The following essay was commissioned and subsequently rejected by the Carnegie International, 57thedition, exhibition, which opened at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on October 13, 2018.

The initial email from the Carnegie International stated, in part: “I am commissioning a series of essays based on my five major research trips. Each trip was taken with a curator colleague. Our trip becomes the point of departure for a new piece of writing by an invited ‘armchair companion’….Our itinerary [in Singapore, the Philippines, and Vietnam] was prompted by… [my curator colleague]’s interest in the colonial imprints of Spain and France on the contemporary culture.”

This is from an email that I received after my submission of the essay: “Thank you for your hauntingly beautiful ‘travelogue’ and for your voice of post-colonial criticality, which is crucial to our project. I am reaching out to you with a concern, however, about your interpretation of the unannotated and perhaps misleading portfolio of images—that is, it seems there has been some misunderstanding regarding…[the curator]’s approach to her travels in advance of the exhibition and the ethos behind the organization of the exhibition…Her intention in traveling was to find interlocutors and extend dialogues, to consider a back-and-forth movement and an expansive conversation, not to seize or appropriate specimens. This is why she, among other things, invited fellow curators to travel with her—and invited writers like you to ‘translate’ these travels through additional lenses, to build webs and layers of narrative. Her objective has really been to bring the whole premise of the ‘International’ to debate, which is why she was extremely interested in your particular voice. I am afraid that publishing the essay as is would be to compromise, even negate, that position and also skews…[the curator colleague’s] participation.”

Presumably, another writer has now been approached and will soon deliver another “imagined travelogue” for inclusion in the exhibition catalogue and online. If so, then I invite you to compare the two essays. I think it is instructive to understand the parameter of what is deemed acceptable and unacceptable when it comes to “companionship” and the “imagined.”

The commission came with a “dossier” (their word, not mine) of 199 photographs, taken or provided by the two curators, whom I identify below as “Curator I” and “Curator M”. I had chosen some of these photographs to be featured as part of my essay. They would have appeared in pairs, though not always, side by side and of equal size. Below, I provide you, instead, with a description of what I saw in these photographs, and you can imagine them for yourself because no one can curtail our words or our imagination.

-Monique Truong

[Editor’s note: As of this essay’s publication date, we observe that there has not yet been a Carnegie International “Travelogue Series” essay for Singapore, the Philippines, and Vietnam posted to the Carnegie Museum of Art blog.]

–

All journeys are composite acts of the imagination.

Our traveling companions are myths, fantasies, History as we have learned it, and other compelling fictions, such as the idea of the self.

We believe that we travel to see something truer, a glimpse of a rare bird. There it is! The blue tail feathers, the yellow body, a white orchid in its beak. We travel because we believe that there is truth to be seen. We are creatures of such faith, the rarest of birds.

All journeys do not end well.

Genocide, slavery, colonialism, and consumerism. These are also acts of the imagination.

We celebrate what we have acquired and call them spices, precious metals and gems, slaves, and other bargains and steals. For the lesser baubles, the ephemera, and items with only sentimental value, the French gave us un souvenir, the Spanish el recuerdo, both from the verb “to remember.”

So, let us never forget.

All journeys are a culmination of prior ones taken.

I seek only art, you may say. I acquire not to possess but to share.

The “only” is impossible here. The “I” is always a “we.”

There is the decision to go.

There is the decision to go.

For the purposes of this imagined travelogue to the Philippines, Singapore, and Vietnam, we are Spanish, Portuguese, French, British, and American. We are a lot of men.

We are two women, you may say. We travel within our own bodies, not anyone else’s.

What is a body, Curator M and Curator I?

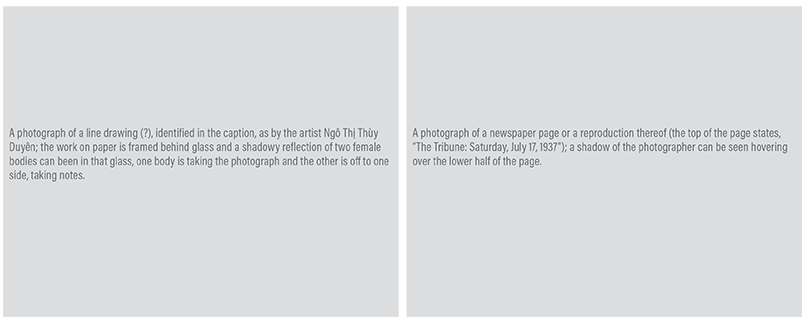

Among the 199 images included in your “annotated digital dossier,” I do not see you, except as a reflection or shadow upon the glass of a frame or a vitrine of a museum exhibit.

