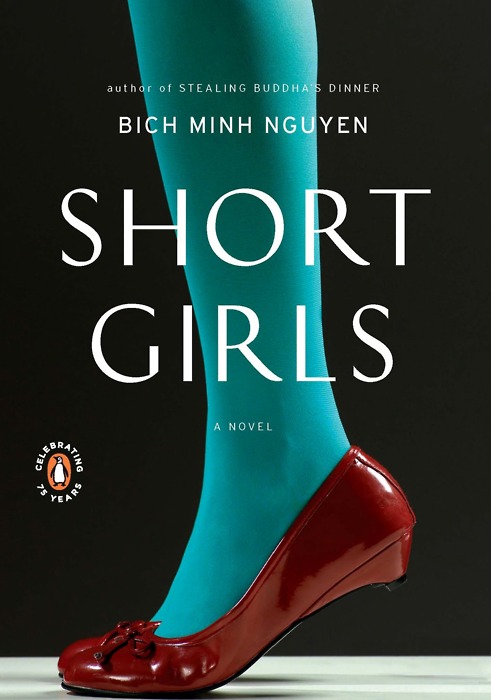

Using Vietnamese height – or its lack — as the explicit metaphor for Vietnamese experience in the US, Bich Minh Nguyen’s debut novel Short Girls explores how one family plays out insecurities, disconnection, and doubt.

Have you subscribed to diaCRITICS yet? Subscribe and win prizes! Read more details.

In the novel two daughters try to figure out how to relate to their widow father who is plagued with doubts that include the injustice of being too short for American success. Such a formula, advanced height = success, leads the father to perpetually lament a life destined to fail in a country where stature is vaunted and weakness, or shortness, is harpooned. How unsurprising then that his daughters, Van and Linny, struggle with feeling not quite good enough.

The refugee parents settle in Ann Arbor, Michigan, far from contemporary fiction’s preference for the Vietnamese American dotted landscape of sunny California. Instead, they live in a mostly Anglo (and taller) Michigan surrounding. This leaves them to a sharpened experience of difference that seems to cut especially in just the way that loneliness can salt the wounds of insecurity.

Van is the older prodigal daughter who has learned the lessons of dutifulness so well it has become her whole sense of self. Throughout the novel she is described as a shell, her character shuffles about in a haze of self-alienation. It eventually is enough to make her wonder what her husband was thinking when he married her; who was it exactly that he thought she was? When he unceremoniously announces his wish for a separation, Van is numbed with rejection, but then comes to the realization that the seeds of alienation were planted not just in their marriage, but within her very sense of self. For Van, one common self-distinction is how resolutely non-distinctive she actually is. With a look in the mirror, Van assesses: “The reflection was accurate, telling her, she was the same plain, short girl she had always been.”

Linny is the younger daughter, shorter than Van – height observations are a premium in Short Girls – but less plagued with self-doubt though she struggles with an equally persistent sense of alienation. Though she has not succeeded in the typical immigrant narrative, Linny seems more aware of her value. She evades the moral compass that has harnessed her sister and proudly makes use of her Asian woman cultural caché. Her dissolute lover is a married white man who has a very tall wife. For reasons of her own, she finds this set-up very savory in its unsavoriness.

The sisters never feel connected to each other in their adulthood, both feeling judged by the other and neither feeling particularly connected to their parents. When their mother dies unexpectedly, the girls make gestures to care for a father who seems haplessly enthused only when he is caught up with his home-made inventions, especially with his “Luong Arm” (an eponymously named reaching tool). With dreams of entrepreneurial empire in his eyes, he absconds to his private short-people emancipating oasis (the basement) where he perfects his many inventions, patents pending.

So how does this novel fare in its keen interest in the role of the Vietnamese father in the lives of his American raised children? Short Girls doesn’t hedge around its metaphors. All throughout the novel, the patriarch Dinh Luong puts his frustrations – we can insert the traditional tropes: challenged masculinity, minority alienation, generational disconnect, cultural marginalization—into his passion for the Luong Arm and other supplemental contraptions meant to make life around the house easier for shorter Americans who don’t quite conform to the traditional home architecture. His fixation on the limitations of physical stature may be less of a concern for his female children, Linny makes frequent comments about the cultural desirability of diminutive exotic Asian women, but height nonetheless punctures into both daughters’ sense of self.

“Van believed she wouldn’t care so much about being short, wouldn’t continue thinking about it still, if the subject hadn’t always consumed her father. But it was the one thing he liked to talk about, the one thing she could get him to talk about. His pronouncements at the dinner table—about how short people were discriminated against, and how short people had to work extra hard to get good salaries and respect, well, these did seep into Van’s thoughts.”

Vietnam rests in the background like a surly relative who only becomes disarming if you pass him a couple of sloppy drinks. Neither daughter wishes to visit and puts their mother off each time she suggests they go, but they assuage her with their guilty oh-wouldn’t-it-be-nice-one-day-but-not-now platitudes. The family’s grievousness stems from life in the US the novel suggests. To that end, I enjoyed this novel very much. I could imagine the quaint politeness of a midwestern metropolitan area. There are a couple of dramatic and spunky youdonemewrong scenes as well as humble moments where someone recognizes their own moral weaknesses that provide satisfying character study. Those moments usually involved romantic pairings. The relationship between parent and child remains somewhat formulaic. When parents and children only speak and think in terms of duty and guilt, readers lose the richness that comes out of ambivalence and ambiguity. Moments of disconnection set against the subtle observations that children make regularly about a quiet moment, a tender touch, an unexpected smile, those are the moments that seem harder to come by in fiction about Vietnamese fathers. Perhaps I am being nostalgic for a more nuanced portrait of a paternal figure, like we get to see in le thi diem thuy’s lyrical and haunting The Gangster We Are All Looking For. Or perhaps that is the invitation, to keep looking for him.

–

Cam Vu earned her doctorate in American Studies and Ethnicity at USC where she focused on cultural work in the Vietnamese diaspora. Her book project focuses on affects in diasporic communities. Among other things, she loves to write about food.

Bich Minh Nguyen is a Vietnamese-American novelist. She won a 2010 American Book Award, for Short Girls and received the PEN/Jerard Award Fund in 2005.

Bich Minh Nguyen is a Vietnamese-American novelist. She won a 2010 American Book Award, for Short Girls and received the PEN/Jerard Award Fund in 2005.

Do you enjoy reading diaCRITICS? Then please consider subscribing! See the options to the right, via feedburner, email, and networked blogs.

Please take the time to rate this post (above) and share it (below). Ratings for top posts are listed on the sidebar. Sharing (on email, Facebook, etc.) helps spread the word about diaCRITICS. And join the conversation and leave a comment! Like Van and Linny, do you also struggle with insecurities that seem to prevent you from achieving success? What are ways in which the Vietnamese community can resist these insecurities?