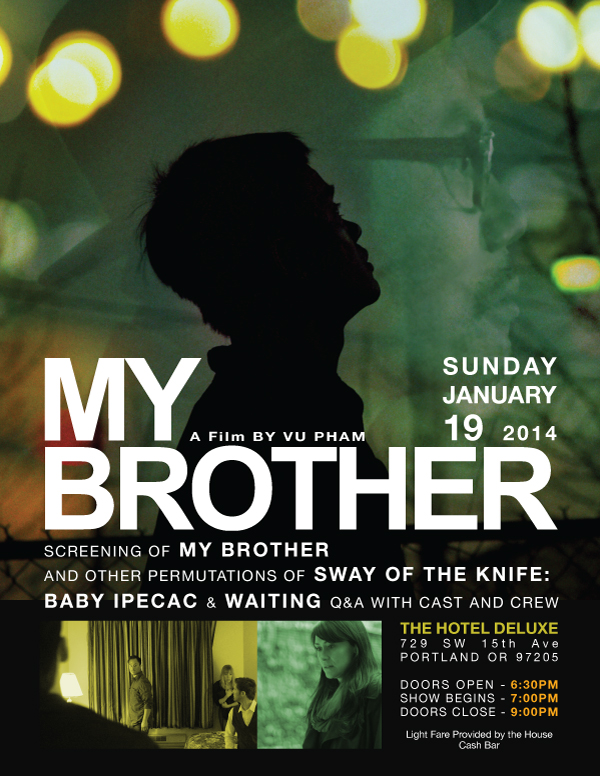

Dao Strom interviews Vu Pham, a filmmaker, writer, and actor. He is the founder of nomenstatua, a film production company. His latest, “My Brother,” is an experimental narrative short film which he received a Regional Arts Cultural Council (RACC) grant for in 2013. Pham is currently in development on a feature-length film, Sway of the Knife. As an actor, Vu Pham has appeared in ‘Extraordinary Measures‘ (with Harrison Ford and Brendan Frasier) and ‘COG’ (based on a David Sedaris story). “My Brother” will have a debut screening on January 19 at Hotel Deluxe in Portland, Oregon.

Have you subscribed to diaCRITICS yet? Subscribe and win prizes! Read more details.

The long shadows of inherited cultural trauma. The ghosts of past violence, un-remembered yet still felt. Lost/surprise siblings and scattered/absent parents. Being Vietnamese but managing somehow not to associate with many others of our kind: being outsiders. These are some of the things I find in common with Vu Pham when I first sit down to talk with him. We met initially when he reached out to me on Facebook, on the recommendation of a mutual friend, Andrew X. Pham.

Vu Pham is a filmmaker, writer, and actor. He was born in Vietnam but grew up in Oregon from the age of 6. His current project, My Brother, is a short experimental narrative film centering around a Vietnamese-American male protagonist who has a strained relationship with the titular “brother” in his life—a brother who wanders the streets, mumbling and sometimes cursing, in Vietnamese and in broken English, asking for money, at times asking for help, who may or may not be homeless, and who appears mentally unstable. Sometimes when Michael, the protagonist, sees Khanh, his possibly derelict brother, on the street, he ignores him. On occasion he even goes as far as denying that he knows him. These scenes create a poignant contrast to the snippets of scene in which we witness Michael first being introduced to Khanh by the father they share in common, and Khanh politely pours tea for them all, and tells Michael how happy he is to meet him.

The interaction between the two half-brothers—the degree to which Michael can or cannot “assimilate” Khanh into his own life (and, perhaps, self)—lays at the heart of this film for me as a viewer.

Also, the way that peripheral characters (mostly non-Vietnamese) treat and react to the brother when he wanders into their spaces, and the way that the viewer, as audience member, is stuck in the position of spectator to these interactions, makes for a provocative, sometimes discomfiting, viewing experience.

If I might make a personal digression here… I also have – or had – a half-brother. I have a father whom I grew up believing had died in the war, a perfectly acceptable story and death, but then who (I was informed when I was 14) turned out to be still living in Vietnam. He spent ten years in the Communist reeducation camps. He was already married; my half-brother was a year older than me. I met this father finally when I first returned to Vietnam, at 23. My father’s family welcomed me into their lives; they were (and have been) always kind and gracious toward me. I did not know my half-brother too closely, but I felt connected to him. Eventually they emigrated to the States. Today, my half-brother is no longer alive. The story of his death (which I won’t go into detail about here) is marred by tragic circumstances that the true source of—psychological or otherwise—may be hard to pinpoint. You might blame it on issues of mental health. You might blame it on what the Communists did to that country and what children like my brother had to grow up in—what children like me, who left, escaped. Or maybe you might say someone like my brother did not ultimately have what it takes to assimilate and survive, to make it all the way across the abyss contained in that little hypen between “Asian” and “American” in the term that grants us our new identity: Asian-American.