So, I imagine you:

The bones, the muscles, and the skin.

The education, the opportunity, the power to see or not to see, and the institutional privilege to declare what is rare and what is common.

In your hands, a Mexican passport and a U.S. one, respectively.

We are on a research trip, you may say. Not a pleasure trip, no selfie sticks. We are there to see, not to be seen.

We travel en masse.

We travel en masse.

History is a cruise ship, discharging its waste into the oceans and the seas, disgorging its passengers, a horde at every port.

We are curators, you may say. We are the opposite of the horde.

There is the decision of where to travel, which is intertwined with the why of the journey.

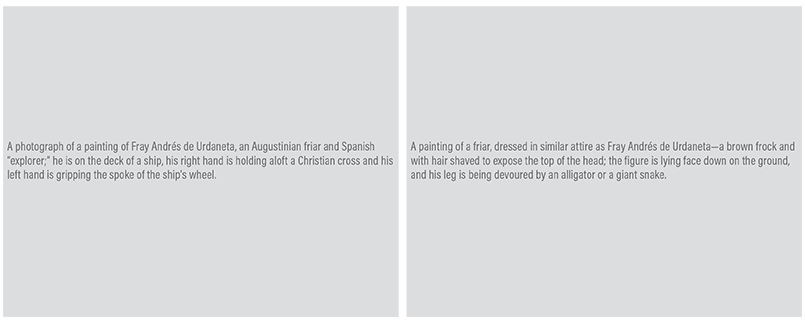

The aforementioned men had God in their hearts and Greed in their souls. They mistakenly believed—many beliefs are mistakes—that the former would justify the latter. They made a Devil’s Bargain with God.

We all lost.

The men left their names and their DNAs all over these countries—the Philippines, for goodness sake; the surname Raffles is synonymous with the luxe life in Singapore; and Vietnam, my country of birth, how well you have scrubbed away the French colonizers’ names only to festoon your streets with American ones, McDonald’s and Starbucks, with more to come.

The where is really a question of where first?

Among the lot of men, to be first was to be not a traveler but an explorer. The explorer was himself a god. He possessed, he named, he culled, and he catalogued.

Our itinerary is shaped by an “interest in the colonial imprints of Spain and France on the contemporary culture,” you may say.

Imprints or footprints?

Interest in or replication of?

Contemporary culture or museum exhibits?

Curator M and Curator I, where are the other bodies? The Filipinos, the Singaporeans, the Vietnamese ones?

In your image sets entitled “Philippines (Manila mainly),” “Singapore,” “Vietnam – Hanoi,” and “Ho Chi Min [sic] City/Saigon,” there are twenty photographs of human beings or parts thereof—an arm at the edge of an art exhibit, a leg of a passenger in a jeepney, a head above a row of motorized tuk tuks in the rain—and only one photograph of a man whom you identify by name.

Tuan Mami, I imagine, is a Vietnamese artist.

We take his photograph in Hanoi.

Actually, it is a portrait. Reminiscent of the Dutch Golden Age, there is a small rectangular window of sunlight at the far right corner of the image; the foreground is in shadows; the face of the lone figure is touched here and there with the light. Tuan Mami, centered, is seated on a chair, a stack of small photographs in his hands. He is engaged in mid-speech, surrounded by round, gray-toned canvases. His own, I imagine.

There is no other identifying information provided in the dossier other than his name and his location, but it is clear to me. I am meant to presume his position as a man of note, his status as an artist. The photograph catches him in an act of speech, an instance of show-and-tell. Tuan’s gaze is directed not at the photographer but at a person or persons to the right of the photographer. Tuan, I imagine, has something to say.

Is he a rare bird, Curator M and Curator I?

The other human beings are blurs on motor scooters and torsos packed into jeepneys in Manila; two male workers—or are they artisans?—at a brick workshop in Bataan; three women—this travelogue is my act of the imagination, so we will call them artisans—at a tile workshop, perhaps in Bataan as well; a scrum of tourists at the Reunification Palace in Ho Chi Minh City; a pair at the Hỏa Lò Prison Museum in Hanoi (a.k.a., the notorious “Hanoi Hilton”), another pair in front of the Ho Chi Minh City Museum of Fine Arts, and so on.

Most are in the background: a distant figure clothed in white walking past a building located at the Bella Artes Project in Bataan. Some are merely in the way: a young man walking up the stairs and into our photograph of the ornate interior of another building, situated within this same Project.

We return home, and we tell others about what we have seen. We become experts. We write essays and books. We curate exhibitions. We monetize the rare bird, and we profit for being if not the first then among the few.

