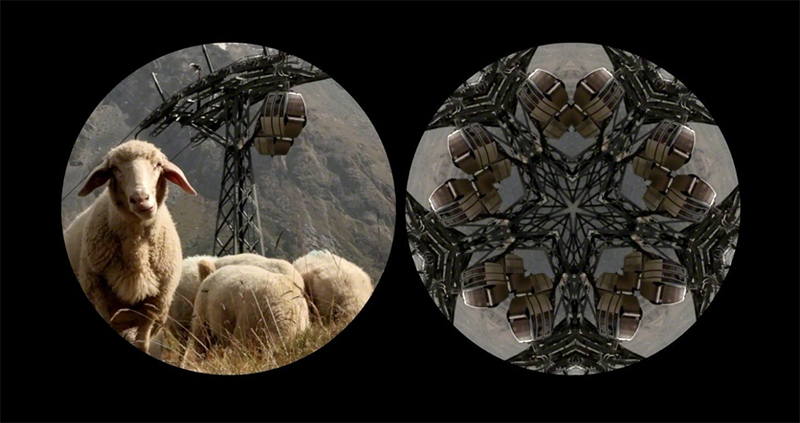

In 2014, as part of its ongoing digital art exhibition Midnight Moment, Times Square Arts ran Leslie Thornton’s Binocular Menagerie. From 11:57 PM until 12:00 AM every night in May, screens of circular videos lit up the commercial intersection. On the left, an animal would appear eating, playing, or sometimes just resting. On the right, however, the video would be manipulated into a pulsating kaleidoscope, flashing and changing with each minor movement of its animal subject.

Four years later, poet Vi Khi Nao uses Thornton’s Binocular Menagerie as a jumping point for her book-length ekphrasis Sheep Machine. Nao’s book takes its title from a particular video in Thornton’s series, also called “Sheep Machine.” Recorded in the Swiss Alps, the left side of Thornton’s video shows sheep feeding in a field while a conveyor belt of cable cars ascend and return from a mountain. The manipulated video on the right, however, becomes abstract. By juxtaposing two versions of the same video, Thornton asks us to question our assumptions about what we see: when what we see is so easily manipulated, can we truly trust our eyes? To experience Thornton’s Binocular Menagerie, one must slow down and watch—really watch. And this is what Nao sets out to do in her fifth book.

Ostensibly, Sheep Machine is a record of Nao’s watching. Each section is a one-second increment of the video, starting at 0:00 where Nao writes simply “Pitch-black.” With each passing second, Nao describes what she sees. “The grass consecrates, bending” at two seconds while at three “a sheep appears with its head down.” The act of translating image to text, though, is a tenuous task.

One can describe more universally known objects—like sheep or a cable car—by naming them. But what of the abstractions on the right-hand side of Thornton’s video? And how can these be described if they’re in a constant state of change? Nao tries her best. At four seconds, she sees “five cloud monkeys” emerging on the right binocular. The language that follows is scientific and mathematical: the cloud monkeys “materialize” and they are “sitting equidistant” in a “pentagonal window.” By the end of the second, Nao proclaims “We know appearance isn’t deceiving.” Of course, this doesn’t last for long.

What becomes clear is that Nao’s project is arduous. Each second into Thornton’s video brings about countless changes and any shift in light “reshapes the organ of perception.” By forty-five seconds, the narrator is even questioning the number of sheep in the un-manipulated video and by fifty-five second, she admits her unreliability: “We begin to question the observer, who is becoming unreliable and quick to make specious statements based on a steady, fixated study.” Sheep Machine becomes less of an act of recording than an exploration of how imagination warps our reality and how the language we use to describe what we see is insufficient. In Nao’s visioning of Thornton’s world, Yoda emerges from a mountain, a cable car is both a coffin and “Dr. Who’s second vocational home,” and “wheat and grass, if they really put their minds to it, could become animals, sheep-like and wooly.” Nao’s language is playful and tongue-in-cheek, reminiscent of her other poetic works. Reading Sheep Machine in the context of Nao’s other books, one feels a continuity, if not in theme and subject matter, than at least the words and tone. In short, Sheep Machine is very Naoesque in the best possible way.

Given the same task of recording Thornton’s “Sheep Machine,” any other poet would come up with different words, different metaphors, different imagery; indeed, there are as many ways to describe “Sheep Machine” as there are people. Nao’s Sheep Machine is one of many, infinite “Sheep Machines.”

Accuracy, though, was never Nao’s goal. Instead, Sheep Machine is a meditation on the act of seeing. Nao asks: what do we see and how do we describe it? It is a question of truth: is what I see true and can I tell you what I see truthfully? What if what we see is different from what others see? And what happens when we “experience a collapse of reality, from what we can relate to”—when what we see we can’t possibly describe because they are outside of our personal experiences, personal vocabulary? Nao, in her imaginative prose poem, prods at these questions.

That Nao writes in an increasingly visual world—one in which, like Thornton’s video, what we see can be manipulated to not reflect reality but create a falsified image—is an important distinction. As I write this review, I am also posting a photo to Instagram. I am swiping through filters, seeing which one makes it a prettier picture, a picture that will tell my story, or at least the story I want viewers to know. This is a process everyone goes through on social media. On a much larger scale, we are bombarded with Photoshopped pictures of thin models, pumped up muscle men, not a hair out of place, not a wrinkle in sight. Meanwhile, technology—particularly artificial intelligence—is quickly approaching the point of becoming threats on both national and personal levels as it is used to manipulate narratives.

What we see increasingly cannot be trusted and our way of talking about what we see becomes doubly suspicious. In an ekphrastic exercise—a book-length prose poem cum art criticism essay—Nao cautions us against what we see with our own eyes—as well as what we read and what is reported to us.

Though a difficult work—at turns experimental, self-reflexive, humorous, and philosophical—Sheep Machine might be the work that speaks the most truthfully to our current technological age. An important work if we are to think critically about the words and images we use and consume.