Suffice it to say: there is a wayward “brother” wandering the shadows of my story as well.

And maybe it is so for many of us.

Be it a literal brother or not, or just some experience—some awareness—of lost-soul. Of the cost of what lies behind. A painful reminder we don’t want to look at. An emotional outburst we ourselves are never going to have, because we’ve learned how to properly repress or rid ourselves of it, whatever it is.

These may or may not have been Vu Pham’s intentions with My Brother, but these are some of the impressions viewing it stirred in me.

The film’s aesthetic style is also notable. Much of it takes place at nighttime. Neon signs, a lit-up boat, some graffiti on a wall, provide splatterings of brighter color here and there. Reflections in storefront windows play a part. The editing is often fragmented and disjointed, with sometimes rapid, sometimes slowed-down sequences of images. We see glimpses of street life in Vietnam, fishing nets unraveling from a boat, lonely Portland streets, a night-lit foot bridge, terse encounters in the mundane everyday world of cafes and bars and artist studios. A story emerges—of an elusive, broken relationship—but it does not run in a straight line. It does not try to fit itself into a typical narrative structure (read: Hollywood). It does not explain itself or end in pat resolution. As it unfolds it builds its own construct out of its personal subject matter and style. It makes its own way. It is an ambitious work that resonates with the integrity and intensity I have come to know as integral to who Vu Pham himself is as a person and artist.

Each time we sit down to talk, inevitably Vu and I enter into territory with shifting boundaries and plenty of questions, regarding identity, media, representation, cultural positioning, aesthetics, Asia-America, and the implications and expectations of the “immigrant experience.” Here, preceding the debut screening of his short film “My Brother” (to be screened alongside two other shorts, “Baby Ipecac” and “Waiting,” also by Vu), I presented Vu with these questions in particular:

DS: I understand there are autobiographical elements in this story. Can you tell us about how autobiography intersects with artifice in the inspiration behind the story and characters of My Brother?

VP: I generally find myself gravitating toward experiences and memories—profound or mundane—and then shaping them into fantastic creatures for the sake of drama. This is how I’ve worked as a storyteller for most of my creative and professional life.

Specifically with regards to My Brother, I was greatly inspired by actual experiences with a half-brother. He is the basis of the story and the foundation for the character, “Khanh,” who is played with virtuoso by a non-actor, Mr. Long Nguyen. My real half-brother was someone I met in 1994. He had just immigrated to this country with my father, mother, and three other siblings.

My father was in a Communist Reeducation camp in Vietnam for ten years following the end of the war. I met him once in Vietnam when I was maybe four or five and then didn’t see him again until his immigration to the U.S. He sought me out when a friend of his showed him an article of me in the Oregonian. I was featured in a Thanksgiving story on the redemptive journey of the Vietnamese immigrant, ironically enough.

DS: For you, what is this film really about? And what has the making of it given or taught you – either aesthetically or personally, or both? Is this in any way a cathartic process for you?

VP: The making of this film has been a truly cathartic experience in many ways. I have often said with regards to the feature film narrative that this is inspired by, Sway of the Knife, that I am composing a love song to the outsider. I believe that for My Brother, this is still true. It is a poem of loneliness. I’ve grown up (and to some degree, still do as an adult), dwelling in the amorphous, alienating spaces of personal and cultural ambiguity. Every human being can speak about alienation and loneliness but my particular circumstances were centered around the boat refugee experience, the cultural assimilation to the U.S., the tragic and violent death of my mother shortly after emigration, the fall from the fiery crucible of my war-traumatized, tyrannical uncle’s domestic reign, and the accumulation of these forces that shaped me as I struggled to “know thyself” in youth within the “Vietnamese-American” landscape.

My Brother is an impressionistic piece that sifts through the thorns of identity from the perspective of a Vietnamese-American man whose social consciousness is arguably more Western than Eastern. To a large degree, I am that man. And that man is, in effect, a persona of the Everyman.

The half-brother character, as you’ve so astutely observed, is a reflective doubling of self. While he is “Khanh,” a man of flesh and blood outside me, he is also me. “Michael” knows the levels of truth to this ontological and psycho-social connection all too well and it is his own knowledge that he ultimately runs away from; disavows. This is not to say that the conflict between the two brothers is purely metaphorical because that would be to cowardly hide in the shadows of cerebral monism. Their relationship and their individual struggles are real as cultural clashes, mental illness, social alienation, and drug addiction are real.