The aforementioned men killed the rare bird, stuffed it, and sent it back to their home countries in a wooden crate with other life forms similarly treated. Otherwise, how would they have proof of its existence? If the rare bird did not exist, the men did not either. History is written about those with a trophy, a specimen, a keepsake, un souvenir, and el recuerdo.

There is a moment in every journey when this desire for proof emerges in all of us, like a virus. While the camera was the cure, the camera phone is both cure and virus. Instant images, zero transaction costs, every moment and detail saved, not a thing left to the discerning eye, the vagrancy of memory, the fade of time.

We take photographs of photographs.

We take photographs of photographs featured in museum exhibitions.

We take photographs of photographs curated for their historical value. Their artistry is not the point. The photographer is often unknown or unnamed. Their subjects are now dead or near. The photographs are evidence, as in evidence of crimes against humanity, war crimes, or plain old crimes.

We take photographs of photographs because we want to remember what we did not see with our own eyes. We take them because we can. We can delete them easily, once our devices run out of memory. No trace. No cost. No harm.

The faces staring back at us were photographed first by the men who preceded us, and, now, we recreate the act. The men called it documentation. We call it context and research. The faces staring back at us in these photographs of photographs want to know whether they are subjects or objects now? They know the answer. They have always been the latter. Little has changed, they may conclude.

When we travel, we consume.

When we travel, we consume.

History, Culture, and Art, what better place to acquire these ideas, you may say, than a museum or a gallery.

This is not a question but a statement of fact because your dossier includes photographs taken at fifteen such spaces, five in the Philippines, three in Singapore, and seven in Vietnam.

From December 2-18, 2016, you visited the Museum of the Church of San Augustin, Lopez Museum and Library, Jorge B. Vargas Museum and Filipiniana Research Center, Bellas Artes Project, Cultural Center of the Philippines, National Gallery Singapore, NUS (National University of Singapore) Museum, Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore, Hỏa Lò Prison Museum, Women’s Museum, Nhà Sàn Collective, Reunification Palace, War Remnants Museum, Ho Chi Minh City Museum of Fine Arts, and Salon Saigon.

Perhaps, there were more?

What did the men who traveled there before us do, I wonder. You know, when they wanted to consume History, Culture, and Art?

They looked around them and saw no History because their arrival marked the beginning of existence, relevance, and import of these lands and of the peoples who inhabited them. The men surmised that there was Culture—primitive—and Art—folkloric—but that nothing they saw compared to their own creations, which, of course, included their God. This assessment left them with a lot of time on their hands. They became bored, homesick, and existential, even before they had devised a word for it. They suffered angst and dread along with a host of tropical diseases and dreadful sunburn. They turned their eyes skyward, but could no longer see their God because of the jungle’s dense canopy. They had to find life’s purpose, a very rare bird indeed, all on their own. So, they waged wars. They instituted laws. They built prisons. They built cathedrals, just in case their God was still there. Sometimes, it was difficult to tell which was which.

The men sent letters back home that were full of fiction, some of which were presented as fact and subsequently became History. Their imagination ran wild in thought and in action. When they behaved badly, they called it “going native.” They blamed us for everything.

Ah, you may say, who is this “us?” Different from the “we?”

Yes, different.

I belong to both.

I was born into the “us” of South Vietnam, a country that no longer exists. Now, I am a U.S. passport-carrying “we.”

When I travel to the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, I am called a Viet Kieu, which means I am ethnically Vietnamese but I live elsewhere, but really it means that I am an outsider. When I am in the U.S., I am called a racial minority, a perpetual foreigner, and I am often told to “go home.” To Brooklyn, I ask.

Instead of Vietnam, I end up traveling a lot to Italy, where there are also many museums and galleries.

Museums and galleries can provide us with History and context, but we kid ourselves if we believe that “contemporary culture” can be found there as well. A certain kind of Art, which is a subset of Culture, is found within these spaces. How we define “certain” is left to Curator M and Curator I. That is their job.

My job is to take their “annotated digital dossier of images” as a “point of departure for a new piece of writing.” I am an “invited armchair companion,” you may say.

It is always nice to be invited.

I do enjoy a good armchair, though I prefer a chaise lounge.

I am well qualified to be a companion, as opposed to a native guide, for which I would have been ill-equipped. I have never been to the Philippines, once to Singapore, and twice to Vietnam since leaving as a refugee in 1975.

But, Curator M and Curator I, did you not have one or two?

A guide, native or not, to get you from point A to point B, from Manila to Bataan, for instance.

