Viet Nam in the late 60s as many a young guy did and don’t remember eating it. I’ve even tried making pho myself but there must be a secret ingredient because it was not nearly as good.

Beautifully written Tony! Thank you.

I lived in Sioux City 40 =years of my 82 year old life and remember boys sitting at that table doing homework. One of them was probably you. I loved DaKao, loved the people and the food. At lunch there with my friend many times and dinner there with my family. Every time my kids came back to visit, a trip to DaKao was on the menu. Maybe more than one trip. Thank you so much for your story because it brought back so many memories for me.

I’m a writing teacher and certainly appreciated your work. I hope you keep writing. Thx for sharing.

Great article Tony! We are all so proud of you at Bishop Heelan! (Da Kai is my wife’s favorite)

Very touching, I felt anger and happiness as I knew how this is a true story. We ate there many times over the years we were there. We also raised our children in restaurant style and today they are wonderful people and great parents,most of all hard workers,true to their employers.

Very well written. Our family has eaten at Da-Kao many times over the years. My wife and I continue to do so. Now, whenever our daughters come home to Sioux City for a visit, they insist on eating at least one meal at Da-Kao.

Beautiful story! Beautiful face!

What an amazing writer you are. I remember going there many times over the years. And ordering food to be delivered. Being allergic to MSG the food was always made MSG free. I knew I never had to worry about it.

So sorry to hear that they sold it. They did an amazing job being one of the best restaurants in Sioux City.

Can you please write a book about being a restaurant kid?

Wow. Beautifully written. Honest and heart-filling. And we remember The Restaurant so well. A friend from Gateway introduced us to it and we were hooked. Our son (at 18 months) was happiest eating there and at our favourite Mexican place and we always ordered Moo Goo Guy Pan with extra mushrooms so he could eat the mushrooms. Thank you for this story.

No question, my favorite restaurant in SC and still hard to beat compared to other Viet food I’ve eaten in my hometown of Portland, OR and elsewhere. But this is a fine and moving article. My family didn’t own a restaurant but my mom waited tables most of her life. I remember sitting in a few of them drinking pop, reading a book, waiting for her shift to end. Thank you very much for this lovely, poignant essay.

I’ve only been to DaKao a couple of times, but this makes me want to go back…when the whole COVID thing is over (someday!) Beautifully written.

All these stories in this article are familiar. I wasn’t ever at “The Restaurant” as Jenny always referred to it, but always heard about it. Reading this and remembering my childhood with Jennifer as my best friend! Very well written! ❤️

I love eating at DaKao restaurant’s. From back working @ Gateway 2000 computer’s. At some given given day during lunch breaks, there would about 10 tables or more from GW2K dining at the same time .. I’ve preferred the Tran’s recipes though vs the new owners. So glad that they’re staying under the same name though. I knew the original owners and their Kids (all grown up now). Very nice story, well written.

Beautifully written.. Have been eating there for several years.. Love it.. Sorry your family sold it..

I ate there the first week that it opened. My first dish was ginger chicken. the food and service was always great. I remember the author riding his hot wheels trike around the restaurant. What a great memory he has written!

Wow! Love it! Beautiful story ❤ you are for sure an inspiration!

My favorite restaurant in Sioux City! I remember you taking my order many times (#32, spring rolls, hot tea) and always being charmed by your reading materials and subtle existential dread. I am so thrilled to read this wonderfully written story and plan on sharing it with others. I’m so happy you are doing well and living in an exciting city!

I used to have sleepovers there with Emily. She was one of my best friends growing up

I didn’t grow up at DaKao, but have spent many many hours there enjoying the food and the people. Easily my favorite restaurant (#30 with Chicken, order of fresh spring rolls, hot tea please.) We went there to celebrate when our kids got good report cards at Heelan, or for quiet political meetings. I don’t recall seeing Tony, but I do have clear memories of his dad there. Today it has changed: the interior was beautifully remodeled just before the pandemic hit and we had one great meal before things changed.

Tony’s story sounds like so many immigrant stories. Our community is so much better because the Trans, the Nguynes and so many other families came here to make new lives. Thanks, Tony – great writing.

Oh my! This narrative takes me back…back to the days in the 1990s…when my dear friends, John and Karmon Amsler, would meet there every Monday night following our daily volunteer gig…tutoring young Southeast Asian (mostly Vietnamese) at ST. Thomas Episcopal Church. We did that routine for about ten years. While the tutoring program eventually faded…our love for that eatery did not. Yes, we watched as the the “restaurant kids” did their respective thing under the watchful eye of relatives. Little did we know until now “the rest of the story.” Thank you for sharing such an honest portrayal of what it was like. May you always treasure those memories!

Beautifully and poignantly written, tugging at the heartstrings for so many reasons. Da Kao is one of my absolute favorite places to eat in Sioux City. Your family(for all you years of sitting at the table), has done a phenomenal job.

Loved this restaurant and always noticed that special family table. What a wonderful writer you are.

I have eaten at this place for years. I knew it was sold the minute the Crucifix was gone. The food is fine but not nearly as good as it was before. Thanks for sharing the view from you table.

What a great story! The story was written so beautifully that it came to life! I could see through your eyes and imagine myself there. What a great read! You are well on your way Mr. Tran!

Shop baby as well , mines a corner nail station in the way back where no one ever sits, the grave yard for gel machines that seen better days..

A nostalgic story beautifully done. . I eat in Vietnamese restaurants in Vancouver, Canada, all the time, and was touched to see it through the eyes of a little person who doesn’t just eat there but lives and grows up there. Thank you.