The process of making this film has helped me to better understand myself. Being the ultimate cynic, such a statement about the artistic process is generally scoffed at but I cannot be more sincere when I say this. Now did I set out to make a film with such “noble” personal intentions? Absolutely not. I do not believe that making art is necessarily any more enlightening than working in a chicken egg factory and those who would so arrogantly presume that their poem, painting, or film is somehow more valuable to the human experience than another individual’s 35,000 eggs that he or she sorted through on the line, is the kind of “artist” that gives a bad name to artists everywhere. Enlightenment and meaning is here in every breath for every person. They just have to take it.

I will say that my choices to seek out the most complex form of play (filmmaking) as a means of revisiting my personal history on the grounds of artifice has compelled me to take pause. In that stillness of contemplation, I’ve seen more sustained, more whole reflections of myself in the broken stream of life.

DS: Your filmmaking style is decidedly unconventional. Can you talk about your aesthetic approach and editing style? (I.e. Why not just tell a straightforward story? Why not just edit your scenes in a more traditional narrative fashion, to make the story more accessible to an “American” audience?)

VP: People’s questions about my film aesthetic are always interesting to me personally because they will often identify my style as being “experimental,” “artsy,” “esoteric,” or “foreign” even. The last one always piques my curiosity since I’m about as Western in thought and behavior as one can be. Do they pluck that word off the tree of classification because I look “foreign” or “exotic”? Perhaps.

Certainly I recognize that my approach to filmmaking is unique compared to the mainstream but I secretly wish that someone would one day come up to me and say, “Hey I just watched your so-and-so film yesterday and it reminded me of how I totally experienced ‘xyz.’ When John Doe was walking along the street and suddenly he was in a sandstorm in the desert surrounded by cartographers circumambulating him on stilts with crazy masks….”

My point is that my methods are simply my efforts to replicate what I perceive to be the fundamental everyday consciousness which is non-linear, fragmented, quantum dynamic, and in short, pure chaos. Our brain, as a reducing valve, protects us from the churning sea of chaos that surrounds us.

I do not believe that people experience, remember, and act in the world in tidy compartments that are clearly defined as ‘A, B, C’ or “here and there,” “inside and outside,” or “today and yesterday.” I believe that those are categories of bio-social functionality which is the known language of life and falsely presumed to rest at the top of a hierarchy of consciousness. However, existence is a dark and complex abyss of Being wherein we are swimming in (and sometimes drowning in) the confluence of memories and actions. While I may be “here” and acting in the “now” a part of me may be wandering in the canyons of another time and place, and while I may comfortably assume that my behavior is resultant of reason in its tidy calculations, perhaps it is really a bi-product of something else further from the reach of reason. This existential reality is simply being alive, but to be fully aware of one’s own existence in this way would mean to be crushed by the excruciating weight of total self-consciousness—an impossibility of course due to the nature of biological design.

I’m the kind of sick bastard that likes the terror behind those doors where chaos swirls because I think it’s exciting and, occasionally, it’s fun to crack open the door and allow some of that to come swimming in—ya know—to keep it real. So really my “unconventional, weird, artsy, and foreign” film aesthetic is just me trying to mimic what is happening right now all around us to everyone. No big deal, right?

DS: What else do you want to say about the position of Asian-Americans in the media? As a filmmaker and writer? As an actor?

VP: The position of Asian Americans in the media is a tough nut to crack. It makes me dizzy to even begin to speak about the elaborate maze that is our socio-politics, history, and cultural manifestations past and present. You could say I take an anthropological approach (as amateur as it may be) when it comes to dissecting the current position of Asian-Americans from both an etic and emic perspective. Additionally I’m greatly influenced by dialectical materialism. What comes out of this particular lens of thinking is generally something that people will find to be uncomfortable, sometimes politically incorrect, and possibly infuriating. Perhaps in answering your questions in a very general way, I’d like to counter-point with a series of questions that are thought experiments personally important to me. Please understand that my area of interest would be specifically Eastern and Southeastern Asia as I believe that the ethno-cultural specifics pertained therein are appropriate to my theoretical musings.

What did the devastation of Nagasaki and Hiroshima by the two atomic bombs, “Fat Man” and “Little Boy,” do to the collective self-consciousness of the Japanese people and how has their continued relations with the U.S. and the West as a whole affected this? How has this impacted other Asian cultures if we are to presuppose, for the sake of argument, their predominant Asian representational power—the perceived “face” of Eastern and Southeastern Asia?