Who is in the vehicle with you on that rainy day when you, we—this assignment of companionship is confusing, yes?—take the raindrop-dappled photographs of the jeepneys and the tuk tuks? Or on that blue-sky day when we are again in bumper-to-bumper traffic, and we snap a photograph of a crowded jeepney whose passengers are faceless, except for one school-aged girl who looks directly at us, her body sheltered by shadows except for the green-and-blue plaid of her skirt and a short sleeve of her pale blue blouse, her head appearing to float, her hand underneath her chin ready to keep it steady?

She too is a portrait, but I do not know her name.

Nor do I know the name of any individual who may have acted as your guide or, in the language of journalists, your fixer during your almost two-and-a-half-week journey.

Curator M and Curator I, are you truly alone?

According to your dossier, the answer is yes. May I say that I believe that your dossier is not being forthright with me?

None of us travel alone.

Because I do not have their photographs, their names, and faces, I imagine them.

Perhaps, in Manila there is a curator, like yourself, who has volunteered her time and her expertise or been asked to do so as a courtesy to a friend of a friend, someone whom you met years ago. She drives you to Bataan or she takes the ferry with you. She is the same age as the three young women at the tile workshop. She resembles a grown-up version of the schoolgirl in the jeepney. She tells you that she travels to New York City every year for the Armory Show and Miami for Art Basel. She has a large extended family in the U.S., in Houston, Texas, and is worried for them given the country’s president-elect. She says that he reminds her too much of the Philippines’ own president. A showman, she says. The artisans nod their heads in agreement. One looks up from the mosaic-in-progress and shares that she too has family in the U.S., in Paramus, New Jersey. You realize for the first time during the visit at the workshop that these young women speak English, in addition to Tagalog, the language that they had used with the curator from Manila. The world seems in that moment small, in both a good and bad way. The good, a common language, the bad, the commonness of male bravado and the universality of an unfettered ego.

Curator M and Curator I, I imagine for our travels in Manila, Bataan, Singapore, Hanoi, and Ho Chi Minh City, a host of such individuals, who welcome us into their countries and cities, who through the awkwardness of the getting-to-know-you conversations and then via the vagaries and happenstances of expressed curiosities and found-connections introduce us to what we had journeyed there to see. You know, “contemporary culture.”

We take photographs of them and with them, and we annotate their names and how they connected us with the city, country, and the artists whom we met there. We, you know, remember them. How they might have joined us after our museum visits, eaten an early lunch with us—a bowl of hủ tiếu in Saigon (that is what most of its inhabitants still call it and not “Ho Chi Minh City”) because they wanted us to try something else besides the ubiquitous phở—and suggested a visit to the studio of an artist whose work is as wry, sardonic, and unexpected as she is. I imagine the artist, in her late eighties, tells us that when you are small, female, and old enough you become invisible, and then you can create in freedom. I imagine that her words send a shiver down our collective spine because we would not define freedom in such a way. I imagine her art is a rare bird.

AUTHOR BIO

Monique Truong is the Vietnamese American author of the bestselling, award-winning novels, The Book of Salt (Houghton Mifflin, 2003), Bitter in the Mouth (Random House, 2010), and the forthcoming The Sweetest Fruits (Viking Books, 2019). // monique-truong.com

Monique Truong is the Vietnamese American author of the bestselling, award-winning novels, The Book of Salt (Houghton Mifflin, 2003), Bitter in the Mouth (Random House, 2010), and the forthcoming The Sweetest Fruits (Viking Books, 2019). // monique-truong.com

This is a very good essay (I was going to say ‘nice’ essay, but it’s not nice, is it) and it is a pity the curators were too thin-skinned to publish their own critique – too long in coming and too truthful and uncomfortable to be lived with, I suppose.

I imagine the take away lesson for them will not be an altered sense of perspective or an opening of potentialities in art, culture and society but rather that next time they wont travel with someone who has such eviscerating skill with words. Brava.

This is a deeply felt essay which made me think. In contrast Pico Iyer’s is frothy and does not mention all the things Monique Truong had noticed – no names of natives – even Dayanita Singhs’ photos all lumped together.

Ms Truong’s writing is too honest and disturbing for the superficial culture elite that dominate our world. I am so very grateful to have found Diacritics which I did after hearing Viet Thanh Nguyen on a program with Ariel Dorfman on Democracy Now. I read this twice and will print it out and email it for my friends. It leads me to want to read Monique Truong’s novels which I will do when I return to ‘God’s Country’ in February 2019. I am of Indian origin and spend 4 to 5 months each year in Mumbai but have lived in the US since 1972. I wish Ms Truong and Diacritics all the VERY BEST!

With admiration and appreciation,

Bindu