How have the concurrent historical traumas of Asian countries/cultures such as China, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Japan in the 20th Century shaped the “immigrant experience” and henceforth their self-identities in the United States? Furthermore, what can be said of the dense concentrations of emigration/immigration of Asian peoples to the U.S. and how has it impacted their social behaviors, namely the pragmatic practices of assimilation?

Does the physical difference of Asian peoples play a role in their self-perception in the U.S., especially as represented by media, and does it play a role in the U.S.’s perception of them? Is there a connection between physical difference and behavior? As in, and this may sound archaically dangerous in a pseudoscience eugenics-phrenology kind of way, but are people with smaller frames more apt to behave passively when surrounded by those who are larger than them?… I know, I’ve got some gall, right? “What are you saying? That Asian people are wusses?” And this is precisely why my intellectualism is for a limited context and so I’ll shut up here.

DS: Who are some current Asian-American icons who interest you: who do you like? who do you hate? who do you think is a “sell-out”?

VP: Wong Kar Wai, Park Chan Wook, and Ang Lee are a few Asian directors who are hugely inspiring to me.

I do not like Asian entertainers who seem to have an insatiable need to “perfect” their characterizations/impersonations of Asian stereotypes replete with facial features, voices, and accents, through nauseating repetition. It was funny when They did it to us for some mysterious reason (which I can accept as simply “funny” without the need for explanation) and it was funny a couple of other times when we mimicked their behavior as a “counterpoint” (?) but now it’s not only NOT funny, but causes me to question the respective entertainer’s sense of originality, the current state of affairs being that it is a prodigious “act” in the world of entertainment, and, that being said, I question their relationship to the almighty dollar. In the end, that process of questioning leaves me with little respect for those who not only refuse to question this self-created playback mode (at the behest of the master), but who seem to shit on this perfectly legitimate argument by continuing to be a broken record that occasionally releases a strange sound akin to bleating sheep.

DS: I understand you are developing a feature-length film, Sway of the Knife, that will explore similar aesthetic terrain and subject matter as My Brother. What are your plans and goals for Sway of the Knife?

VP: Sway of the Knife is currently in the financing stage of development with some very plausible avenues for funding. We’ve been speaking with some actors who we know will help this film to be funded through their “star power” as well as film investors who are interested in its potential success as a breakout American independent film.

The story of the brothers is fleshed out in Sway although there is still a lot of mystery and ambiguity involved. Like My Brother, its film aesthetic is unconventional but needless to say, with an additional 80 minutes of story time, the emotional connection to the story and characters is more accessible and the narrative is more rich and complex.

For a full synopsis of the Sway of the Knife, please visit this link below.

http://swayoftheknife.com/investor-packet/

DS: How do you stay “true” to yourself as an artist?

VP: I go with my gut, ask a lot of questions, think a great deal about things, stumble often along the way, forget, remember, and then forget again.

*

Sway Trailer from nomenstatua on Vimeo.

_

Vu Pham is a filmmaker, writer, and actor. He is the founder of nomenstatua, a film production company. His latest, “My Brother,” is an experimental narrative short film which he received a Regional Arts Cultural Council (RACC) grant for in 2013. Pham is currently in development on a feature-length film, Sway of the Knife. As an actor, Vu Pham has appeared in ‘Extraordinary Measures‘ (with Harrison Ford and Brendan Frasier) and ‘COG’ (based on a David Sedaris story). “My Brother” will have a debut screening on January 19 at Hotel Deluxe in Portland, Oregon.

Dao Strom is the Oregon-based author of the the novel Grass Roof, Tin Roof and the short story collection The Gentle Order of Girls and Boys. She is also a musician with two albums, Everything that Blooms Wrecks Me and Send Me Home. More info here.

Do you enjoy reading diaCRITICS? Then please consider subscribing!

Please take the time to rate this post (above) and share it (below). Ratings for top posts are listed on the sidebar. Sharing (on email, Facebook, etc.) helps spread the word about diaCRITICS. And join the conversation and leave a comment! What do you think of Vu Pham’s film? Like Dao Strom, did you also find yourself drawn to the film’s exploration of identity and assimilation?

____________________________________________________

A great interview that covers lots of territory Dao.

Vu, your comment about phrenology really hit home. Having a son just go through adolescence while in the American school system (albeit in Singapore) really hit home how hard it is to be a smaller framed Asian boy in an American environment. My son has lived in Asia all his life with 2 Asian-featured parents. Yet, one afternoon, he came home and told us he wanted to change his Vietnamese middle name Trung to David! We had a talk about cultural identity, diluted perhaps by our assurances that no one looks at your middle name anyway. It was with relief and sadness that I received his observation about the Asian movie King Runrun Shaw’s death last week – “It’s interesting, Asians can make it big in the movies.” ;(